In the interest of full disclosure, I have a special place in my heart for Nelson Mandela and South Africa.

That is understandable because Mandela in his autobiography, “The Long Walk to Freedom” wrote:

Ethiopia always has a special place in my imagination and the prospect of visiting Ethiopia attracted me more strongly than a trip to France, England, and America combined. I felt I would be visiting my own genesis, unearthing the roots of what made me an African.

Mandela’s passing in December 2013 was a personal loss for me.

In his memory, I wrote a commentary entitled, “Farewell, My African Prince”.

Mandela was a bridge builder. He built bridges across racial, ethnic and class divides. He was a fireman. He saved the South African house by dousing the smoldering embers of racial and ethnic strife with truth and reconciliation. Nelson Mandela was a pathfinder. He built two roads named Goodness and Reconciliation for the long walk to freedom and walked the talk.

For years, I have written commentaries in remembrance of the Sharpeville Massacre.

Lately, South Africa has become ground zero for xenophobia in Africa. Accusatory fingers are demonizing of South Africans of being virulently xenophobic against African immigrants in their midst.

That is painful for me because during the anti-apartheid struggle Africans throughout the continent gave shelter to exiled South African freedom fighters and African governments provided material and diplomatic support.

H.I.M. Haile Selassie in his 1963 speech said without peace in Southern Africa, there will be no peace in Africa:

Until the philosophy that holds one race superior and another inferior is finally and permanently discredited and abandoned, the dream of lasting peace will remain but a fleeting illusion. Until the ignoble and unhappy regimes that hold our brothers in Angola, in Mozambique and South Africa in subhuman bondage have been toppled and destroyed the African continent will not know peace.

As a college student in the mid-1970s, I was a passionate anti-apartheid advocate, joined demonstrations pushing disinvestment in apartheid South Africa and opposed the so-called Sullivan Principles and constructive engagement.

Our mantra I remember to this day: “Hey, ho ho, apartheid has got to go! Brick by brick, wall by wall, apartheid has to fall!”

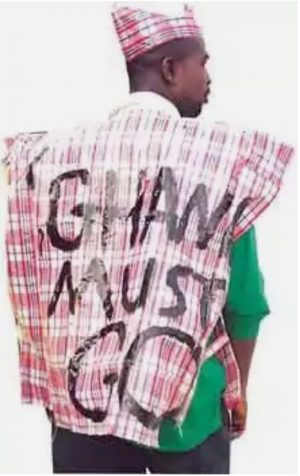

To see and hear some South Africans today looting and burning while chanting “Hey, ho, ho, African immigrant must go!” breaks my heart.

Since the advent of majority rule in 1994, many Africans who took a long walk to freedom from their countries to escape political persecution or seek economic opportunity have faced violence, intimidation and persecution in South Africa.

When an outbreak of xenophobic violence occurred in South of Africa earlier this month, 12 “foreign nationals” were confirmed dead and 639 suspects were reportedly arrested. Some 1,000 “foreign-owned” businesses were damaged or destroyed.

Violence against foreign-nationals in South Africa has been taking place since 1994.

Incidents of xenophobic violence in South Africa are well-documented.

In 1998, three “foreign nationals” were thrown out of a moving train between Johannesburg and Pretoria because they were accused of “bringing diseases, taking jobs, the same rhetoric we hear today.”

According to a 1998 Human Rights Watch report, “armed gangs of black South Africans attacked foreign nationals from Malawi, Zimbabwe and Mozambique living in the Alexandra township near Johannesburg for several weeks in 1995 in a drive to ‘clean the township of foreigners’”.

In an outbreak of xenophobic violence in 2008, at least 62 people, including South Africans, were killed, thousands were displaced and many businesses and stores owned by “foreign nationals” were looted and destroyed.

Much of the xenophobic violence is directed at “foreign nationals” operating small shops and stores in the townships or settlements around them.

Most of the violent attacks have been carried out by black South Africans.

Most of the incidents have taken place in areas experiencing high levels of poverty, unemployment and low levels of social, community and public safety services.

Foreign nationals in these areas are particularly disadvantaged because of language problems, ignorance and fear of reporting crimes to police authorities and inability to access the justice system.

The South African government has long denied the existence of xenophobic attacks.

In 2008, former president Thabo Mbeki declared South Africans are not xenophobic but foreign nationals have been victims of “naked criminal activity”. Mbeki claimed, “There isn’t a population of South Africans who attack other Africans simply because of their nationality.”

In 2015, his successor Jacob Zuma repeated the disclaimer stating, “South Africans are not xenophobic. We do not believe that the actions of a few out of more than 50 million citizens justify the label of xenophobia.”

Current president Cyril Ramaphosa has acknowledged the violence is driven by xenophobia and in a statement “condemned violence against foreign nationals in South Africa” and argued “African development depends on the increased movement of people, goods and services between different countries for all of us to benefit.”

Ramaphosa offered “profuse apologies” to Nigeria. “The incident does not represent what we stand for and the South African police leave no stone unturned, that those involved must be brought to book”.

The one South Africa leader who has not minced words about xenophobic violence is the colorful firebrand leader of Economic Freedom Fighters Party, Julius Malema.

In March 2019, Malema offered his explanation for xenophobia in South Africa:

You say the people from Nigeria and Zimbabwe are taking our jobs. But here are whites in South Africa who don’t have papers. They entered here legally. The Chinese, some of them do not have papers. You don’t call them Amakwerekwere. You don’t beat them up but you beat fellow Africans, why? You hate yourself.

Once you are done with Nigerians, Mozambicans, Zimbabweans, Zambians, you are going to go for Shangaans from Giyani. I have to stop you now before you come for me. We are going to be victims. ‘They’re going to say, ‘The reason we don’t have jobs here is because of these Zulus. They must go back to Natal. Xhosas must go back to Eastern Cape, Shangaans must go back to Limpopo.’ Because there will be no foreigners left to fight.”

His remedial prescription is simple:

We are all Africans. We must love one another. Showing love to those who come from Mozambique, showing love to those who come from Guinea, from Egypt, from Nigeria is self-love. When you love yourself, you will love fellow South Africans.

For the most recent xenophobic violence earlier this month, Malema apologized:

Find it in your good hearts to forgive us, we are sorry, we are ashamed of ourselves and sincerely apologise for this madness.

Is there rampant xenophobia in South Africa?

Independent surveys on xenophobia in South Africa point to an endemic problem.

The most comprehensive study on xenophobia in South Africa is found in a 2016 doctoral dissertation.

Several opinion surveys over the past two decades have shown South Africans have low levels of tolerance of immigration or immigrants.

“A 1997 survey showed that just six percent of South Africans were tolerant to immigration. In another survey, 75 percent of South Africans held negative perceptions about black African foreigners.”

“A 2004 study by the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation (CSVR) of attitudes among police officers in the Johannesburg area found that 87% of respondents believed most undocumented immigrants in Johannesburg are involved in crime, despite there being no statistical evidence to substantiate the perception.”

“A national survey of the attitudes of the South African population towards foreign nationals in the country by the South African Migration Project in 2006 found xenophobia to be widespread: South Africans do not want it to be easier for foreign nationals to trade informally with South Africa (59 percent opposed), to start small businesses in South Africa (61 percent opposed) or to obtain South African citizenship (68 percent opposed).”

“A 2012 independent survey showed Distrust of foreigners has increased in South Africa in the four years since a wave of xenophobic violence swept the country. Some 67 percent of South Africans say they do not trust foreigners at all, compared to 60 percent in 2008. Nearly a third of the 2,400 respondents would take action to prevent migrants from moving into their neighbourhood and 36 percent would try to stop them from operating businesses. Forty-four percent were opposed to their country providing protection to asylum seekers. 45 percent saying foreigners should not be allowed to live in the country because they take jobs and benefits away from South Africans.”

Holier-than-thou South Africa?

The old saw it true. “Remember, when you point a finger at someone, there are three more fingers pointing at you.”

Since all eyes are on South Africa today, it is appropriate to ask whether xenophobia is a “mental disease” that afflicts only South Africans.

I should like to argue xenophobia and ethnophobia afflict all African countries to varying degrees.

In the not-too-distant past, there have been instances of xenophobic violence and discrimination against “foreign nationals” in Nigeria, Ghana, Cote d’Ivoire, South Sudan, Botswana, Angola and Zambia.

When global oil prices collapsed in 1983, Nigeria ordered the massive expulsion of illegal Ghanaian migrants working in the country. The argument then is not much different than what the South Africans are saying today. Ghanaians were accused of taking jobs from Nigerians and depressing the labor market.

In 2001, Cote d’Ivoire, home to large numbers of West Africans representing more than a quarter of the population, was accused of failing to curb the growth of xenophobia.

In 2006, the Government of Niger “ordered the expulsion of 150,000 Arab refugees from Chad and neighboring countries who have lived in this West African nation for decades.”

In 2010, concerns were expressed about the rise of “extensive” xenophobic attitudes towards Zimbabweans by Botswanans.

In 2013, there were serious concerns of xenophobia in South Sudan, Africa’s newest state.

In 2017, in an act of reprisal for an alleged murder, Ghanaians attacked and killed 5 Nigerians.

In 2018, Angola denied the occurrence of xenophobic violence against Congolese migrant workers.

In 1998, following the war between Ethiopia and Eritrea, the government of the Tigrean People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) in Ethiopia undertook a mass expulsion of 20 thousand people alleged to be of Eritrean national origin.

TPLF Prime Minister Meles Zenawi at the time justified his arbitrary expulsion claiming “As long as any foreign national, whether Eritrean or Japanese etc . . . lives in Ethiopia [it is] because of the goodwill of the Ethiopian government. If we say ‘Go, because we do not like the colour of your eyes,’ they have to leave.”

There is no better example of xenophobia that deporting a person because of the color of his eyes or national origin.

Xenophobes and criminals?

Xenophobia (Greek xeno “stranger”, phobia “fear”) is not a crime. It is the “irrational, pathological fear or distrust of strangers”. Often, it manifests itself in acts of hostility, violence and discrimination against foreigners.

Are the South Africans who committed the acts of violence against other African “foreign nationals” xenophobes and/or hooligans/criminals?

The survey evidence is clear that xenophobia is a problem in South Africa, but I believe the infinitesimally small number of individuals who commit acts of violence, intimidation and looting are criminals, thugs, gangsters and hooligans.

I cannot believe the mainstream opinion of South Africans supports violent criminal activity against foreigners or others.

But I am not surprised to see anti-immigrant sentiment and violence in a nation where the unemployment rate is nearly 30 percent.

I believe many of the violent acts are committed by poor unemployed youth who have joined either criminal gangs or engage in crimes of opportunity.

Burning immigrants alive, looting and rioting will not create more jobs in South Africa. It will certainly drive away investors and tourists who could be sources of employment.

Foreign nationals are easy victims in South Africa because they have neither a voice nor representation in government and society.

The failure of the South African national government to take effective preventive and prosecutorial action against such criminals is deplorable.

Ethnophobia in Ethiopia

If xenophobia is the “irrational fear or distrust of strangers”, ethnophobia is the irrational fear and hatred of any ethnicity different to one’s own.

In 2018, Ethiopia topped the “global list of highest internal displacement”, according to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Center.

Internal displacement in Ethiopia has been fully documented and has multiple causes. “High levels of vulnerability among rural populations exposed to severe drought and floods, political and resource-based conflict and overstretched government capacity create a high-risk environment in which significant new displacements take place each year.”

However, the principal reason for internal displacement in Ethiopia, in my view, is the structure of internal colonialism created by the TPLF in the ethnic Kilil-istans (similar to South Africa’s Bantustans) which singularly accentuate and exploit ethnic and cultural differences in the country creating conflict and strife.

For instance, the dispute between the Oromia and Somali kilils (regions) resulted in the displacement of hundreds of thousands of people is the outcome of Kililistan politics.

Over 100,000 people fled ethnic violence and became internally displaced persons in Benishangul Gumuz in Western Ethiopia for the same reason.

However, the government of PM Abiy Ahmed effectively implemented an IDP return program in May 2019 “following the announcement of the Federal Government’s Strategic Plan to Address Internal Displacement and a costed Re-covery/Rehabilitation Plan. By the end of May, most IDP sites/camps were dismantled, in East/West Wollega and Gedeo/West Guji zones.”

It is interesting to note that those who howled and growled about internal displacement in Ethiopia suddenly fell silent when the government of PM Abiy Ahmed returned the displaced persons to their places of origin.

For the past 27 years, the regime of the TPLF has exploited and manipulated the political situation in Ethiopia to maintain itself in power.

Using the kilil system, the TPLF has poisoned the interaction between and among ethnic groups, cultures, traditions, religions and sown ethnic and political misunderstanding, mistrust, unrest and conflict.

Today, the legacy of 27 years of ethnophobic propaganda by the TPLF and the fear, suspicion, intolerance, disinformation and false grievances that are perpetuated by empty barrel pseudo-intellectuals and hordes of social media ignoramuses continue to be a source of aggravation and anxiety.

Xenophobia in South Africa and ethnophobia in Ethiopia are products of racial/ethnic apartheid

Apartheid a virulent form and vestige of European colonialism.

In 1948, the minority white National Party (NP) introduced “apartheid” (“apartness”) as an ideology for the separate development of the various racial groups in South Africa.

NP prime minister Hendrik Verwoerd transformed apartheid into a full-fledged de jure separate development system with the passage of the Promotion of Bantu Self Government Act of 1959 creating 10 Bantu black homelands known as Bantustans.

The central aim of this Act was to fragment and separate black South Africans into small groups so that there would be no black majority aspiring or competing for power, and to make it impossible for them to unify under a single national organization. The Act also aimed to psychologically isolate the black majority while simultaneously de-nationalizing them and depriving them of a common identity.

Strictly enforcing the passbook laws, promoting trial consciousness and using a strategy of divide and rule, the minority white apartheid regime for over four decades succeeded in creating a society riven by ethnic, tribal, religious and regional divisions in South Africa.

Following the apartheid South African model, the TPLF regime created 9 kilils (kililistans or ethnic homelands) and two “chartered cities” in Ethiopia to geographically dismember and fragment regions while establishing a hegemonic regime of ethnic supremacy.

Put simply, the TPLF regime copied the racial apartheid system of South Africa to create an ethnic-based system of internal colonialism.

I have also discussed the Bantustanization (Kililistanization) of Ethiopia in a previous commentary at length.

Suffice it to say that for 27 years, the TPLF’s internal colonialism succeeded through a systematic campaign of de-Ethiopianization similar to the way the colonial masters de-nationalized the people in their African colonies, created artificial ethnic and other boundaries (kilil homelands) and imposed their version of ethnic identities on the diverse people of Ethiopia.

The T-TPLF achieved control and exploitation of the majority populations by creating a bogus ethnic federalism and dividing them along ethnic, regional, religious lines using the politics of identity, historical grievances, ethnic demonization and ethnic fear and smear.

Until its ouster in 2018, the minority TPLF regime using a shell organization called “Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front” managed to establish total economic and political dominance in Ethiopia.

What is to be done about xenophobia and ethnophobia?

Xenophobic attacks in South Africa have already strained relations between South Africa and countries whose nationals have been subjected to criminal violence.

For instance, fearing reprisals, the South African government closed its Embassy in Nigeria.

Xenophobic attacks will have severe implications for the future of the Africa Continental Free Trade Agreement which aims to “create a single continental market for goods and services as well as a customs union with free movement of capital and business travelers.”

South Africa with its large manufacturing base could benefit significantly from the Agreement, but with a reputation of endemic xenophobia, that benefit could be in grave peril.

When President Ramaphosa signed the Free Trade Agreement he said, “it would create many opportunities and benefits for South Africa and moreover, would grow and diversify the South African economy through the reduction of inequality and unemployment.”

Xenophobia denialism in South African officialdom must be replaced with increased preventive and investigative law enforcement action and prosecution of suspects.

The newly enacted hate crimes and speech law should be vigorously enforced to protect the rights of foreign nationals.

Because foreign nationals have limited access or fear accessing the justice system, there should be official efforts to reach out to victims and communities affected by xenophobic violence and a system of monitoring and anonymous reporting established.

Civil society institutions in South Africa should maintain independent monitoring and reporting mechanisms on incidents of xenophobic violence and should be first responders to assist victims of mob violence.

South African political, religious, cultural and academic leaders must take an uncompromising stand on xenophobia in much the same way as EFF party leader Julius Malema. They must publicly and and without hesitation condemn criminal actions against foreign nationals.

What is to be done about ethnophobia in Ethiopia?

The antidote to the legacy of ethnic apartheid/ethnic federalism in Ethiopia is Medemer philosophy.

Medemer aims to bring syntheses and synergy to Ethiopia’s contrived ethno-tribal politics. It aims to bring into harmony the politics of identity, communalism and sectarianism into syntheses with nation-building, civility, tolerance, love, understanding and forgiveness.

Medemer creates a simple calculus: Without Oromos, there are no Amharas; without Amharas, there are no Tigreans; without Tigreans there are no Somalis; without Somalis, there are no Sidama; without Sidama, there are not Woleyita; without Woleyita, there are no Afari; without Afari, there are no Harari; without Harari, there are no Anuak; without Anuak, there are no Gurage and on and on. Amharas, Oromos, Tigreans…. and the other groups can work cooperatively and even competitively for their collective betterment and prosperity.

Racism, xenophobia and ethnophobia are “sicknesses of the soul”.

Scapegoating the weak, powerless and defenseless “foreign nationals” is a growing trend.

In 1967, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., in a speech said three great challenges faced mankind: “the evils of racism, economic exploitation, and militarism.”

In 2019, mankind, in addition to the evils mentioned by Dr. King, also faces the evils of xenophobia and ethnophobia, especially in Africa.

In my February 2017 commentary entitled, “The Times They Are A-Changin’ in the Land of Immigrants?”, I wrote about the xenophobia, discrimination, prejudice and unfairness towards “undesirable aliens” and vulnerable groups in America.

Recently, the acting director of US Citizenship and Immigration Services, Ken Cuccinelli proposed a re-writing of the words on the Statute of Liberty: “Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free …”

According to Cuccinelli, it should be revised to read, “Give me your tired and your poor who can stand on their own two feet and who will not become a public charge.”

Huddled masses to be replaced by huddled elites of the world!

We but mirror the world. All the tendencies present in the outer world are to be found in the world of our body. If we could change ourselves, the tendencies in the world would also change. As a man changes his own nature, so does the attitude of the world change towards him.

Could Gandhi have inspired the King of Pop to write the lyrics to his song Man in the Mirror?

I’m starting with the man in the mirror (Who?)

I’m asking him to change his ways (Who?)

And no message could have been any clearer

If you wanna make the world a better place

Take a look at yourself and then make that change

Let all Africans start to change their ways with the (wo)man in the mirror.

Let is be the change we want to see.

Let us not forget every time we point a finger at others, three more are pointing at us.

Xeno(Afro)Phobia in South Africa, Ethnophobia in Ethiopia?

Posted in Al Mariam's Commentaries By almariam On September 23, 2019That is understandable because Mandela in his autobiography, “The Long Walk to Freedom” wrote:

Mandela’s passing in December 2013 was a personal loss for me.

In his memory, I wrote a commentary entitled, “Farewell, My African Prince”.

For years, I have written commentaries in remembrance of the Sharpeville Massacre.

Lately, South Africa has become ground zero for xenophobia in Africa. Accusatory fingers are demonizing of South Africans of being virulently xenophobic against African immigrants in their midst.

That is painful for me because during the anti-apartheid struggle Africans throughout the continent gave shelter to exiled South African freedom fighters and African governments provided material and diplomatic support.

H.I.M. Haile Selassie in his 1963 speech said without peace in Southern Africa, there will be no peace in Africa:

As a college student in the mid-1970s, I was a passionate anti-apartheid advocate, joined demonstrations pushing disinvestment in apartheid South Africa and opposed the so-called Sullivan Principles and constructive engagement.

Our mantra I remember to this day: “Hey, ho ho, apartheid has got to go! Brick by brick, wall by wall, apartheid has to fall!”

To see and hear some South Africans today looting and burning while chanting “Hey, ho, ho, African immigrant must go!” breaks my heart.

Since the advent of majority rule in 1994, many Africans who took a long walk to freedom from their countries to escape political persecution or seek economic opportunity have faced violence, intimidation and persecution in South Africa.

When an outbreak of xenophobic violence occurred in South of Africa earlier this month, 12 “foreign nationals” were confirmed dead and 639 suspects were reportedly arrested. Some 1,000 “foreign-owned” businesses were damaged or destroyed.

Violence against foreign-nationals in South Africa has been taking place since 1994.

Incidents of xenophobic violence in South Africa are well-documented.

In 1998, three “foreign nationals” were thrown out of a moving train between Johannesburg and Pretoria because they were accused of “bringing diseases, taking jobs, the same rhetoric we hear today.”

According to a 1998 Human Rights Watch report, “armed gangs of black South Africans attacked foreign nationals from Malawi, Zimbabwe and Mozambique living in the Alexandra township near Johannesburg for several weeks in 1995 in a drive to ‘clean the township of foreigners’”.

In an outbreak of xenophobic violence in 2008, at least 62 people, including South Africans, were killed, thousands were displaced and many businesses and stores owned by “foreign nationals” were looted and destroyed.

In 2015, African immigrants were burned alive in an act of unspeakable xenophobic savagery.

Much of the xenophobic violence is directed at “foreign nationals” operating small shops and stores in the townships or settlements around them.

Most of the violent attacks have been carried out by black South Africans.

Most of the incidents have taken place in areas experiencing high levels of poverty, unemployment and low levels of social, community and public safety services.

Foreign nationals in these areas are particularly disadvantaged because of language problems, ignorance and fear of reporting crimes to police authorities and inability to access the justice system.

The South African government has long denied the existence of xenophobic attacks.

In 2008, former president Thabo Mbeki declared South Africans are not xenophobic but foreign nationals have been victims of “naked criminal activity”. Mbeki claimed, “There isn’t a population of South Africans who attack other Africans simply because of their nationality.”

In 2015, his successor Jacob Zuma repeated the disclaimer stating, “South Africans are not xenophobic. We do not believe that the actions of a few out of more than 50 million citizens justify the label of xenophobia.”

Current president Cyril Ramaphosa has acknowledged the violence is driven by xenophobia and in a statement “condemned violence against foreign nationals in South Africa” and argued “African development depends on the increased movement of people, goods and services between different countries for all of us to benefit.”

Ramaphosa offered “profuse apologies” to Nigeria. “The incident does not represent what we stand for and the South African police leave no stone unturned, that those involved must be brought to book”.

The one South Africa leader who has not minced words about xenophobic violence is the colorful firebrand leader of Economic Freedom Fighters Party, Julius Malema.

In March 2019, Malema offered his explanation for xenophobia in South Africa:

Malema issued a stern warning:

His remedial prescription is simple:

For the most recent xenophobic violence earlier this month, Malema apologized:

Is there rampant xenophobia in South Africa?

Independent surveys on xenophobia in South Africa point to an endemic problem.

The most comprehensive study on xenophobia in South Africa is found in a 2016 doctoral dissertation.

Several opinion surveys over the past two decades have shown South Africans have low levels of tolerance of immigration or immigrants.

“A 1997 survey showed that just six percent of South Africans were tolerant to immigration. In another survey, 75 percent of South Africans held negative perceptions about black African foreigners.”

“A 2004 study by the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation (CSVR) of attitudes among police officers in the Johannesburg area found that 87% of respondents believed most undocumented immigrants in Johannesburg are involved in crime, despite there being no statistical evidence to substantiate the perception.”

“A national survey of the attitudes of the South African population towards foreign nationals in the country by the South African Migration Project in 2006 found xenophobia to be widespread: South Africans do not want it to be easier for foreign nationals to trade informally with South Africa (59 percent opposed), to start small businesses in South Africa (61 percent opposed) or to obtain South African citizenship (68 percent opposed).”

“A 2012 independent survey showed Distrust of foreigners has increased in South Africa in the four years since a wave of xenophobic violence swept the country. Some 67 percent of South Africans say they do not trust foreigners at all, compared to 60 percent in 2008. Nearly a third of the 2,400 respondents would take action to prevent migrants from moving into their neighbourhood and 36 percent would try to stop them from operating businesses. Forty-four percent were opposed to their country providing protection to asylum seekers. 45 percent saying foreigners should not be allowed to live in the country because they take jobs and benefits away from South Africans.”

Holier-than-thou South Africa?

The old saw it true. “Remember, when you point a finger at someone, there are three more fingers pointing at you.”

Since all eyes are on South Africa today, it is appropriate to ask whether xenophobia is a “mental disease” that afflicts only South Africans.

I should like to argue xenophobia and ethnophobia afflict all African countries to varying degrees.

In the not-too-distant past, there have been instances of xenophobic violence and discrimination against “foreign nationals” in Nigeria, Ghana, Cote d’Ivoire, South Sudan, Botswana, Angola and Zambia.

When global oil prices collapsed in 1983, Nigeria ordered the massive expulsion of illegal Ghanaian migrants working in the country. The argument then is not much different than what the South Africans are saying today. Ghanaians were accused of taking jobs from Nigerians and depressing the labor market.

In 2001, Cote d’Ivoire, home to large numbers of West Africans representing more than a quarter of the population, was accused of failing to curb the growth of xenophobia.

In 2006, the Government of Niger “ordered the expulsion of 150,000 Arab refugees from Chad and neighboring countries who have lived in this West African nation for decades.”

In 2010, concerns were expressed about the rise of “extensive” xenophobic attitudes towards Zimbabweans by Botswanans.

In 2013, there were serious concerns of xenophobia in South Sudan, Africa’s newest state.

In 2016, there were xenophobic attacks in Zambia.

In 2017, in an act of reprisal for an alleged murder, Ghanaians attacked and killed 5 Nigerians.

In 2018, Angola denied the occurrence of xenophobic violence against Congolese migrant workers.

In 1998, following the war between Ethiopia and Eritrea, the government of the Tigrean People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) in Ethiopia undertook a mass expulsion of 20 thousand people alleged to be of Eritrean national origin.

TPLF Prime Minister Meles Zenawi at the time justified his arbitrary expulsion claiming “As long as any foreign national, whether Eritrean or Japanese etc . . . lives in Ethiopia [it is] because of the goodwill of the Ethiopian government. If we say ‘Go, because we do not like the colour of your eyes,’ they have to leave.”

There is no better example of xenophobia that deporting a person because of the color of his eyes or national origin.

Xenophobes and criminals?

Xenophobia (Greek xeno “stranger”, phobia “fear”) is not a crime. It is the “irrational, pathological fear or distrust of strangers”. Often, it manifests itself in acts of hostility, violence and discrimination against foreigners.

Are the South Africans who committed the acts of violence against other African “foreign nationals” xenophobes and/or hooligans/criminals?

The survey evidence is clear that xenophobia is a problem in South Africa, but I believe the infinitesimally small number of individuals who commit acts of violence, intimidation and looting are criminals, thugs, gangsters and hooligans.

I cannot believe the mainstream opinion of South Africans supports violent criminal activity against foreigners or others.

But I am not surprised to see anti-immigrant sentiment and violence in a nation where the unemployment rate is nearly 30 percent.

I believe many of the violent acts are committed by poor unemployed youth who have joined either criminal gangs or engage in crimes of opportunity.

Burning immigrants alive, looting and rioting will not create more jobs in South Africa. It will certainly drive away investors and tourists who could be sources of employment.

Foreign nationals are easy victims in South Africa because they have neither a voice nor representation in government and society.

The failure of the South African national government to take effective preventive and prosecutorial action against such criminals is deplorable.

Ethnophobia in Ethiopia

If xenophobia is the “irrational fear or distrust of strangers”, ethnophobia is the irrational fear and hatred of any ethnicity different to one’s own.

In 2018, Ethiopia topped the “global list of highest internal displacement”, according to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Center.

Internal displacement in Ethiopia has been fully documented and has multiple causes. “High levels of vulnerability among rural populations exposed to severe drought and floods, political and resource-based conflict and overstretched government capacity create a high-risk environment in which significant new displacements take place each year.”

However, the principal reason for internal displacement in Ethiopia, in my view, is the structure of internal colonialism created by the TPLF in the ethnic Kilil-istans (similar to South Africa’s Bantustans) which singularly accentuate and exploit ethnic and cultural differences in the country creating conflict and strife.

For instance, the dispute between the Oromia and Somali kilils (regions) resulted in the displacement of hundreds of thousands of people is the outcome of Kililistan politics.

Over 100,000 people fled ethnic violence and became internally displaced persons in Benishangul Gumuz in Western Ethiopia for the same reason.

However, the government of PM Abiy Ahmed effectively implemented an IDP return program in May 2019 “following the announcement of the Federal Government’s Strategic Plan to Address Internal Displacement and a costed Re-covery/Rehabilitation Plan. By the end of May, most IDP sites/camps were dismantled, in East/West Wollega and Gedeo/West Guji zones.”

It is interesting to note that those who howled and growled about internal displacement in Ethiopia suddenly fell silent when the government of PM Abiy Ahmed returned the displaced persons to their places of origin.

For the past 27 years, the regime of the TPLF has exploited and manipulated the political situation in Ethiopia to maintain itself in power.

Using the kilil system, the TPLF has poisoned the interaction between and among ethnic groups, cultures, traditions, religions and sown ethnic and political misunderstanding, mistrust, unrest and conflict.

Today, the legacy of 27 years of ethnophobic propaganda by the TPLF and the fear, suspicion, intolerance, disinformation and false grievances that are perpetuated by empty barrel pseudo-intellectuals and hordes of social media ignoramuses continue to be a source of aggravation and anxiety.

Xenophobia in South Africa and ethnophobia in Ethiopia are products of racial/ethnic apartheid

Apartheid a virulent form and vestige of European colonialism.

In 1948, the minority white National Party (NP) introduced “apartheid” (“apartness”) as an ideology for the separate development of the various racial groups in South Africa.

NP prime minister Hendrik Verwoerd transformed apartheid into a full-fledged de jure separate development system with the passage of the Promotion of Bantu Self Government Act of 1959 creating 10 Bantu black homelands known as Bantustans.

The central aim of this Act was to fragment and separate black South Africans into small groups so that there would be no black majority aspiring or competing for power, and to make it impossible for them to unify under a single national organization. The Act also aimed to psychologically isolate the black majority while simultaneously de-nationalizing them and depriving them of a common identity.

Strictly enforcing the passbook laws, promoting trial consciousness and using a strategy of divide and rule, the minority white apartheid regime for over four decades succeeded in creating a society riven by ethnic, tribal, religious and regional divisions in South Africa.

Following the apartheid South African model, the TPLF regime created 9 kilils (kililistans or ethnic homelands) and two “chartered cities” in Ethiopia to geographically dismember and fragment regions while establishing a hegemonic regime of ethnic supremacy.

Put simply, the TPLF regime copied the racial apartheid system of South Africa to create an ethnic-based system of internal colonialism.

I have discussed the TPLF’s system of internal colonialism in previous commentaries at length.

I have also discussed the Bantustanization (Kililistanization) of Ethiopia in a previous commentary at length.

Suffice it to say that for 27 years, the TPLF’s internal colonialism succeeded through a systematic campaign of de-Ethiopianization similar to the way the colonial masters de-nationalized the people in their African colonies, created artificial ethnic and other boundaries (kilil homelands) and imposed their version of ethnic identities on the diverse people of Ethiopia.

The T-TPLF achieved control and exploitation of the majority populations by creating a bogus ethnic federalism and dividing them along ethnic, regional, religious lines using the politics of identity, historical grievances, ethnic demonization and ethnic fear and smear.

Until its ouster in 2018, the minority TPLF regime using a shell organization called “Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front” managed to establish total economic and political dominance in Ethiopia.

What is to be done about xenophobia and ethnophobia?

Xenophobic attacks in South Africa have already strained relations between South Africa and countries whose nationals have been subjected to criminal violence.

For instance, fearing reprisals, the South African government closed its Embassy in Nigeria.

Xenophobic attacks will have severe implications for the future of the Africa Continental Free Trade Agreement which aims to “create a single continental market for goods and services as well as a customs union with free movement of capital and business travelers.”

South Africa with its large manufacturing base could benefit significantly from the Agreement, but with a reputation of endemic xenophobia, that benefit could be in grave peril.

When President Ramaphosa signed the Free Trade Agreement he said, “it would create many opportunities and benefits for South Africa and moreover, would grow and diversify the South African economy through the reduction of inequality and unemployment.”

Xenophobia denialism in South African officialdom must be replaced with increased preventive and investigative law enforcement action and prosecution of suspects.

The newly enacted hate crimes and speech law should be vigorously enforced to protect the rights of foreign nationals.

Because foreign nationals have limited access or fear accessing the justice system, there should be official efforts to reach out to victims and communities affected by xenophobic violence and a system of monitoring and anonymous reporting established.

Civil society institutions in South Africa should maintain independent monitoring and reporting mechanisms on incidents of xenophobic violence and should be first responders to assist victims of mob violence.

South African political, religious, cultural and academic leaders must take an uncompromising stand on xenophobia in much the same way as EFF party leader Julius Malema. They must publicly and and without hesitation condemn criminal actions against foreign nationals.

What is to be done about ethnophobia in Ethiopia?

The antidote to the legacy of ethnic apartheid/ethnic federalism in Ethiopia is Medemer philosophy.

Medemer aims to bring syntheses and synergy to Ethiopia’s contrived ethno-tribal politics. It aims to bring into harmony the politics of identity, communalism and sectarianism into syntheses with nation-building, civility, tolerance, love, understanding and forgiveness.

Medemer creates a simple calculus: Without Oromos, there are no Amharas; without Amharas, there are no Tigreans; without Tigreans there are no Somalis; without Somalis, there are no Sidama; without Sidama, there are not Woleyita; without Woleyita, there are no Afari; without Afari, there are no Harari; without Harari, there are no Anuak; without Anuak, there are no Gurage and on and on. Amharas, Oromos, Tigreans…. and the other groups can work cooperatively and even competitively for their collective betterment and prosperity.

Xenophobia is a global problem

Racism, xenophobia and ethnophobia are “sicknesses of the soul”.

Scapegoating the weak, powerless and defenseless “foreign nationals” is a growing trend.

In 1967, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., in a speech said three great challenges faced mankind: “the evils of racism, economic exploitation, and militarism.”

In 2019, mankind, in addition to the evils mentioned by Dr. King, also faces the evils of xenophobia and ethnophobia, especially in Africa.

In my February 2017 commentary entitled, “The Times They Are A-Changin’ in the Land of Immigrants?”, I wrote about the xenophobia, discrimination, prejudice and unfairness towards “undesirable aliens” and vulnerable groups in America.

Recently, the acting director of US Citizenship and Immigration Services, Ken Cuccinelli proposed a re-writing of the words on the Statute of Liberty: “Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free …”

According to Cuccinelli, it should be revised to read, “Give me your tired and your poor who can stand on their own two feet and who will not become a public charge.”

Huddled masses to be replaced by huddled elites of the world!

Over a century ago, Gandhi wrote:

Could Gandhi have inspired the King of Pop to write the lyrics to his song Man in the Mirror?

Let all Africans start to change their ways with the (wo)man in the mirror.

Let is be the change we want to see.

Let us not forget every time we point a finger at others, three more are pointing at us.

Share this:

Related Posts