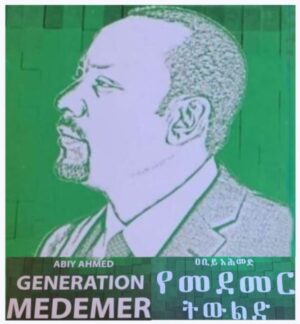

Reviewer’s Note: This is an “interpretive book review” of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s (hereinafter “Abiy”, “the author”) latest book, “Medemer Generation.” My review is not a conventional scholarly assessment of the book’s points, arguments and evidence and commentary on its hermeneutic (interpretive) value for development studies (i.e. the political economy of developing/ “Third World” countries.)

In undertaking my interpretive book review, I have at least four aims:

1) Take the analysis, arguments and evidence in the book and interpret them from my own personal perspective. I have previously reviewed the first volume in the Medemer “trilogy.” I have written numerous commentaries on the application of “Medemer” ideas to contemporary Ethiopian issues and problems. (See fn. 1, below.) I have also created an empirical equation which aims to capture the synergy element of Medemer for practical socio-political application.

The author may or may not agree with my interpretation of his ideas, analysis and arguments in the book. He may or may not agree with the direction I have taken the “Medemer” concept. The fact of the matter is that Medemer ideas are presented to the public by the author and Ethiopians are free to discuss, debate and critique them. Better yet, they ought to present their own alternatives to Medemer ideas.

2) Examine the author’s ideas and arguments critically and evaluate their validity, practicality and applicability to Ethiopia’s current problems and as a roadmap for Ethiopia’s epic struggle to achieve peace prosperity and progress in the not-too-distant future.

3) Offer my perspective on how Medemer ideas expressed by the author together with contributions, development and expansion by others could provide an ideological guide and orientation to the “Medemer Generation” that is tasked to do the heavy lifting in moving Ethiopia to its glorious destiny as “Africa’s brightest gem,” to use the poetic words of Ghana’s founding president Kwame Nkrumah.

4) Create a virtual conversation, discussion and debate among Ethiopian intellectuals on the relevance and utility of Medemer ideas to Ethiopians. Ethiopia today is the Land of Youth equally divided by gender. Seventy-six percent of the Ethiopian population is between 0-34 years. Ten percent between 35-44 years. Those above age 65 constitute 3.6 percent of the population.

Guiding my interpretive review are basic questions: What is the relevance of Medemer ideas to Ethiopia’s youth generation, the 76-86 percent that are under 35-44 years of age? How could the social, political and economic messages in the book shape or challenge the thinking of the current generation of Ethiopians? How can the ideas in the book be developed further creatively and in new directions? What better ideas can be offered as alternatives to Medemer in imagining a better and prosperous future for all Ethiopians?

I believe Ethiopian intellectuals have a moral and patriotic duty to explore and present ideas and innovations that could help the younger generation not only avoid and learn from the mistakes of past generations but also provide them constructive insights and counsel on how to do things better and more efficiently to produce a New Ethiopia that is a fair and equitable home for all its peoples.

Truth be told, I have a dim view of Ethiopian intellectuals. In my recent commentary series entitled, “A Mind is a Terrible Thing to Waste,” I issued a clarion call to Ethiopian intellectuals to stop wasting their minds; and with the fierce of urgency of now to pull back from the abyss of reactionary toxic ethnic/tribal politics and become revolutionary forces — intellectual vanguards — of national reconciliation, development and prosperity.

I have tried to be as provocative as I can in goading Ethiopian intellectuals to engage in sustained open, informed and free debate on the issues facing Ethiopia, the Horn and Africa in general. What I have seen and heard amounts to little more than gasbagging, teeth-gnashing, bellyaching and gripe sessions in an echo chamber.

Frankly, I have low expectations Ethiopian intellectuals individually or as a group will engage the author in a discussion or debate on his ideas. I believe they have collectively trapped themselves in herd/groupthink mentality and are incapable of expressing their ideas in public with the intellectual courage to brave withering criticism.

I am convinced there is no chance they will be able to offer an alternative to Medemer ideas. If I am proven wrong in my predictions, I shall publicly “eat crow,” an unpardonable blasphemy for a vegan/vegetarian.

Nonetheless, I strongly urge academics and others in the intellectual community to review, scrutinize and dissect the book for its scholarly, political and philosophical merits. Indeed, the author has thrown the gauntlet to anyone to review his book, critique it, point out its defects and improve upon it. In the alternative, he invites all to produce competing ideas that will make his own superfluous.

In my view, it takes great intellectual courage and confidence to publicly invite all to critique one’s ideas without any preconditions. In my experience, many Ethiopian intellectuals are offended by critical reviews of their books and ideas. In fact, they consider their critics mortal enemies. Here the author says, “Bring it on!”

I urge Ethiopians, especially intellectuals, to review the book, discuss, debate and comment on it, and exercise their intellectual faculties to one-up the author.

===========================================================

Structure and Organization of “Medemer Generation”

The book is organized in 3 parts and 10 chapters.

In Part One, entitled the “conception and chain of generations,” the author renders his seminal notions of “Medemer”, “generation” and “paradigm” and describes the nature, relationship and dynamics of Ethiopian generations since the mid-19th century.

In Part Two, he describes the “generations path and journey.” Here the author discusses his notions of a “generational personality and identity and advancement of generations through imaginative knowledge and ethical integrity,”

In Part Three, the author focuses on the rise of the new “Medemer Generation”. Here he discusses “Medemer” as a generation-building formula, delineates the composition, characteristic features and orientation of the new Medemer Generation. In chapter 10 of Part Three, the author presents a layered, intriguing and thought-provoking geopolitical analysis of Ethiopia and explores the opportunities and challenges facing Medemer Generation within the broader Middle Eastern context.

What is “Medemer?”

In “Medemer Generation,” the author builds upon and refines ideas he introduced in his first volume. In that volume, he presented an Ethio/Afro-centric Weltanschauung (comprehensive conception or apprehension of the world) to address the challenges of Ethiopia and the continent. That volume sought to provide direction on how to develop transformational ideas rooted in the African experience and chart a course for Ethiopia/Africa to achieve peace, prosperity and progress.

In my view, the author’s fundamental epistemological position is that Ethiopians specifically and Africans in general need to liberate themselves from the shackles of “foreign and imported ideas” which have guided their quest for “modernity.” He urges them to seek solutions by mining the rich traditions of African cultures, practices and philosophical traditions and eclectically blend them with useful foreign ideas. His analysis suggests that Africans have sought to adapt non-African ideologies with limited relevance to the African experience and superficial understanding and applied them dogmatically resulting in great harm to Ethiopia/African societies. Such blind importation and application of foreign ideas has done great damage intergenerationally by setting pernicious examples without the means and ability to correct mistakes resulting from such ideas.

Medemer, I believe, is etymologically rooted in the Amharic word “demere,” which means “gathered, put together in one, added, accumulated.” I regard Medemer as a quintessentially intellectual quest and ideological justification for the grand principle of “African/Ethiopian solutions to Africa/Ethiopian problems through dialogue, compromise and reconciliation.”

I have two perspectives on Medemer ideas.

First, “Medemer” concept/philosophy as discussed in the author’s Medemer sequels is fundamentally a system of re-imagining Ethiopian (and African societies) society in a contemporary context. It is a vision of society based on a balanced system of cooperation and competition. It completely rejects notions of division in society by class, ethnic, racial, sectarian, communal, ideological, linguistic, etc. classifications.

Second, I believe at its core “Medemer” is a critique of wholesale adoption of Western ideas be they Marxism-Leninism or liberal democracy and a proposal for an Afro/Ethio-centric ideology.

In Medemer Generation, the author defines “Medemer” as a “new framework of thought,” a mechanism “to heal our wounds and cure our ailments and resolve our problems.” He formulated his “Medemer” ideas not from philosophical investigations or speculation but from a determined practical quest for solutions to the problems faced by Ethiopia. In search of answers and perspectives, the author divulges he had to engage “diverse personalities” and deeply explore indigenous African institutions and traditions.

In a radio interview (forward clip to 13:05) in September 2019, the author explained the essence of Medemer in metaphorical terms (auth. trans.) resonating the core aspect of African humanism:

It is a lens through which we see ourselves and the world. It begins with the idea that nothing is full, there is always something lacking in individual or social life… There will always be something missing. We can meet our ever-changing needs by cooperating with and enlisting the help and support of others. So, humans must operate by balancing an existence based on cooperation and competition.

Using the “Medemer” concept, the author aims to describe socio-political “synergy” (from the Latin root “syn” (“together”) and “ergy” (“work”) in a dynamic processes of cooperation and constructive (in contrast to destructive Zero-Sum outcomes) competition. Medemer describes a synergistic process of coming together of individuals, groups, leaders and institutions to work more dynamically, effectively and creatively for the common good and in the public interest.

In my view, that synergy, using a physics metaphor, would be like fusion in which nuclei combine to release vast amounts of energy. When individuals, groups, institutions, etc. come together in “Medemer” form, they release a vast amount of social, political and economic energy.

Indeed, I formulated a quasi-physics equation to describe the synergistic process of “Medemer, which I have explained in a previous commentary.

(where Sc is social capital defined as the networks of relationships among people who live and work in a particular society; and Ac is defined as the number of active citizens involved in sustained engagement in their communities (at all levels: grassroots, civil society, villages, town, cities, nationwide activity). This equation resonates an old Ethiopian saying. “If the silk in spiders’ web could be made into twine, it could tie up a lion.”

Medemer resonates some elements of Pan-Africanism. Unlike Pan-Africanism, Medemer aims to provide a methodology to achieve the aims of strengthened bonds of solidarity among Ethiopians and African peoples for a common destiny of peace, prosperity and progress through collective (Medemer) self-reliance.

“Medemer Generation?”

In “Medemer Generation,” I understand the author arguing that change in Ethiopia has been driven by intergenerational social synergy. Medemer Generation, the one currently doing the heavy lifting in building the New Ethiopia and cultivating the generation to follow, is the product of a dialectical process of interaction of previous generations. It is the latest evolution in generational change that began in the mid-nineteenth century (with the end of the decentralized Zemene Mesafint [Era of the Princes]) but with distinctive and unique features of its own.

Several themes run throughout the book.

Social change in Ethiopia/Africa is a product of dialectical generational change in ideas, values, priorities, not “class struggle” or other violent upheavals predicted by Western ideologies/philosophies.

The necessary elements of social/political change and transformation are inherent in Ethiopian/African peoples, cultures, civilizations, hearts and minds. Non-African ideas should be eclectically adopted.

Lasting and sustainable change can come not from radical upheavals or sudden violent changes but through eclectic learning of one generation from the next and transmission of intergenerational values. The author argues, “Nation-building is a result of years of unending intergenerational exchange. A country is a result of strong linkages between generations and robust communication between them. “National success or failure is ultimately the expression of the efforts and activities of each generation in a particular “era.”

Each generation has its own “language” and way of communicating with its own members and other generations. Oftentimes, communication is lost in translation between generations resulting in gross misunderstanding and violent outcomes.

Medemer Generation’s goal is to learn from the mistakes/failures and accomplishments/successes of past generations and build a New Ethiopia that thrives in peace, prosperity and collective progress.

Medemer generation carries a historic mission of doing the heavy lifting to recreate the New Ethiopia. Medemer Generation’s way of recreating the New Ethiopia of peace, prosperity and progress is by making paradigmatic changes guided by principles of cooperation, collaboration and compromise, unity, teamwork, coalition-building, camaraderie, solidarity, tolerance, patience, resilience, steadfastness, benevolence, humanitarianism and engagement in ethical practices in all spheres of life.

Chapter 1

The author employs the concept of “generation” as Hegel uses the concept of history or Marx “class struggle” in explaining the human condition and destiny.

Hegel’s conception of history postulates a dialectal progression towards “the consciousness of freedom”. For Hegel, each generation struggles to become more and more free, until eventually a perfectly rational society of freedom is achieved.

For Abiy, the dialectical progression in Medemer is from poverty to prosperity through generational struggle. The end is not a “rational society” but a society free from want, ethnic conflict and strife, bigotry, hate, etc. Indeed, Abiy argues, “Medemer Generation” is rooted in love, fraternity and unity values.”

Abiy has a unique perspective on history, especially Ethiopian history. Unlike Hegel and Marx who are concerned with the end of history (i.e. communism for Marx and consciousness of freedom for Hegel), Abiy is concerned with the historical destiny of Ethiopia/Africa. In my analysis, Abiy’s philosophy of history revolves around generational forces (in contrast to revolutionary forces engaged in class struggle) that overlap and blend over time. It is as though these generations are in a relay race with each generation passing the baton to the next to reach the goalpost of peace, democracy, prosperity and progress.

To Abiy, human needs drive human existence. To satisfy human needs, there is competition which by itself is a source of destructive conflict. Constructive cooperation is needed to avert destructive conflict in a vicious cycle. Thus, the synergy of human needs and human cooperation produces a synthesis of prosperity (satisfaction of needs) recreating a dialectical cycle.

In my view, the author’s discussion of “Medemer” in light of the fractious nature of Ethiopian politics has a broader meaning which incorporates the idea of “synthesis” (not only synergy) or the combining of the constituent elements of separate parts into a single or unified entity.

In that sense, Medemer reflects the dynamic process of combining (adding together) disparate ideas and actions into an integrated whole. In Hegelian dialectics, ideas and actions are in a constant state of conflict and harmony. For every thesis there is anti-thesis and ultimately synthesis, repeating the cycle.

Abiy’s Medemer philosophy aims to bring synthesis to Ethiopia’s, and more broadly Africa’s, fractious politics. It aims to harmonize the politics of identity, sectarianism and communalism into a synthesis of nation-building, civility, tolerance, love, understanding and forgiveness.

Marx saw the historical process as a progression through a series of modes of production characterized by “revolutionary class struggle” unstoppably driving (historical determinism) humankind towards communism.

These distinctions are important because Abiy’s argument is significantly a critique of imported socialism of the “Dreamer Generation” (discussed below) in Ethiopia beginning in the 1960s and culminating in the distortion of the political culture and infatuation with the use of violence to bring about social and political change.

The essence of Medemer is not “class struggle” but collective cooperation and collaboration that is transmitted intergenerationally. Change does not come through the barrel of the gun. Change comes through dialogue, discourse, discussion and debate. Change comes by changing hearts and minds.

If one were to telescope Abiy’s argument, the end of history would not be liberalism/socialism triumphant but prosperity triumphant through which consciousness is achieved. In my view, the author’s conception of prosperity in Medemer context goes beyond mere economic well-being and encompasses attainment of spiritual, ethical and intellectual fulfillment for a virtuous life.

The author suggests the generational forces that have shaped and continue to shape Ethiopia’s history and destiny have faced the same challenges of struggling to ascertain their own identity and find themselves conflicted between traditional and Western (foreign) values. Ethiopia’s “modern” generations have faced problems in harmonizing Ethiopian and Western values and each generation had to struggle to master its own history and overcome its own unique challenges. To demonstrate the intergenerational interdependence, Abiy employs the metaphor of a family tree and how nations are formed “through the succession of generations that have been shaped by the prevalent thought perspective of their time.”

The author implicitly contrasts Medemer Generation with Western “generations.”

For instance, the author appreciates the legacy of America’s (West’s) “Greatest Generation” that overcame the deprivation of the Great Depression and the carnage and chaos of WW II to build an American (Western) economy that remains globally dominant to the present day.

He finds the success of the “Greatest Generation” in the fact that it was driven by strong values. He argues that generation exemplified the virtues of mutual respect, appreciated the value of cooperation, showed great commitment to family life and used military discipline and service experience (work ethic) to propel those nations to extraordinary heights.

Abiy’s concept of “generation” draws on Ethiopian culture and society. Using the Gada system as an example, he argues in Ethiopia with age comes social responsibility and roles are defined by it. In the Gada system, he finds a “generational division of labor, a governance system in which members of society assume different social and economic responsibilities as they reach different age groups.” It is a homegrown democratic system guided by elders who are elected by the community to undertake social, political and military responsibilities.

The lessons he draws from the Western generational comparisons is that each generation reacted to their specific circumstances and challenges, overcame them through resilient efforts and tried to leave a lasting legacy to generations following them. Abiy seems to suggest Medemer Generation could be “Ethiopia’s Greatest Generation” because it can build upon a system of generational practices drawing upon national pride, patriotism, values, ethics and so on.

Medemer Generation is a generational paradigm shift. The author uses the concept of “paradigm” as a “the lens through which we look at the world the framework of thought that helps us answer how the world is or should be how we understand and respond to problems.”

The author’s use of the concept of paradigm tracks Thomas Kuhn’s (who coined the term) idea that the history of science is characterized by revolutions in scientific outlook. Scientists have a worldview or a “paradigm,” a universally acknowledged scientific achievement which provides model solutions to members of a scientific community. For instance, the Ptolemaic system postulated the earth is stationary and at the center of the universe. The Copernican system revolutionized physics and astronomy and how humans understood the universe. The paradigmatic shift was that the Copernican system (based on a solar system in which the Earth and other planets moving around the Sun) revolutionized scientific thinking about the universe and provided answers the Ptolemaic system could not.

The author’s argument is that change in Ethiopia has been the cumulative effect of intergenerational paradigm shifts in thinking and practice. He argues that when monarchical system failed to answer societal and political questions it opened the way for a radical generational paradigm shift to socialism with foundational changes in land rights. “The royals and nobility did not sufficiently recognize the questions and interests of the student movement” in democracy, land reform, etc, accelerating their violent end.

The author finds changes in Japan and China instructive. The generation that emerged in Japan in the 1960s during the years of economic growth and prosperity was not exposed to the horrors of WW II and enjoyed the benefits of higher education. But economic growth and technological change chipped away at traditional Japanese family values creating a generation that placed a higher value on individualism. Successive leadership generations in China not only managed to massively reduce poverty by also placed China as an economic powerhouse. The author argues change of values and generational wisdom plays a decisive role in current and future generations. The author argues today’s China is the result of the efforts and struggles of previous generations and intergenerational transmission of wisdom in nation-building.

The nature and relationship of modern Ethiopian generations

Abiy’s understanding of generational and intergenerational dynamics in Ethiopia is noteworthy. He argues the younger generation either tends to undermine or exaggerate the legacy of previous generations. Ethiopian generations have sweepingly condemned previous generations as irredeemably backward or viewed them with romantic nostalgia mystifying and exaggerating their legacy. As an example, Abiy uses the blind adoption of Marxist ideology and its disastrous consequences on Ethiopian society, which he believes must be used as learning moments.

Another major issue he identifies is the fact that many members of the generation that advanced Marxist ideology and took direct roles in socialist revolution are still active in Ethiopian politics. He cautions against harsh condemnation of that generation because he recognizes the historical contributions they have made.

Abiy begins his analysis of generational change from the middle of the nineteenth century during the reign of Emperor Tewodros, whom he credits as the first modernizer of Ethiopia. The quest for “modernity” has been the driving force of many generations of Ethiopians. He argues the search for “modernity characterized by progressive adoption of Western modernization has led successive generations to fall under the influence what was then an alien phenomenon and lifestyle changes that introduced significant behavioral changes.”

Abiy argues, “The formation of modern generations emanates from the history of our heroes and intellectuals it is linked with the history of our ink and blood understanding our books and our history of war understanding our intellectuals and our armies is very helpful and understanding the legacy and character of various generations “

Abiy finds it perplexing that descendants of those who successfully defeated European invaders should easily fall prey and become victims of European socialist ideology, develop contempt and hatred for their own culture and have blind admiration for everything that is foreign always talking about the civilization of foreigners.

Abiy’s “taxonomic” classification of Ethiopian generations

In telescoping modern Ethiopian history, Abiy identifies four distinct and somewhat overlapping generations.

“Conservative Generation”

The Conservative Generation, imbued with the spirit of victory at Adwa in 1896, is the first to experience “modernity” (elements of Western modernization). It was the first to have access to modern schools, hotels, cars, cinemas, airplanes and newspapers. That generation placed a premium on “Ethiopianness” and strove for unity and cooperation. It sought to emulate Japan which had successfully modernized while maintaining a balance and blending its traditional values with the technological progress of Westernization. The Conservative generation sought “to preserve the culture ethos spirits and patriotism and pride of Ethiopians and aspired to harmonize the modern with the traditional values.”

“Dreamer Generation”

The Dreamer Generation came into being in the middle of the 20th century and is sometimes referred to as “the children of the 1960s.” This generation was shaped by the expansion of modern education mass media and broad exposure to foreign values and practices. The “student movement” phenomenon was unique to this generation which steeped itself in socialist ideology and organized itself in revolutionary “study clubs.” It mimicked upheavals in Western higher education. Its principal aspiration was to see a democratic Ethiopia but got caught in a vicious cycle of violence which traumatized millions and led to mass exile and displacement of hundreds of thousands. This generation was also on the receiving end of the Red and White Terror campaigns of military Derg rule (which stole this generation’s socialist thunder) in Ethiopia after the military took power. This generation found itself enamored with foreign ideas and ideologies and believed it could solve the country’s problems with European revolutionary ideology. It had little understanding or appreciation of indigenous culture. It had an exaggerated admiration for Western culture and was disconnected from the values and pride that produced victory at Adwa. The author credits the Dreamer Generation as being instrumental in bringing radical changes especially in land tenure reform.

While the Conservative Generation was willing to blend tradition with modernity, the Dreamer Generation did not find much that is worthwhile in traditional values and wanted to fully uproot the existing reality and replace it with a new socialist culture and society. “The leading intellectual figures of the time seemed to believe the solution to all our problems could be derived from the thoughts of a few foreign individuals.”

Abiy finds it incomprehensible that the Dreamer Generation could adopt and impose a “completely atheist ideology upon a deeply religious country where there was an established tradition of dialogue and deliberation to resolve problems.” The socialist revolution advocated by the leaders of this generation sought the complete annihilation of the structures and values of the people resulting in total failure.

Disillusioned Generation

The Disillusioned (confused) Generation came in last three decades of the 20th century in the aftermath of the demise of the Derg and socialism. This generation witnessed the rise of the ethno-nationalist wing of the Dreamer Generation. It is disillusioned because of the demise of socialism and ruination of its sacrifices and the political confusion that engulfed the country. Due to its traumatic experience during the Red and White Terror years, this generation lost clear content of politics and disengaged from politics.

Alienated Generation

This is the millennial generation that has been raised on the politics of division. It is estranged from other generations, ignorant of the country’s complex history and is overwhelmed by bitterness and frustration. Its alienation stems from institutionalized politics of division and globalization which has enhanced the influence of foreign social/media to sow ignorance and confusion among members of this generation.

Abiy conceives of the Alienated Generation as, what I would call, the “gimmie generation.” This generation demands what the country cannot provide and would rather migrate to foreign lands for an uncertain future than stay and strive to make things better at home. It asserts its rights but is clueless of the responsibilities attached to those rights. Its expectations are shaped by globalization. It suffers from a malaise of self-pity, hopelessness, and victimhood. It has limited critical thinking abilities and consumes disinformation on social media mindlessly. Its politics is characterized by extremism and radicalism, a lesson it learned from the Dreamer generation. It does not understand the efforts and sacrifices required to build a durable democracy…

(TO BE CONTINUED…)

=======================

Footnotes:

See e.g., “Medemer Way or “Ethiopian Solutions to Ethiopian Problems” https://almariam.com/2023/02/16/Medemer-way-or-ethiopian-solutions-to-ethiopian-problems/

“Medemer or not Medemer, That is the Question for All Ethiopians!” http://almariam.com/2018/08/26/Medemer-or-not-Medemer-that-is-the-question-for-all-ethiopians/

“The Praxis of Medemer in the Horn of Africa,” http://almariam.com/2019/03/07/the-praxis-of-Medemer-in-the-horn-of-africa/

“Medemer in America and Ethiopia: My Personal Tribute to the Life, Achievements and Legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.” http://almariam.com/2019/01/20/Medemer-in-america-and-ethiopia-my-personal-tribute-to-the-life-achievements-and-legacy-of-dr-martin-luther-king-jr/

“Ethiopia’s Youth and the Power of Medemer,” http://almariam.com/2018/10/08/author-ahmed-ethiopias-youth-and-the-power-of-Medemer/

The Power of Medemer and the “Disarming of the Ethiopia Opposition?” http://almariam.com/2019/08/11/raising-the-white-flag-the-power-of-Medemer-and-the-disarming-of-the-ethiopia-opposition/

“Medemer Generation”(MEDGEN): Tip of the Spear for Ethiopia’s Peace, Prosperity and Progress (Part I)

Posted in Al Mariam's Commentaries By almariam On April 7, 2023Reviewer’s Note: This is an “interpretive book review” of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s (hereinafter “Abiy”, “the author”) latest book, “Medemer Generation.” My review is not a conventional scholarly assessment of the book’s points, arguments and evidence and commentary on its hermeneutic (interpretive) value for development studies (i.e. the political economy of developing/ “Third World” countries.)

In undertaking my interpretive book review, I have at least four aims:

1) Take the analysis, arguments and evidence in the book and interpret them from my own personal perspective. I have previously reviewed the first volume in the Medemer “trilogy.” I have written numerous commentaries on the application of “Medemer” ideas to contemporary Ethiopian issues and problems. (See fn. 1, below.) I have also created an empirical equation which aims to capture the synergy element of Medemer for practical socio-political application.

The author may or may not agree with my interpretation of his ideas, analysis and arguments in the book. He may or may not agree with the direction I have taken the “Medemer” concept. The fact of the matter is that Medemer ideas are presented to the public by the author and Ethiopians are free to discuss, debate and critique them. Better yet, they ought to present their own alternatives to Medemer ideas.

2) Examine the author’s ideas and arguments critically and evaluate their validity, practicality and applicability to Ethiopia’s current problems and as a roadmap for Ethiopia’s epic struggle to achieve peace prosperity and progress in the not-too-distant future.

3) Offer my perspective on how Medemer ideas expressed by the author together with contributions, development and expansion by others could provide an ideological guide and orientation to the “Medemer Generation” that is tasked to do the heavy lifting in moving Ethiopia to its glorious destiny as “Africa’s brightest gem,” to use the poetic words of Ghana’s founding president Kwame Nkrumah.

4) Create a virtual conversation, discussion and debate among Ethiopian intellectuals on the relevance and utility of Medemer ideas to Ethiopians. Ethiopia today is the Land of Youth equally divided by gender. Seventy-six percent of the Ethiopian population is between 0-34 years. Ten percent between 35-44 years. Those above age 65 constitute 3.6 percent of the population.

Guiding my interpretive review are basic questions: What is the relevance of Medemer ideas to Ethiopia’s youth generation, the 76-86 percent that are under 35-44 years of age? How could the social, political and economic messages in the book shape or challenge the thinking of the current generation of Ethiopians? How can the ideas in the book be developed further creatively and in new directions? What better ideas can be offered as alternatives to Medemer in imagining a better and prosperous future for all Ethiopians?

I believe Ethiopian intellectuals have a moral and patriotic duty to explore and present ideas and innovations that could help the younger generation not only avoid and learn from the mistakes of past generations but also provide them constructive insights and counsel on how to do things better and more efficiently to produce a New Ethiopia that is a fair and equitable home for all its peoples.

Truth be told, I have a dim view of Ethiopian intellectuals. In my recent commentary series entitled, “A Mind is a Terrible Thing to Waste,” I issued a clarion call to Ethiopian intellectuals to stop wasting their minds; and with the fierce of urgency of now to pull back from the abyss of reactionary toxic ethnic/tribal politics and become revolutionary forces — intellectual vanguards — of national reconciliation, development and prosperity.

I have tried to be as provocative as I can in goading Ethiopian intellectuals to engage in sustained open, informed and free debate on the issues facing Ethiopia, the Horn and Africa in general. What I have seen and heard amounts to little more than gasbagging, teeth-gnashing, bellyaching and gripe sessions in an echo chamber.

Frankly, I have low expectations Ethiopian intellectuals individually or as a group will engage the author in a discussion or debate on his ideas. I believe they have collectively trapped themselves in herd/groupthink mentality and are incapable of expressing their ideas in public with the intellectual courage to brave withering criticism.

I am convinced there is no chance they will be able to offer an alternative to Medemer ideas. If I am proven wrong in my predictions, I shall publicly “eat crow,” an unpardonable blasphemy for a vegan/vegetarian.

Nonetheless, I strongly urge academics and others in the intellectual community to review, scrutinize and dissect the book for its scholarly, political and philosophical merits. Indeed, the author has thrown the gauntlet to anyone to review his book, critique it, point out its defects and improve upon it. In the alternative, he invites all to produce competing ideas that will make his own superfluous.

In my view, it takes great intellectual courage and confidence to publicly invite all to critique one’s ideas without any preconditions. In my experience, many Ethiopian intellectuals are offended by critical reviews of their books and ideas. In fact, they consider their critics mortal enemies. Here the author says, “Bring it on!”

I urge Ethiopians, especially intellectuals, to review the book, discuss, debate and comment on it, and exercise their intellectual faculties to one-up the author.

===========================================================

Structure and Organization of “Medemer Generation”

The book is organized in 3 parts and 10 chapters.

In Part One, entitled the “conception and chain of generations,” the author renders his seminal notions of “Medemer”, “generation” and “paradigm” and describes the nature, relationship and dynamics of Ethiopian generations since the mid-19th century.

In Part Two, he describes the “generations path and journey.” Here the author discusses his notions of a “generational personality and identity and advancement of generations through imaginative knowledge and ethical integrity,”

In Part Three, the author focuses on the rise of the new “Medemer Generation”. Here he discusses “Medemer” as a generation-building formula, delineates the composition, characteristic features and orientation of the new Medemer Generation. In chapter 10 of Part Three, the author presents a layered, intriguing and thought-provoking geopolitical analysis of Ethiopia and explores the opportunities and challenges facing Medemer Generation within the broader Middle Eastern context.

What is “Medemer?”

In “Medemer Generation,” the author builds upon and refines ideas he introduced in his first volume. In that volume, he presented an Ethio/Afro-centric Weltanschauung (comprehensive conception or apprehension of the world) to address the challenges of Ethiopia and the continent. That volume sought to provide direction on how to develop transformational ideas rooted in the African experience and chart a course for Ethiopia/Africa to achieve peace, prosperity and progress.

In my view, the author’s fundamental epistemological position is that Ethiopians specifically and Africans in general need to liberate themselves from the shackles of “foreign and imported ideas” which have guided their quest for “modernity.” He urges them to seek solutions by mining the rich traditions of African cultures, practices and philosophical traditions and eclectically blend them with useful foreign ideas. His analysis suggests that Africans have sought to adapt non-African ideologies with limited relevance to the African experience and superficial understanding and applied them dogmatically resulting in great harm to Ethiopia/African societies. Such blind importation and application of foreign ideas has done great damage intergenerationally by setting pernicious examples without the means and ability to correct mistakes resulting from such ideas.

Medemer, I believe, is etymologically rooted in the Amharic word “demere,” which means “gathered, put together in one, added, accumulated.” I regard Medemer as a quintessentially intellectual quest and ideological justification for the grand principle of “African/Ethiopian solutions to Africa/Ethiopian problems through dialogue, compromise and reconciliation.”

I have two perspectives on Medemer ideas.

First, “Medemer” concept/philosophy as discussed in the author’s Medemer sequels is fundamentally a system of re-imagining Ethiopian (and African societies) society in a contemporary context. It is a vision of society based on a balanced system of cooperation and competition. It completely rejects notions of division in society by class, ethnic, racial, sectarian, communal, ideological, linguistic, etc. classifications.

Second, I believe at its core “Medemer” is a critique of wholesale adoption of Western ideas be they Marxism-Leninism or liberal democracy and a proposal for an Afro/Ethio-centric ideology.

In Medemer Generation, the author defines “Medemer” as a “new framework of thought,” a mechanism “to heal our wounds and cure our ailments and resolve our problems.” He formulated his “Medemer” ideas not from philosophical investigations or speculation but from a determined practical quest for solutions to the problems faced by Ethiopia. In search of answers and perspectives, the author divulges he had to engage “diverse personalities” and deeply explore indigenous African institutions and traditions.

In a radio interview (forward clip to 13:05) in September 2019, the author explained the essence of Medemer in metaphorical terms (auth. trans.) resonating the core aspect of African humanism:

Using the “Medemer” concept, the author aims to describe socio-political “synergy” (from the Latin root “syn” (“together”) and “ergy” (“work”) in a dynamic processes of cooperation and constructive (in contrast to destructive Zero-Sum outcomes) competition. Medemer describes a synergistic process of coming together of individuals, groups, leaders and institutions to work more dynamically, effectively and creatively for the common good and in the public interest.

In my view, that synergy, using a physics metaphor, would be like fusion in which nuclei combine to release vast amounts of energy. When individuals, groups, institutions, etc. come together in “Medemer” form, they release a vast amount of social, political and economic energy.

Indeed, I formulated a quasi-physics equation to describe the synergistic process of “Medemer, which I have explained in a previous commentary.

(where Sc is social capital defined as the networks of relationships among people who live and work in a particular society; and Ac is defined as the number of active citizens involved in sustained engagement in their communities (at all levels: grassroots, civil society, villages, town, cities, nationwide activity). This equation resonates an old Ethiopian saying. “If the silk in spiders’ web could be made into twine, it could tie up a lion.”

Medemer resonates some elements of Pan-Africanism. Unlike Pan-Africanism, Medemer aims to provide a methodology to achieve the aims of strengthened bonds of solidarity among Ethiopians and African peoples for a common destiny of peace, prosperity and progress through collective (Medemer) self-reliance.

“Medemer Generation?”

In “Medemer Generation,” I understand the author arguing that change in Ethiopia has been driven by intergenerational social synergy. Medemer Generation, the one currently doing the heavy lifting in building the New Ethiopia and cultivating the generation to follow, is the product of a dialectical process of interaction of previous generations. It is the latest evolution in generational change that began in the mid-nineteenth century (with the end of the decentralized Zemene Mesafint [Era of the Princes]) but with distinctive and unique features of its own.

Several themes run throughout the book.

Social change in Ethiopia/Africa is a product of dialectical generational change in ideas, values, priorities, not “class struggle” or other violent upheavals predicted by Western ideologies/philosophies.

The necessary elements of social/political change and transformation are inherent in Ethiopian/African peoples, cultures, civilizations, hearts and minds. Non-African ideas should be eclectically adopted.

Lasting and sustainable change can come not from radical upheavals or sudden violent changes but through eclectic learning of one generation from the next and transmission of intergenerational values. The author argues, “Nation-building is a result of years of unending intergenerational exchange. A country is a result of strong linkages between generations and robust communication between them. “National success or failure is ultimately the expression of the efforts and activities of each generation in a particular “era.”

Each generation has its own “language” and way of communicating with its own members and other generations. Oftentimes, communication is lost in translation between generations resulting in gross misunderstanding and violent outcomes.

Medemer Generation’s goal is to learn from the mistakes/failures and accomplishments/successes of past generations and build a New Ethiopia that thrives in peace, prosperity and collective progress.

Medemer generation carries a historic mission of doing the heavy lifting to recreate the New Ethiopia. Medemer Generation’s way of recreating the New Ethiopia of peace, prosperity and progress is by making paradigmatic changes guided by principles of cooperation, collaboration and compromise, unity, teamwork, coalition-building, camaraderie, solidarity, tolerance, patience, resilience, steadfastness, benevolence, humanitarianism and engagement in ethical practices in all spheres of life.

Chapter 1

The author employs the concept of “generation” as Hegel uses the concept of history or Marx “class struggle” in explaining the human condition and destiny.

Hegel’s conception of history postulates a dialectal progression towards “the consciousness of freedom”. For Hegel, each generation struggles to become more and more free, until eventually a perfectly rational society of freedom is achieved.

For Abiy, the dialectical progression in Medemer is from poverty to prosperity through generational struggle. The end is not a “rational society” but a society free from want, ethnic conflict and strife, bigotry, hate, etc. Indeed, Abiy argues, “Medemer Generation” is rooted in love, fraternity and unity values.”

Abiy has a unique perspective on history, especially Ethiopian history. Unlike Hegel and Marx who are concerned with the end of history (i.e. communism for Marx and consciousness of freedom for Hegel), Abiy is concerned with the historical destiny of Ethiopia/Africa. In my analysis, Abiy’s philosophy of history revolves around generational forces (in contrast to revolutionary forces engaged in class struggle) that overlap and blend over time. It is as though these generations are in a relay race with each generation passing the baton to the next to reach the goalpost of peace, democracy, prosperity and progress.

To Abiy, human needs drive human existence. To satisfy human needs, there is competition which by itself is a source of destructive conflict. Constructive cooperation is needed to avert destructive conflict in a vicious cycle. Thus, the synergy of human needs and human cooperation produces a synthesis of prosperity (satisfaction of needs) recreating a dialectical cycle.

In my view, the author’s discussion of “Medemer” in light of the fractious nature of Ethiopian politics has a broader meaning which incorporates the idea of “synthesis” (not only synergy) or the combining of the constituent elements of separate parts into a single or unified entity.

In that sense, Medemer reflects the dynamic process of combining (adding together) disparate ideas and actions into an integrated whole. In Hegelian dialectics, ideas and actions are in a constant state of conflict and harmony. For every thesis there is anti-thesis and ultimately synthesis, repeating the cycle.

Abiy’s Medemer philosophy aims to bring synthesis to Ethiopia’s, and more broadly Africa’s, fractious politics. It aims to harmonize the politics of identity, sectarianism and communalism into a synthesis of nation-building, civility, tolerance, love, understanding and forgiveness.

Marx saw the historical process as a progression through a series of modes of production characterized by “revolutionary class struggle” unstoppably driving (historical determinism) humankind towards communism.

These distinctions are important because Abiy’s argument is significantly a critique of imported socialism of the “Dreamer Generation” (discussed below) in Ethiopia beginning in the 1960s and culminating in the distortion of the political culture and infatuation with the use of violence to bring about social and political change.

The essence of Medemer is not “class struggle” but collective cooperation and collaboration that is transmitted intergenerationally. Change does not come through the barrel of the gun. Change comes through dialogue, discourse, discussion and debate. Change comes by changing hearts and minds.

If one were to telescope Abiy’s argument, the end of history would not be liberalism/socialism triumphant but prosperity triumphant through which consciousness is achieved. In my view, the author’s conception of prosperity in Medemer context goes beyond mere economic well-being and encompasses attainment of spiritual, ethical and intellectual fulfillment for a virtuous life.

The author suggests the generational forces that have shaped and continue to shape Ethiopia’s history and destiny have faced the same challenges of struggling to ascertain their own identity and find themselves conflicted between traditional and Western (foreign) values. Ethiopia’s “modern” generations have faced problems in harmonizing Ethiopian and Western values and each generation had to struggle to master its own history and overcome its own unique challenges. To demonstrate the intergenerational interdependence, Abiy employs the metaphor of a family tree and how nations are formed “through the succession of generations that have been shaped by the prevalent thought perspective of their time.”

The author implicitly contrasts Medemer Generation with Western “generations.”

For instance, the author appreciates the legacy of America’s (West’s) “Greatest Generation” that overcame the deprivation of the Great Depression and the carnage and chaos of WW II to build an American (Western) economy that remains globally dominant to the present day.

He finds the success of the “Greatest Generation” in the fact that it was driven by strong values. He argues that generation exemplified the virtues of mutual respect, appreciated the value of cooperation, showed great commitment to family life and used military discipline and service experience (work ethic) to propel those nations to extraordinary heights.

Abiy’s concept of “generation” draws on Ethiopian culture and society. Using the Gada system as an example, he argues in Ethiopia with age comes social responsibility and roles are defined by it. In the Gada system, he finds a “generational division of labor, a governance system in which members of society assume different social and economic responsibilities as they reach different age groups.” It is a homegrown democratic system guided by elders who are elected by the community to undertake social, political and military responsibilities.

The lessons he draws from the Western generational comparisons is that each generation reacted to their specific circumstances and challenges, overcame them through resilient efforts and tried to leave a lasting legacy to generations following them. Abiy seems to suggest Medemer Generation could be “Ethiopia’s Greatest Generation” because it can build upon a system of generational practices drawing upon national pride, patriotism, values, ethics and so on.

Medemer Generation is a generational paradigm shift. The author uses the concept of “paradigm” as a “the lens through which we look at the world the framework of thought that helps us answer how the world is or should be how we understand and respond to problems.”

The author’s use of the concept of paradigm tracks Thomas Kuhn’s (who coined the term) idea that the history of science is characterized by revolutions in scientific outlook. Scientists have a worldview or a “paradigm,” a universally acknowledged scientific achievement which provides model solutions to members of a scientific community. For instance, the Ptolemaic system postulated the earth is stationary and at the center of the universe. The Copernican system revolutionized physics and astronomy and how humans understood the universe. The paradigmatic shift was that the Copernican system (based on a solar system in which the Earth and other planets moving around the Sun) revolutionized scientific thinking about the universe and provided answers the Ptolemaic system could not.

The author’s argument is that change in Ethiopia has been the cumulative effect of intergenerational paradigm shifts in thinking and practice. He argues that when monarchical system failed to answer societal and political questions it opened the way for a radical generational paradigm shift to socialism with foundational changes in land rights. “The royals and nobility did not sufficiently recognize the questions and interests of the student movement” in democracy, land reform, etc, accelerating their violent end.

The author finds changes in Japan and China instructive. The generation that emerged in Japan in the 1960s during the years of economic growth and prosperity was not exposed to the horrors of WW II and enjoyed the benefits of higher education. But economic growth and technological change chipped away at traditional Japanese family values creating a generation that placed a higher value on individualism. Successive leadership generations in China not only managed to massively reduce poverty by also placed China as an economic powerhouse. The author argues change of values and generational wisdom plays a decisive role in current and future generations. The author argues today’s China is the result of the efforts and struggles of previous generations and intergenerational transmission of wisdom in nation-building.

The nature and relationship of modern Ethiopian generations

Abiy’s understanding of generational and intergenerational dynamics in Ethiopia is noteworthy. He argues the younger generation either tends to undermine or exaggerate the legacy of previous generations. Ethiopian generations have sweepingly condemned previous generations as irredeemably backward or viewed them with romantic nostalgia mystifying and exaggerating their legacy. As an example, Abiy uses the blind adoption of Marxist ideology and its disastrous consequences on Ethiopian society, which he believes must be used as learning moments.

Another major issue he identifies is the fact that many members of the generation that advanced Marxist ideology and took direct roles in socialist revolution are still active in Ethiopian politics. He cautions against harsh condemnation of that generation because he recognizes the historical contributions they have made.

Abiy begins his analysis of generational change from the middle of the nineteenth century during the reign of Emperor Tewodros, whom he credits as the first modernizer of Ethiopia. The quest for “modernity” has been the driving force of many generations of Ethiopians. He argues the search for “modernity characterized by progressive adoption of Western modernization has led successive generations to fall under the influence what was then an alien phenomenon and lifestyle changes that introduced significant behavioral changes.”

Abiy argues, “The formation of modern generations emanates from the history of our heroes and intellectuals it is linked with the history of our ink and blood understanding our books and our history of war understanding our intellectuals and our armies is very helpful and understanding the legacy and character of various generations “

Abiy finds it perplexing that descendants of those who successfully defeated European invaders should easily fall prey and become victims of European socialist ideology, develop contempt and hatred for their own culture and have blind admiration for everything that is foreign always talking about the civilization of foreigners.

Abiy’s “taxonomic” classification of Ethiopian generations

In telescoping modern Ethiopian history, Abiy identifies four distinct and somewhat overlapping generations.

“Conservative Generation”

The Conservative Generation, imbued with the spirit of victory at Adwa in 1896, is the first to experience “modernity” (elements of Western modernization). It was the first to have access to modern schools, hotels, cars, cinemas, airplanes and newspapers. That generation placed a premium on “Ethiopianness” and strove for unity and cooperation. It sought to emulate Japan which had successfully modernized while maintaining a balance and blending its traditional values with the technological progress of Westernization. The Conservative generation sought “to preserve the culture ethos spirits and patriotism and pride of Ethiopians and aspired to harmonize the modern with the traditional values.”

“Dreamer Generation”

The Dreamer Generation came into being in the middle of the 20th century and is sometimes referred to as “the children of the 1960s.” This generation was shaped by the expansion of modern education mass media and broad exposure to foreign values and practices. The “student movement” phenomenon was unique to this generation which steeped itself in socialist ideology and organized itself in revolutionary “study clubs.” It mimicked upheavals in Western higher education. Its principal aspiration was to see a democratic Ethiopia but got caught in a vicious cycle of violence which traumatized millions and led to mass exile and displacement of hundreds of thousands. This generation was also on the receiving end of the Red and White Terror campaigns of military Derg rule (which stole this generation’s socialist thunder) in Ethiopia after the military took power. This generation found itself enamored with foreign ideas and ideologies and believed it could solve the country’s problems with European revolutionary ideology. It had little understanding or appreciation of indigenous culture. It had an exaggerated admiration for Western culture and was disconnected from the values and pride that produced victory at Adwa. The author credits the Dreamer Generation as being instrumental in bringing radical changes especially in land tenure reform.

While the Conservative Generation was willing to blend tradition with modernity, the Dreamer Generation did not find much that is worthwhile in traditional values and wanted to fully uproot the existing reality and replace it with a new socialist culture and society. “The leading intellectual figures of the time seemed to believe the solution to all our problems could be derived from the thoughts of a few foreign individuals.”

Abiy finds it incomprehensible that the Dreamer Generation could adopt and impose a “completely atheist ideology upon a deeply religious country where there was an established tradition of dialogue and deliberation to resolve problems.” The socialist revolution advocated by the leaders of this generation sought the complete annihilation of the structures and values of the people resulting in total failure.

Disillusioned Generation

The Disillusioned (confused) Generation came in last three decades of the 20th century in the aftermath of the demise of the Derg and socialism. This generation witnessed the rise of the ethno-nationalist wing of the Dreamer Generation. It is disillusioned because of the demise of socialism and ruination of its sacrifices and the political confusion that engulfed the country. Due to its traumatic experience during the Red and White Terror years, this generation lost clear content of politics and disengaged from politics.

Alienated Generation

This is the millennial generation that has been raised on the politics of division. It is estranged from other generations, ignorant of the country’s complex history and is overwhelmed by bitterness and frustration. Its alienation stems from institutionalized politics of division and globalization which has enhanced the influence of foreign social/media to sow ignorance and confusion among members of this generation.

Abiy conceives of the Alienated Generation as, what I would call, the “gimmie generation.” This generation demands what the country cannot provide and would rather migrate to foreign lands for an uncertain future than stay and strive to make things better at home. It asserts its rights but is clueless of the responsibilities attached to those rights. Its expectations are shaped by globalization. It suffers from a malaise of self-pity, hopelessness, and victimhood. It has limited critical thinking abilities and consumes disinformation on social media mindlessly. Its politics is characterized by extremism and radicalism, a lesson it learned from the Dreamer generation. It does not understand the efforts and sacrifices required to build a durable democracy…

(TO BE CONTINUED…)

=======================

Footnotes:

See e.g., “Medemer Way or “Ethiopian Solutions to Ethiopian Problems” https://almariam.com/2023/02/16/Medemer-way-or-ethiopian-solutions-to-ethiopian-problems/

“Medemer or not Medemer, That is the Question for All Ethiopians!” http://almariam.com/2018/08/26/Medemer-or-not-Medemer-that-is-the-question-for-all-ethiopians/

“The Praxis of Medemer in the Horn of Africa,” http://almariam.com/2019/03/07/the-praxis-of-Medemer-in-the-horn-of-africa/

“Medemer in America and Ethiopia: My Personal Tribute to the Life, Achievements and Legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.” http://almariam.com/2019/01/20/Medemer-in-america-and-ethiopia-my-personal-tribute-to-the-life-achievements-and-legacy-of-dr-martin-luther-king-jr/

“Ethiopia’s Youth and the Power of Medemer,” http://almariam.com/2018/10/08/author-ahmed-ethiopias-youth-and-the-power-of-Medemer/

The Power of Medemer and the “Disarming of the Ethiopia Opposition?” http://almariam.com/2019/08/11/raising-the-white-flag-the-power-of-Medemer-and-the-disarming-of-the-ethiopia-opposition/

Share this:

Related Posts