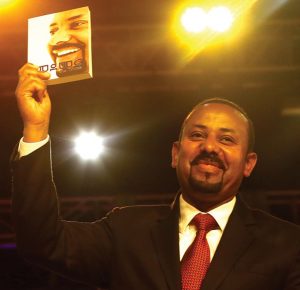

“Medemer” (original in Amharic), Dr. Abiy Ahmed, Prime Minister of Ethiopia and Nobel Peace Laureate 2019, 280 pp. (October 2019)

“Medemer” (original in Amharic), Dr. Abiy Ahmed, Prime Minister of Ethiopia and Nobel Peace Laureate 2019, 280 pp. (October 2019)

Reviewer’s Note:

Part I of my book review on the “philosophy” of Medemer appeared in my October 20, 2019 commentary

My review of “Medemer” is intended for the benefit and convenience of English-speaking audiences who have a sincere desire to understand and rigorously critique “Medemer” philosophy for what it is and is not. I present my personal reflections and perspectives on Medemer philosophy or idea and invite others to review the book and thoughtfully discuss its usefulness and relevance to Ethiopia.

In Part II, I discuss the author’s Medemer praxis in a variety of areas. In a postscript, I shall argue medemer philosophy/praxis is the antidote to political, informational and economic entropy in Ethiopia.

Praxis of Medemer

Medmer is part philosophy/theory and part praxis and as such contains a set of actionable measures and policy prescriptions.

I have previously written on the praxis of Medemer in the context of the distressing, tragic and often aggravating politics of the Horn of Africa and the application of Medemer principles to conflict resolution there.[1] I argued, “What happens in each Horn country affects the others. War in one country threatens the peace in the other. Peace and democracy in one country becomes an example of good governance for others. Regional integration is another phrase for ‘Medemer’.”

Indeed, in a recent speech[2] marking a breakthrough in the Sudan negotiations which resulted in power sharing between the military and civilians, the author explained “the people of Sudan have done well in choosing cooperation over competition which is essential to our collective survival”. He said, the Horn region must “act in synergy” and Medemer becomes a “yarn weaving us together collectively” and help us achieve “collectively what we can only imagine individually”.

In the second part of the book, the author explains the mechanics and application of Medemer to a whole host of issues and problems facing Ethiopia. His analysis begins with a discussion of “two types of oppression”, man-made and other structural. He argues oppression results when governments are unable or unwilling to meet their people’s expectations and demands.

“Man-made oppression” is forged in the minds of people who lack a moral compass and are stone deaf to the voice of their own consciences. They are depravedly indifferent to the suffering of people starving, in poverty or facing abuse and mistreatment. Their sole concern and preoccupation is keeping themselves in power with the barrel of the gun or the power of the almighty birr (dollar). Their guiding philosophy is “might makes right” and “get your money and run.”

“Structural oppression” involves the concerted actions of organized groups within society. The author discusses nine typologies of structural oppression ranging from gender to regime.

The author attributes the persistence of oppression in considerable part to the failure of Ethiopian intellectuals. They generally tend to be narrow-minded, incredibly naïve and misguided because they believe they can implement ideas they have read in books or figments of their imagination. They rarely do strategic planning to implement their ideas into action. They are afflicted by indolence, negligence and indifference. They are impetuous and often prone to emotional reactions casting intellectual rigor to the wind. In sum, Ethiopia sorely lacks grounded and matured intellectuals. The author argues the failure of Ethiopian intellectuals to articulate alternate visions, silence in the face of wrongs, complicity with brutal and corrupt regimes and ineffective leadership styles have contributed to the systemic failure of governance and persistence of oppression.

The author’s answer to dealing with oppression in Ethiopia is establishing genuine multiparty democracy, and he explores various “ways” of doing just that. He argues the essence of democracy is to create a government based on consent and legitimacy. Past experiments trying to establish democracy in Ethiopia based on class struggle, identity politics, the right of secession, etc. have failed. That failure is tied partly to intentional efforts by leaders to prevent the rise of a democratic civic culture and institutions.

The author discusses the principles of direct and representative democracy and their respective (dis)advantages. He explores the distinctions between the trustee (representatives that have sufficient autonomy to deliberate and act in favor of the greater common good and the national interest” and “delegate” models of representation (delegates act only as directed representatives of their constituency with little autonomy”.

The author’s prescription for Ethiopia is a democracy based on “civic nationalism” (reviewer’s translation; an inclusive consensus-based nationalism that thrives on the values of freedom, tolerance, equality, individual rights, etc.) Democracy based on “group rights” is flawed and ineffective. However, the author underscores the singular importance of maintaining diversity in Ethiopian society and respect for cultural, religious and linguistic integrity and protections. Groups should be free to practice their faiths, use their languages in instruction and exercise their cultural practices.

The author discusses the origins and evolution of ethnonationalism and the politics of “nations, nationalities and peoples” in Ethiopia. He argues the politics of ethnic identity, communalism, sectarianism, etc., have led to conflict, strife and war. They have no place in a 21st century Ethiopia.

The author does not see insurmountable problems in reconciling civic nationalism with group rights. Indeed, he believes by creating a consensus/civic-nationalism based democracy it is possible to maximize both individual liberties and group rights to cultural, linguistic and religious autonomy.

Medemer provides the philosophical foundation to build a consensus/civic nationalism-based democracy by creating structures and processes that seek to correct past mistakes, build on existing positive accomplishments and generating innovative new ideas for the future. The author suggests much can be learned from Tunisia’s experience in “civic nationalism”[3] which has contributed significantly to the emergence of a stable multiparty democracy.

The author’s prescription for the practical realization of consensus/civic nationalism-based democracy is pursuit of national reconciliation and development of national understanding on critical issues that are important to the majority of the people in Ethiopia. In the past, national reconciliation has been difficult for various reasons including the shrill exhortations of leaders and activists who seek to maintain the status quo of division and antagonisms for personal political or economic gain.

The author is firmly committed to the pursuit of a process of national reconciliation and goes into the details of how that can be achieved. He also explains how a culture of recrimination has undermined the emergence of such a process. He argues the starting point for a consensus/civic nationalism-based democracy in Ethiopia is the building of a long-term political culture and system based on consent, civic engagement, inclusiveness, accountability, transparency, etc. This requires setting up new, independent and viable civic institutions and practices that promote civility, tolerance, rule of law, accountability, transparency, etc. Existing institutions could also be enhanced and improved.

The current system of nepotism and crony capitalism in Ethiopia must be replaced by institutions that ensure equal opportunity for all. The system and structure of patrimonialism (power flows directly from the leader) and neopatrimonialism (use of state resources in order to secure the loyalty of clients in the general population) must be uprooted and replaced by systems, institutions and processes that are founded on economic and social justice.

The author proposes Ethiopians use their commonly shared values that have been the bedrock of their common heritage to develop consensus. Ethiopians have lived in peace and harmony for much of their history. They have shed their blood together against foreign aggression time and again as one people. They share deeply-rooted faith, cultural and family ties.

However, as a preliminary step to developing national consensus, the politics of stagnation (reviewer’s translation; those resistant to change or do not change with change, “sticks in the mud”) and the defeatist malaise that has pervaded Ethiopian society over the past decades must be transformed by a dynamic medemer politics where all have an equal opportunity to engage and contribute. No man, woman or child will be left behind.

The author argues creating strong institutions to support a democratic structure and process requires significant reforms to existing institutions. The bureaucracy and civil service institutions require major overhaul and professionalization. The bureaucratic culture of malingering, indifference to public concerns and needs, the lack of skills and professional capacity, improper political interference and lack of capacity political interference need to be addressed swiftly.

In Ethiopia’s new consensus/civic nationalism-based democracy, there must be a shift from “ruling” (by force, (neo)patrimonialism) to leadership by consent, legitimacy and moral authority. There are many leadership challenges in Ethiopia. Political leaders in the past have failed to forge common goals to focus the people’s energies and attention. Leaders have lacked a broader vision for the society and instead have tried to promote their own self-interests. They have lacked popular support, good will and legitimacy. They do not have moral/social capital or broad popular acceptance. They tend to respond with emotionalism instead of considered judgment. They have little understanding of the public mood and sentiments. They lack self-control.

To have an effective democratic transition, Ethiopians need to adopt affirmative and positive values such as self-initiative, self-awareness, global thinking, ethical behavior (goodness), pursuit of happiness without infringing on the rights of others, goodwill, security, decency, service volunteerism and so on.

The author argues the command economy of the past has failed and the time is ripe to follow free market principles. The role of government in the economy should be limited to encouraging the expansion of the private sector, attracting and supporting private investment and intervening strategically to strengthen, regulate and create markets. The problem in the past has been excessive state intervention in certain areas and indifference in others. The state should play a decisive role in policy selection, improving the regulatory environment, monetary and fiscal policy.

The author spends a great deal of time discussing Ethiopia’s economic problems and ways of addressing them. He has serious misgivings about the economic legacy of the past quarter century. While Ethiopia has made significant economic gains, the author laments the fact that the price for those gains has been massive debt, runaway government spending, abuse, waste and corruption in the use of public funds. The author recognizes the reality that Ethiopia’s economy is not built on creating opportunities for ordinary people. The massive inequality and maldistribution of wealth inequality, lack of economic justice, rise in the cost of living, etc., in society have roots in an economy based on crony capitalism which only gives lip service to the interests of ordinary people.

The author acknowledges the debt-based economic development has helped a few in particular sectors of the economy. While clients of previous regime have experienced extraordinary improvements in their standard of living, the vast majority of Ethiopians remain in abject poverty. There is massive youth unemployment. Fiscal policy to increase government revenue has not generated sufficient tax revenues. Domestic savings and investments are low and as a result Ethiopia has to depend on foreign sources to cover its balance of payment and foreign exchange deficits. Due to chronic shortages of foreign exchange, Ethiopia is unable to import light industry and mechanize its agricultural sector and basic necessities have to be imported.

The author identifies various reasons for the country’s economic problems. Among these are lack of economic process, a stagnant private sector, lack of coordination between economic actors, lack of markets and good governance, structural obstacles to creating wealth and inability of individuals and groups to effectively participate in the market, lack of knowledge and trust, absence of a level playing field and formal and informal monopoly of markets.

The author perceives a very weak (broken) economic structure in Ethiopia. Though market and governance deficiencies are critical problems, the main economic culprit fingered is deficiency of process/system (sirat) which incorporates key economic actors, lack of knowledge and confidence in the market economy. The market deficiency is manifest in a variety of ways: imbalances in supply and demand, lack of market information, absence of effective regulatory scheme to prevent concentration of economic power in few hands, a very weak private sector and so on.

The author’s prescription to overcome these problems is to enhance and strengthen the private sector by strategic and limited government intervention. Government can play many critical roles in the economy, e.g. building educational and technological infrastructure, expanding logistics, improvements in the bureaucracy, funding research and development, strengthening accountability structures and transparency processes. Government can correct distortions in the economy through regulation, strategic intervention, fiscal and monetary policy. In the past, there has been too much government interference which has stifled private entrepreneurship. There has been lack of constructive engagement of the private sector, government negligence, incompetence and indifference in various aspects of the economy and lack of good monetary and fiscal policy.

The author argues one of the major areas of economic failure has been management of public development projects which have been plagued by corruption, mismanagement, lack of accountability and transparency. Enhancing and strengthening the administrative structure of public projects is vital. Other problems include crony capitalism, fraud, waste and abuse of resources, lack of systems and processes and coordination of economic and political institutions.

The current development model must be changed. Manifestly, that is a change from the so-called “developmental state” model led by the state which has created a massive kleptocracy to a medemer economy where the economic rules of the game are fair, transparent and supportive of private entrepreneurship. Ethiopia can no longer afford to pursue old economic theories in an era of globalization and a world economy that is knowledge- and technologically-based. He emphasizes the role of education in general and gives special attention to higher education to drive Ethiopia’s economy. He perceives the lack of technical and technology-based education as one of the major obstacles to economic success. The economy does not create or support technological innovations and technical education in the country is at the lowest level.

The author argues civil society institutions play critical role in the economy and society. There are over three thousand NGOs in the country that can help balance the government and private sectors. Special attention must be given to the role of youth in the economy in light of the fact that over 70 percent of the population (youth bulge) is under 35 years of age and a much higher percentage live in non-urban areas. He sees a central role for the young small holder farmers. He argues there is much potential economic power in this population. At the core of the economic problems of the country is the inability to provide employment to rural youth who end up migrating to urban areas in search of opportunity.

The author is optimistic Ethiopia can overcome its enormous economic problems if the people practice medemer philosophy and work together in common cause and purpose. Ethiopia has enormous natural resources though they are not developed. Ethiopia has gold, platinum, nickel, copper, gypsum oil and gas which could be responsibly produced. It has substantial livestock population and vast potential for fisheries industry. Ethiopian can become a breadbasket for the rest of Africa given its weather and natural terrain.

Ethiopia has the potential for economic leapfrogging through technology and mechanization. Priority should be given to mechanizing agriculture and improving farming techniques. Industrialization which is now concentrated in the outskirts of urban areas needs to be spread out more evenly.

In the last part of the book, the author addresses medemer principles of foreign policy. He notes the rise of nationalism globally and spread of radical right movements. He discusses the political gains such groups have made in Western countries and the anti-immigrant sentiments feeding the nationalist backlash. He perceives the rise of nationalism as episodic and not as a fundamental shift or political realignment. He believes the world is moving in the direction of medemer and not fragmentation. Globalization and information technology have created a global village. Returning to the old tribal village by retreating to racial, ethnic, identity, ideological and religious is not practical in the 21st century.

In the field of international relations, the author argues Ethiopia should follow a foreign policy based on medemer principles which include competition and cooperation. He believes building relationships based on trust and mutuality of interests is far more effective than zero sum competition. Ethiopia will take the approach of working collectively with neighbors on common issues over which there is consensus and build trust and understanding to work on other issues. Common issues include peace and regional security. He identifies problems of Ethiopian refuges, exiles and migrant workers and the suffering and challenges they face. The government must take measures to ensure they are treated with dignity and justice.

In the last couple of pages of the book, the author speaks passionately about the role of the diaspora in shaping Ethiopia’s destiny and in citizen diplomacy in their host countries. He sees many roles for diaspora Ethiopians in promoting investments and tourism, channeling remittances through established banking services to increase the country’s foreign exchange reserves and in changing the image of Ethiopia.

Medemer offers thought provoking and compelling arguments and analysis to reimagine and even reengineer Ethiopian politics and economics based on synergy, consensus and cooperation. I suspect those who have find themselves trapped in a time warp of socialist, revolutionary democracy and developmental state ideologies are likely to find the ideas in the book maddening. Those who are not willing to take the time and digest the author’s analysis will latch on a word or phrase and spin it to discredit the ideas. Those who read the book with closed minds and visceral opposition to the author’s political leadership will find the book challenging and thought-provoking. Those who read it with an open mind will find much that is inspiring, compelling and intellectually rewarding.

I have found compelling arguments and analysis in “Medemer”. In future commentaries, I hope to explore specific aspects of medemer philosophy and engage those ready, willing, able in discussions and debates.

POSTSCRIPT: Medemer as the antidote to political, informational and economic entropy in Ethiopia

Entropy (“law of disorder”) is a term in physics (thermodynamics) used to describe/measure molecular disorder or randomness of a system. In nature (universe), there is always a “struggle” between order and disorder.

In Ethiopia today, the Lords of Entropy and Agents of Disorder (The LEAD) are working 24/7 to create chaos, discord, anarchy and lawlessness. They jockey with each other to unleash death, destruction, alarm, fear and loathing.

There are the political LEAD

The LEAD who were kicked out on their tails after 27 years of operating a barefaced kleptocracy are licking their wounds to their pride and hanging out in hotels and bars boozed, buzzed and defanged. They spend their stolen billions paying off unemployed youths to engage in ethnic violence and destabilizing criminal activity.

There are the LEAD who are activists-cum-terrorists instigating violence and lawlessness. They use social media to recruit virtual suicide bombers and the conventional media to organize a ragtag thug army.

There are the faceless and nameless invisible LEAD who hide in the bureaucracy and government offices resisting any and all reforms and punishing the public by unleashing hardship and inconvenience.

There are the Chicken Little LEAD who spread rumor and gossip because they believe the sky is falling down their heads.

There are the digital/information LEAD.

These are the social media nitwits and ignoramus LEAD who live in Fakebook, NiTwitterdom and propagate numbing videos of lies, disinformation and hate.

There are social media thug LEAD who call themselves “digital this or that” and coordinate campaigns of lies and disinformation to cause conflict and strife so that their bosses could return to power. (That will happen when hell freezes over and the Prince of Darkness and his lackey demons go ice skating.)

There are the YouTube click bait LEAD who traffic in bad and fake news to score a few pennies from Google. They sensationalize and exaggerate news to terrorize, spread panic, alarm, anxiety, and fears among those who are not internet savvy.

There are the empty barrel, clueless pseudo-intellectual LEAD with the brain power of jellyfish that appear as talking heads on YouTube and such and barf words of hate and division.

The digital LEAD think political power grows out the web pages of Facebook, Twitter and YouTube.

They have neither the capacity nor will to engage in organized political competition or battle of ideas. They hope to exploit the ignorance of the masses with belligerent megalomaniacal words of hate, war and rumors of war.

The unvarnished truth is that the LEAD are a cancer on the Ethiopian body politic. They are losers in their personal, professional, political and social lives. Having thoroughly messed up their lives, now they want to mess up everybody else’s. They want to drag down everyone into their miserable world of endless gloom and doom. Losers always lose and the LEAD will lose everything.

But there is no need to fear the LEAD. They are all paper tigers, daylight hyenas, barking dogs and crybabies.

They become empowered when we give them attention and show fear.

The LEAD will lead Ethiopia down a path of division and destruction.

But we must always be mindful of this fact: The disorder created by few should be a good reminder to the many what the alternatives are.

In the absence of medemer, the inmates will take over the mental asylum.

Let there be no doubt: Medemer forces will create order regardless of how much the Forces of LEAD try to create disorder.

Medemer is a philosophy for winners.

Medemer is a labor of love. It creates order out of disorder. It brings unity out of division. It is a healing balm on the festering wounds of hate, division and distrust.

Medemer is about hope and confidence in a better future, a brave new Ethiopia.

Medemer is about peace. By practicing medemer philosophy, Abiy Ahmed has won the Nobel Prize for Peace in 2019.

Medemer is about love, forgiveness and reconciliation.

Medemer is about creating a new national political architecture founded on consensus based civic nationalism and multiparty democracy.

Medemer is in Ethiopia to stay because the alternative is to be enslaved by the LEAD.

I have made many prophesies over the years that have come to pass.

Here is my prophesy for all LEAD in and out of Ethiopia: “Their sword shall enter into their own hearts, and their bows shall be broken.”

The Lords of Entropy and Agents of Disorder in Ethiopia will be defeated with Medemer philosophy in the final battle of ideas, in the final battle for the hearts and minds of the Ethiopian people!

MEDEMER MESSAGE TO LEAD:

GIVE IT UP.

RESISTANCE TO MEDEMER IS FUTILE!

=====================

[1] http://almariam.com/2019/03/07/the-praxis-of-medemer-in-the-horn-of-africa/

[2] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i_ZZRjGlRyQ&feature=youtu.be

[3] See, e.g. Veronica Baker, “For a state to maintain its democratic status and protect against despotism requires citizens to embrace civic values (the elements of civic culture that train citizens in activism, reason, and engagement) that help them shape their own political lives. The resultant civil society is a natural extension of these individual-held values, expressed collectively to achieve community goals.” https://scholar.colorado.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2212&context=honr_theses

“Medemer” by Abiy Ahmed, Ph.D., An Interpretive Book Review, (Part II)- Working Through Political Entropy in Ethiopia With Medemer

Posted in Al Mariam's Commentaries By almariam On October 28, 2019Reviewer’s Note:

Part I of my book review on the “philosophy” of Medemer appeared in my October 20, 2019 commentary

My review of “Medemer” is intended for the benefit and convenience of English-speaking audiences who have a sincere desire to understand and rigorously critique “Medemer” philosophy for what it is and is not. I present my personal reflections and perspectives on Medemer philosophy or idea and invite others to review the book and thoughtfully discuss its usefulness and relevance to Ethiopia.

In Part II, I discuss the author’s Medemer praxis in a variety of areas. In a postscript, I shall argue medemer philosophy/praxis is the antidote to political, informational and economic entropy in Ethiopia.

Praxis of Medemer

Medmer is part philosophy/theory and part praxis and as such contains a set of actionable measures and policy prescriptions.

I have previously written on the praxis of Medemer in the context of the distressing, tragic and often aggravating politics of the Horn of Africa and the application of Medemer principles to conflict resolution there.[1] I argued, “What happens in each Horn country affects the others. War in one country threatens the peace in the other. Peace and democracy in one country becomes an example of good governance for others. Regional integration is another phrase for ‘Medemer’.”

Indeed, in a recent speech[2] marking a breakthrough in the Sudan negotiations which resulted in power sharing between the military and civilians, the author explained “the people of Sudan have done well in choosing cooperation over competition which is essential to our collective survival”. He said, the Horn region must “act in synergy” and Medemer becomes a “yarn weaving us together collectively” and help us achieve “collectively what we can only imagine individually”.

In the second part of the book, the author explains the mechanics and application of Medemer to a whole host of issues and problems facing Ethiopia. His analysis begins with a discussion of “two types of oppression”, man-made and other structural. He argues oppression results when governments are unable or unwilling to meet their people’s expectations and demands.

“Man-made oppression” is forged in the minds of people who lack a moral compass and are stone deaf to the voice of their own consciences. They are depravedly indifferent to the suffering of people starving, in poverty or facing abuse and mistreatment. Their sole concern and preoccupation is keeping themselves in power with the barrel of the gun or the power of the almighty birr (dollar). Their guiding philosophy is “might makes right” and “get your money and run.”

“Structural oppression” involves the concerted actions of organized groups within society. The author discusses nine typologies of structural oppression ranging from gender to regime.

The author attributes the persistence of oppression in considerable part to the failure of Ethiopian intellectuals. They generally tend to be narrow-minded, incredibly naïve and misguided because they believe they can implement ideas they have read in books or figments of their imagination. They rarely do strategic planning to implement their ideas into action. They are afflicted by indolence, negligence and indifference. They are impetuous and often prone to emotional reactions casting intellectual rigor to the wind. In sum, Ethiopia sorely lacks grounded and matured intellectuals. The author argues the failure of Ethiopian intellectuals to articulate alternate visions, silence in the face of wrongs, complicity with brutal and corrupt regimes and ineffective leadership styles have contributed to the systemic failure of governance and persistence of oppression.

The author’s answer to dealing with oppression in Ethiopia is establishing genuine multiparty democracy, and he explores various “ways” of doing just that. He argues the essence of democracy is to create a government based on consent and legitimacy. Past experiments trying to establish democracy in Ethiopia based on class struggle, identity politics, the right of secession, etc. have failed. That failure is tied partly to intentional efforts by leaders to prevent the rise of a democratic civic culture and institutions.

The author discusses the principles of direct and representative democracy and their respective (dis)advantages. He explores the distinctions between the trustee (representatives that have sufficient autonomy to deliberate and act in favor of the greater common good and the national interest” and “delegate” models of representation (delegates act only as directed representatives of their constituency with little autonomy”.

The author’s prescription for Ethiopia is a democracy based on “civic nationalism” (reviewer’s translation; an inclusive consensus-based nationalism that thrives on the values of freedom, tolerance, equality, individual rights, etc.) Democracy based on “group rights” is flawed and ineffective. However, the author underscores the singular importance of maintaining diversity in Ethiopian society and respect for cultural, religious and linguistic integrity and protections. Groups should be free to practice their faiths, use their languages in instruction and exercise their cultural practices.

The author discusses the origins and evolution of ethnonationalism and the politics of “nations, nationalities and peoples” in Ethiopia. He argues the politics of ethnic identity, communalism, sectarianism, etc., have led to conflict, strife and war. They have no place in a 21st century Ethiopia.

The author does not see insurmountable problems in reconciling civic nationalism with group rights. Indeed, he believes by creating a consensus/civic-nationalism based democracy it is possible to maximize both individual liberties and group rights to cultural, linguistic and religious autonomy.

Medemer provides the philosophical foundation to build a consensus/civic nationalism-based democracy by creating structures and processes that seek to correct past mistakes, build on existing positive accomplishments and generating innovative new ideas for the future. The author suggests much can be learned from Tunisia’s experience in “civic nationalism”[3] which has contributed significantly to the emergence of a stable multiparty democracy.

The author’s prescription for the practical realization of consensus/civic nationalism-based democracy is pursuit of national reconciliation and development of national understanding on critical issues that are important to the majority of the people in Ethiopia. In the past, national reconciliation has been difficult for various reasons including the shrill exhortations of leaders and activists who seek to maintain the status quo of division and antagonisms for personal political or economic gain.

The author is firmly committed to the pursuit of a process of national reconciliation and goes into the details of how that can be achieved. He also explains how a culture of recrimination has undermined the emergence of such a process. He argues the starting point for a consensus/civic nationalism-based democracy in Ethiopia is the building of a long-term political culture and system based on consent, civic engagement, inclusiveness, accountability, transparency, etc. This requires setting up new, independent and viable civic institutions and practices that promote civility, tolerance, rule of law, accountability, transparency, etc. Existing institutions could also be enhanced and improved.

The current system of nepotism and crony capitalism in Ethiopia must be replaced by institutions that ensure equal opportunity for all. The system and structure of patrimonialism (power flows directly from the leader) and neopatrimonialism (use of state resources in order to secure the loyalty of clients in the general population) must be uprooted and replaced by systems, institutions and processes that are founded on economic and social justice.

The author proposes Ethiopians use their commonly shared values that have been the bedrock of their common heritage to develop consensus. Ethiopians have lived in peace and harmony for much of their history. They have shed their blood together against foreign aggression time and again as one people. They share deeply-rooted faith, cultural and family ties.

However, as a preliminary step to developing national consensus, the politics of stagnation (reviewer’s translation; those resistant to change or do not change with change, “sticks in the mud”) and the defeatist malaise that has pervaded Ethiopian society over the past decades must be transformed by a dynamic medemer politics where all have an equal opportunity to engage and contribute. No man, woman or child will be left behind.

The author argues creating strong institutions to support a democratic structure and process requires significant reforms to existing institutions. The bureaucracy and civil service institutions require major overhaul and professionalization. The bureaucratic culture of malingering, indifference to public concerns and needs, the lack of skills and professional capacity, improper political interference and lack of capacity political interference need to be addressed swiftly.

In Ethiopia’s new consensus/civic nationalism-based democracy, there must be a shift from “ruling” (by force, (neo)patrimonialism) to leadership by consent, legitimacy and moral authority. There are many leadership challenges in Ethiopia. Political leaders in the past have failed to forge common goals to focus the people’s energies and attention. Leaders have lacked a broader vision for the society and instead have tried to promote their own self-interests. They have lacked popular support, good will and legitimacy. They do not have moral/social capital or broad popular acceptance. They tend to respond with emotionalism instead of considered judgment. They have little understanding of the public mood and sentiments. They lack self-control.

To have an effective democratic transition, Ethiopians need to adopt affirmative and positive values such as self-initiative, self-awareness, global thinking, ethical behavior (goodness), pursuit of happiness without infringing on the rights of others, goodwill, security, decency, service volunteerism and so on.

The author argues the command economy of the past has failed and the time is ripe to follow free market principles. The role of government in the economy should be limited to encouraging the expansion of the private sector, attracting and supporting private investment and intervening strategically to strengthen, regulate and create markets. The problem in the past has been excessive state intervention in certain areas and indifference in others. The state should play a decisive role in policy selection, improving the regulatory environment, monetary and fiscal policy.

The author spends a great deal of time discussing Ethiopia’s economic problems and ways of addressing them. He has serious misgivings about the economic legacy of the past quarter century. While Ethiopia has made significant economic gains, the author laments the fact that the price for those gains has been massive debt, runaway government spending, abuse, waste and corruption in the use of public funds. The author recognizes the reality that Ethiopia’s economy is not built on creating opportunities for ordinary people. The massive inequality and maldistribution of wealth inequality, lack of economic justice, rise in the cost of living, etc., in society have roots in an economy based on crony capitalism which only gives lip service to the interests of ordinary people.

The author acknowledges the debt-based economic development has helped a few in particular sectors of the economy. While clients of previous regime have experienced extraordinary improvements in their standard of living, the vast majority of Ethiopians remain in abject poverty. There is massive youth unemployment. Fiscal policy to increase government revenue has not generated sufficient tax revenues. Domestic savings and investments are low and as a result Ethiopia has to depend on foreign sources to cover its balance of payment and foreign exchange deficits. Due to chronic shortages of foreign exchange, Ethiopia is unable to import light industry and mechanize its agricultural sector and basic necessities have to be imported.

The author identifies various reasons for the country’s economic problems. Among these are lack of economic process, a stagnant private sector, lack of coordination between economic actors, lack of markets and good governance, structural obstacles to creating wealth and inability of individuals and groups to effectively participate in the market, lack of knowledge and trust, absence of a level playing field and formal and informal monopoly of markets.

The author perceives a very weak (broken) economic structure in Ethiopia. Though market and governance deficiencies are critical problems, the main economic culprit fingered is deficiency of process/system (sirat) which incorporates key economic actors, lack of knowledge and confidence in the market economy. The market deficiency is manifest in a variety of ways: imbalances in supply and demand, lack of market information, absence of effective regulatory scheme to prevent concentration of economic power in few hands, a very weak private sector and so on.

The author’s prescription to overcome these problems is to enhance and strengthen the private sector by strategic and limited government intervention. Government can play many critical roles in the economy, e.g. building educational and technological infrastructure, expanding logistics, improvements in the bureaucracy, funding research and development, strengthening accountability structures and transparency processes. Government can correct distortions in the economy through regulation, strategic intervention, fiscal and monetary policy. In the past, there has been too much government interference which has stifled private entrepreneurship. There has been lack of constructive engagement of the private sector, government negligence, incompetence and indifference in various aspects of the economy and lack of good monetary and fiscal policy.

The author argues one of the major areas of economic failure has been management of public development projects which have been plagued by corruption, mismanagement, lack of accountability and transparency. Enhancing and strengthening the administrative structure of public projects is vital. Other problems include crony capitalism, fraud, waste and abuse of resources, lack of systems and processes and coordination of economic and political institutions.

The current development model must be changed. Manifestly, that is a change from the so-called “developmental state” model led by the state which has created a massive kleptocracy to a medemer economy where the economic rules of the game are fair, transparent and supportive of private entrepreneurship. Ethiopia can no longer afford to pursue old economic theories in an era of globalization and a world economy that is knowledge- and technologically-based. He emphasizes the role of education in general and gives special attention to higher education to drive Ethiopia’s economy. He perceives the lack of technical and technology-based education as one of the major obstacles to economic success. The economy does not create or support technological innovations and technical education in the country is at the lowest level.

The author argues civil society institutions play critical role in the economy and society. There are over three thousand NGOs in the country that can help balance the government and private sectors. Special attention must be given to the role of youth in the economy in light of the fact that over 70 percent of the population (youth bulge) is under 35 years of age and a much higher percentage live in non-urban areas. He sees a central role for the young small holder farmers. He argues there is much potential economic power in this population. At the core of the economic problems of the country is the inability to provide employment to rural youth who end up migrating to urban areas in search of opportunity.

The author is optimistic Ethiopia can overcome its enormous economic problems if the people practice medemer philosophy and work together in common cause and purpose. Ethiopia has enormous natural resources though they are not developed. Ethiopia has gold, platinum, nickel, copper, gypsum oil and gas which could be responsibly produced. It has substantial livestock population and vast potential for fisheries industry. Ethiopian can become a breadbasket for the rest of Africa given its weather and natural terrain.

Ethiopia has the potential for economic leapfrogging through technology and mechanization. Priority should be given to mechanizing agriculture and improving farming techniques. Industrialization which is now concentrated in the outskirts of urban areas needs to be spread out more evenly.

In the last part of the book, the author addresses medemer principles of foreign policy. He notes the rise of nationalism globally and spread of radical right movements. He discusses the political gains such groups have made in Western countries and the anti-immigrant sentiments feeding the nationalist backlash. He perceives the rise of nationalism as episodic and not as a fundamental shift or political realignment. He believes the world is moving in the direction of medemer and not fragmentation. Globalization and information technology have created a global village. Returning to the old tribal village by retreating to racial, ethnic, identity, ideological and religious is not practical in the 21st century.

In the field of international relations, the author argues Ethiopia should follow a foreign policy based on medemer principles which include competition and cooperation. He believes building relationships based on trust and mutuality of interests is far more effective than zero sum competition. Ethiopia will take the approach of working collectively with neighbors on common issues over which there is consensus and build trust and understanding to work on other issues. Common issues include peace and regional security. He identifies problems of Ethiopian refuges, exiles and migrant workers and the suffering and challenges they face. The government must take measures to ensure they are treated with dignity and justice.

In the last couple of pages of the book, the author speaks passionately about the role of the diaspora in shaping Ethiopia’s destiny and in citizen diplomacy in their host countries. He sees many roles for diaspora Ethiopians in promoting investments and tourism, channeling remittances through established banking services to increase the country’s foreign exchange reserves and in changing the image of Ethiopia.

Medemer offers thought provoking and compelling arguments and analysis to reimagine and even reengineer Ethiopian politics and economics based on synergy, consensus and cooperation. I suspect those who have find themselves trapped in a time warp of socialist, revolutionary democracy and developmental state ideologies are likely to find the ideas in the book maddening. Those who are not willing to take the time and digest the author’s analysis will latch on a word or phrase and spin it to discredit the ideas. Those who read the book with closed minds and visceral opposition to the author’s political leadership will find the book challenging and thought-provoking. Those who read it with an open mind will find much that is inspiring, compelling and intellectually rewarding.

I have found compelling arguments and analysis in “Medemer”. In future commentaries, I hope to explore specific aspects of medemer philosophy and engage those ready, willing, able in discussions and debates.

POSTSCRIPT: Medemer as the antidote to political, informational and economic entropy in Ethiopia

Entropy (“law of disorder”) is a term in physics (thermodynamics) used to describe/measure molecular disorder or randomness of a system. In nature (universe), there is always a “struggle” between order and disorder.

In Ethiopia today, the Lords of Entropy and Agents of Disorder (The LEAD) are working 24/7 to create chaos, discord, anarchy and lawlessness. They jockey with each other to unleash death, destruction, alarm, fear and loathing.

There are the political LEAD

The LEAD who were kicked out on their tails after 27 years of operating a barefaced kleptocracy are licking their wounds to their pride and hanging out in hotels and bars boozed, buzzed and defanged. They spend their stolen billions paying off unemployed youths to engage in ethnic violence and destabilizing criminal activity.

There are the LEAD who are activists-cum-terrorists instigating violence and lawlessness. They use social media to recruit virtual suicide bombers and the conventional media to organize a ragtag thug army.

There are the faceless and nameless invisible LEAD who hide in the bureaucracy and government offices resisting any and all reforms and punishing the public by unleashing hardship and inconvenience.

There are the Chicken Little LEAD who spread rumor and gossip because they believe the sky is falling down their heads.

There are the digital/information LEAD.

These are the social media nitwits and ignoramus LEAD who live in Fakebook, NiTwitterdom and propagate numbing videos of lies, disinformation and hate.

There are social media thug LEAD who call themselves “digital this or that” and coordinate campaigns of lies and disinformation to cause conflict and strife so that their bosses could return to power. (That will happen when hell freezes over and the Prince of Darkness and his lackey demons go ice skating.)

There are the YouTube click bait LEAD who traffic in bad and fake news to score a few pennies from Google. They sensationalize and exaggerate news to terrorize, spread panic, alarm, anxiety, and fears among those who are not internet savvy.

There are the empty barrel, clueless pseudo-intellectual LEAD with the brain power of jellyfish that appear as talking heads on YouTube and such and barf words of hate and division.

The digital LEAD think political power grows out the web pages of Facebook, Twitter and YouTube.

They have neither the capacity nor will to engage in organized political competition or battle of ideas. They hope to exploit the ignorance of the masses with belligerent megalomaniacal words of hate, war and rumors of war.

The unvarnished truth is that the LEAD are a cancer on the Ethiopian body politic. They are losers in their personal, professional, political and social lives. Having thoroughly messed up their lives, now they want to mess up everybody else’s. They want to drag down everyone into their miserable world of endless gloom and doom. Losers always lose and the LEAD will lose everything.

But there is no need to fear the LEAD. They are all paper tigers, daylight hyenas, barking dogs and crybabies.

They become empowered when we give them attention and show fear.

The LEAD will lead Ethiopia down a path of division and destruction.

But we must always be mindful of this fact: The disorder created by few should be a good reminder to the many what the alternatives are.

In the absence of medemer, the inmates will take over the mental asylum.

Let there be no doubt: Medemer forces will create order regardless of how much the Forces of LEAD try to create disorder.

Medemer is a philosophy for winners.

Medemer is a labor of love. It creates order out of disorder. It brings unity out of division. It is a healing balm on the festering wounds of hate, division and distrust.

Medemer is about hope and confidence in a better future, a brave new Ethiopia.

Medemer is about peace. By practicing medemer philosophy, Abiy Ahmed has won the Nobel Prize for Peace in 2019.

Medemer is about love, forgiveness and reconciliation.

Medemer is about creating a new national political architecture founded on consensus based civic nationalism and multiparty democracy.

Medemer is in Ethiopia to stay because the alternative is to be enslaved by the LEAD.

I have made many prophesies over the years that have come to pass.

Here is my prophesy for all LEAD in and out of Ethiopia: “Their sword shall enter into their own hearts, and their bows shall be broken.”

The Lords of Entropy and Agents of Disorder in Ethiopia will be defeated with Medemer philosophy in the final battle of ideas, in the final battle for the hearts and minds of the Ethiopian people!

MEDEMER MESSAGE TO LEAD:

GIVE IT UP.

RESISTANCE TO MEDEMER IS FUTILE!

=====================

[1] http://almariam.com/2019/03/07/the-praxis-of-medemer-in-the-horn-of-africa/

[2] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i_ZZRjGlRyQ&feature=youtu.be

[3] See, e.g. Veronica Baker, “For a state to maintain its democratic status and protect against despotism requires citizens to embrace civic values (the elements of civic culture that train citizens in activism, reason, and engagement) that help them shape their own political lives. The resultant civil society is a natural extension of these individual-held values, expressed collectively to achieve community goals.” https://scholar.colorado.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2212&context=honr_theses

Share this:

Related Posts