Indexing Ethiopia

Author’s Note: Last week, Vision of Humanity issued its 2017 Global Peace Index (GPI). Its report on Ethiopia is certainly the most distressing though unequivocal, straightforward and clear-cut. The state of peace worsened in Ethiopia more than any other country in sub-Saharan Africa, and arguably the rest of the world.

Author’s Note: Last week, Vision of Humanity issued its 2017 Global Peace Index (GPI). Its report on Ethiopia is certainly the most distressing though unequivocal, straightforward and clear-cut. The state of peace worsened in Ethiopia more than any other country in sub-Saharan Africa, and arguably the rest of the world.

For someone who is completing his second decade of unrelenting and unwavering struggle for human rights and peaceful change in Ethiopia, the GPI report is heartbreaking and mournful.

Reading between the lines is my profession. When I read the words “the state of peace has worsened in Ethiopia more than any other country”, I know what exactly what that means. I know what the opposite of the absence of civil peace is. When the state of civil peace in Ethiopia is in such dire and grave peril, the unthinkable becomes more real by the day.

I want to think only about civil peace in Ethiopia. Nothing else. I dream of peace and brotherhood and sisterhood among the diverse people of Ethiopia. Peace with equality and justice for all. Peace and understanding without force. Peace offerings among all people of Ethiopia. Peaceful resistance.

I dream of a peaceful Ethiopia where everyone greets each other with “Salam” and “Shalom. I believe all humanity “must turn from evil and do good [and] seek peace and pursue it”, for the “Blessed are the peacemakers.”

I don’t like George Orwell’s 1984 declaration, “War is peace.”

I much prefer Jimi Hendrix’s formulation from the days of my youth, “When the power of love overcomes the love of power, the world will know peace.”

I believe when the power of love overcomes the love of power, Ethiopia will know peace.

In this commentary, I review the latest findings of the various indices on Ethiopia. Peace is a many-splendoured thing.

What do the “Indices” have to say about Ethiopia?

Is there hope for peaceful change in Ethiopia?

Global Peace Index 2017

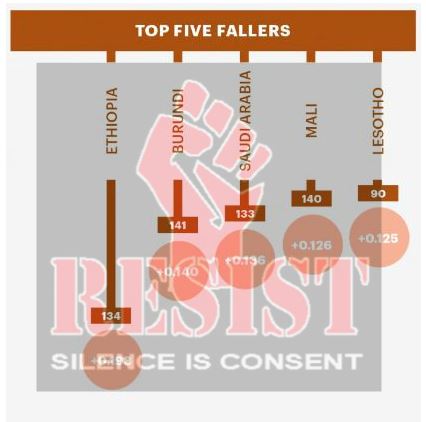

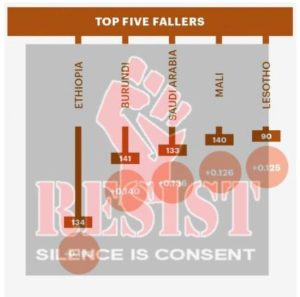

Last week, Vision of Humanity issued its 2017 Global Peace Index (GPI). Ethiopia was #1 on the list of “Top Five Fallers”, followed by Burundi, Saudi Arabia, Mali and Lesotho.

GPI provides “a comprehensive analysis of the state of peace in the world”.

GPI reports the “world slightly improved in peace last year” but the “score for sub-Saharan Africa was influenced by deteriorations in various countries—notably Ethiopia, which worsened more than any other country, reflecting a state of emergency imposed in October 2016 following violent demonstrations.” (Emphasis added.)

Simply stated, the state of peace is in its most precarious and risky state in Ethiopia.

I have been warning for some time that the black apartheid system set up by the Thugtatorship of the Tigrean People’s Party (T-TPLF) has set Ethiopia on a trajectory to civil war. (That is the 600-pound gorilla in the room few dare to talk about openly.) That is why the GPI report is so worrisome and painful to me. It gnaws at my own deep concerns and anxieties about the current state of peace in Ethiopia.

In my December 2016 commentary, I bluntly asked, “Is Ethiopia going in the direction of a civil war?”

In my April 9 commentary, I warned that unlike the masters of apartheid in South Africa who made peace in the nick of time, time to make peace in Ethiopia is running out fast for the T-TPLF.

In my commentary in The Hill last month, I urged passage of the pending human rights bill in the U.S. Congress because “Ethiopia is at a tipping point” now. It is clear what the tipping point is. It is that point of no return.

Failed (Fragile) States Index 2017

Ethiopia is ranked 15th failed state out of 178 on the Failed States Index (FSI) and is rated as “High Alert”. It is #1 on the list of “Most Worsened Country in 2017” in terms of “susceptibility to instability” and “fractionalization and group grievance”.

The FSI is “an assessment of 178 countries based on twelve social, economic, and political indicators that quantify pressures experienced by countries, and thus their susceptibility to instability.”

The FSI devotes a full chapter focusing on Ethiopia (at p. 13) and concludes, “Ethiopia’s overall Fragile States Index (FSI) score has been incrementally worsening over the past decade, moving from 95.3 in 2007, to a score of 101.1 in this year’s 2017 index, with Ethiopia — along with Mexico — being the most worsened country over the past year.”

The FSI points out that, “Tigray elites are perceived to still hold significant political power within the essentially one -party state. Military leadership has also been dominated by Tigrayans, which makes perceptions of Tigray influence within the state apparatus all the more unpalatable to populations that feel increasingly excluded.”

Corruption Perception Index 2016 and Global Financial Integrity

Ethiopia is ranked 108 out of 176 countries on the Corruption Perception Index (CPI).

The CPI ranks countries “by their perceived levels of corruption, as determined by expert assessments and opinion surveys.” The CPI generally defines corruption as “the misuse of public power for private benefit.”

According to CPI, Ethiopia “is among the top ten African countries by cumulative illicit financial flows related to trade mispricing. This amount may be much higher if funds from corruption and other criminal activities are considered.”

According to Global Financial Integrity (GFI) “illicit financial flows out of Ethiopia nearly doubled to US$3.26 Billion in 2009 over the previous year, with corruption, kickbacks and bribery accounting for the vast majority of that increase.” GFI reported, “Ethiopia lost US$11.7 billion to illicit financial outflows between 2000 and 2009.”

U.N. Human Development Index 2017

Ethiopia ranks 174 out of 188 countries on the U.N. Human Development Index (HDI).

The adult literacy rate in Ethiopia is 49.1 percent. Government expenditure on education (as % of GDP) is 4.5. Expected years of schooling (years) is 8.4. The population with at least some secondary education (% aged 25 and older) is 15.8. The pupil-teacher ratio, primary school (number of pupils per teacher) is 64. The primary school dropout rate (% of primary school cohort) is a mind-boggling 63.4.

The HDI is a “measure of average achievement in key dimensions of human development: a long and healthy life, being knowledgeable and have a decent standard of living.”

Economist Democracy Index 2017

The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index (DI) scores 167 countries on a scale of 0 to 10 based on 60 indicators. The indicators are grouped into five different categories measuring pluralism, civil liberties, and political culture.

Ethiopia scores 3.73 on the D.I. and is classified as “authoritarian”.

According to DI, the authoritarian “nations are often absolute dictatorships” with “some conventional institutions of democracy”. Ethiopia scores at the bottom because “infringements and abuses of civil liberties are commonplace, elections- if they take place- are not fair and free, the media is often state-owned or controlled by groups associated with the ruling regime, the judiciary is not independent, and there is omnipresent censorship and suppression of governmental criticism.”

The T-TPLF is an absolute dictatorship which clings to power by an emergency decree.

Economic Freedom of the World Index (EFI) 2016

Ethiopia is classified as “Least Free” on the EFI with a score of 5.60 out of 10. Ethiopia ranked 145 out of 159 countries.

Economic freedom is defined as “(1) personal choice, (2) voluntary exchange coordinated by markets, (3) freedom to enter and compete in markets, and (4) protection of persons and their property from aggression by others.”

To earn high ratings on the EFI, among other things, “a country must provide secure protection of privately owned property, a legal system that treats all equally, even-handed enforcement of contracts, and a stable monetary environment.”

Ethiopia was classified as Least Free on the DI because Ethiopians have little economic freedom when they acquire property. They are often subjected to the use of force, fraud, or theft in property acquisitions and there is little protection from physical invasions by others.

Countries that enjoy high levels of economic freedom manifest “higher average income per person, higher income of the poorest 10%, higher life expectancy, higher literacy, lower infant mortality, higher access to water sources and less corruption.” Because Ethiopia has low levels of economic freedom, it scores very low on measures of literacy, life expectancy and infant mortality.

Bertelsmann Stiftung Transformation Index 2016 (BSI)

Ethiopia is in the rump of the Bertelsmann Stiftung Transformation Index (BTI).

On “Political Transformation”, Ethiopia scored 3.23 (113 out of 129 countries). On “Economic Transformation” Ethiopia scored 3.86 (109 out of 129 countries) followed by 3.48 on the “management index” (108 out of 129).

The BTI analyzes and evaluates the quality of democracy, viability of market economy and political management in 129 developing and transition countries. It “measures successes and setbacks on the path toward a democracy based on the rule of law and a socially responsible market economy.”

The BTI’s detailed and extraordinarily revealing report calls Ethiopia a “façade democracy” and makes certain keen observations:

Ethiopia ‘remains one of Africa’s poorest countries, with a third of the population still living below the poverty line, and its regime is one of the continent’s most authoritarian in character. Between five and seven million people require emergency (donor) food aid throughout the year.’

Ethiopia ‘continues to be categorized as an authoritarian state, a category it shares with neighboring states including Eritrea and Sudan.’

Official results show that the governing-party coalition under the leadership of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) secured a 99% majority in the 2010 polls.

The increased incidence of government land-grabbing activities – the lease of land previously used by smallholders and pastoralists to foreign investment and agrobusiness companies – has prompted heavy unrest in Gambela, in Oromo and other regions. In the western Gambela region, as many as 70,000 people have been forced to move as a result. Women’s rights are protected by legislation, but are routinely violated in practice.

The national parliament (in which the opposition parties held just a single seat during the period under review) is regarded as a rubber-stamp institution, without any influence on decision-making processes within the EPRDF, the sole ruling party for 24 years.

The government maintains a network of paid informants, and opposition politicians have accused the government of tapping their telephones. It is therefore unrealistic to expect that elected parliamentarians can freely and fairly participate in law-making.

Ethiopia does not have an independent judiciary with the ability and autonomy to interpret, monitor and review existing laws, legislation and policies. Access to fair and timely justice for citizens, at least as conventionally defined by legal experts, cannot be said to exist. In general, there are no judges able to render decisions free from the influence of the main political-party leaders, despite these jurists’ professionalism and sincerity. The independence of the judiciary, formally guaranteed by the constitution, is significantly impaired by political authorities and the high levels of corruption. High-level judges are usually appointed or approved by the government. The judiciary functions in ways that usually support the political stances and policies of the government. Pro-government bias is evident in political and media-freedom cases, as well as in business disputes.

Officeholders who break the law and engage in corruption are generally not adequately prosecuted, especially when they belong to the ruling party (EPRDF). In some cases, “disloyal” civil servants are subject to legal action. Corruption remains a significant problem in Ethiopia due to the lack of checks and balances in the governing system. EPRDF officials reportedly receive preferential access to credit, land leases and jobs.

Although the political system consists formally of an elected parliament based on (unfair) competition between several parties, Ethiopia must be regarded as a “facade democracy.” The legally elected institutions are in fact part of an authoritarian system that does not offer citizens a free choice between competing political parties. Since 2005, the government has harassed and imprisoned political opponents, journalists and members of the Muslim population.

Freedom in the World Index 2017 (FWI)

In the Freedom in the World Index, Ethiopia received an aggregate score of 12/100 (0=least free; 100=most free).

On “Freedom”, Ethiopia was rated 6.5/7; and on “Civil “Liberties” 6/7 (1=most free; 7=least free)

Freedom in the World is an annual survey “that measures the degree of civil liberties and political rights in every nation and significant related and disputed territories around the world.”

Multidimensional Poverty Index 2016 (MPI)

Ethiopia ranks 174 out of 185 countries on the MPI.

MPI defines poverty not only by income but a variety of other “factors that constitute poor people’s experience of deprivation – such as poor health, lack of education, inadequate living standard, lack of income (as one of several factors considered), disempowerment, poor quality of work and threat from violence.”

According to MPI, life expectancy in Ethiopia is 64.6 years. The expected years of schooling is reported at 8.4 years.

Ethiopia has a Geni coefficient of 33.2.

The Gini coefficient is a measure of inequality in society. (A Gini coefficient of zero expresses perfect equality, e.g. where everyone has the same income; and a Gini coefficient of 1 (or 100%) expresses maximal inequality among values).

On the gender development index, Ethiopia scores 0.842 and ranks 174/185.

The Ethiopian population living below the poverty line ($1.90 per day) was reported at 35.3% for 2005-2014.

The Ethiopian “population in severe multidimensional poverty” is a staggering 67%.

Freedom on the Net Index 2016 (FNI)

On the Freedom on the Net Index, Ethiopia’s overall score is 83/100 (0=most free; 100= least free).

Ethiopia is one of the least connected countries in the world with an internet penetration rate of only 12 percent, according to 2015 data from the International Telecommunications Union (ITU).

FNI reported, “A handful of signal stations service the entire country, resulting in network congestion and frequent disconnection. In a typical small town, individuals often hike to the top of the nearest hill to find a mobile phone signal.”

On obstacles to internet access, Ethiopia received a score of 23/25; limits on content 28/35 and violations of users rights 32/40.

Freedom House which publishes the FNI “assesses each country’s degree of political freedoms and civil liberties, monitor censorship, intimidation and violence against journalists, and public access to information.”

FNI noted, “The legal environment for internet freedom became more restrictive under the Computer Crime Proclamation enacted in June 2016, which criminalizes defamation and incitement. The proclamation also strengthens the government’s surveillance capabilities by enabling real-time monitoring or interception of communications.”

FNI reported that “authorities frequently shutdown local and national internet and mobile phone networks and social media to prevent citizens from communicating about the protests. The Ethiopian government’s monopolistic control over the country’s telecommunications infrastructure via EthioTelecom enables it to restrict information flows and access to internet and mobile phone services.”

Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index 2017 (RWBI)

Ethiopia ranked 150/180 with a score 50.34 on the RWBI.

The RWBI is based on a survey conducted by Reporters Without Borders covering issues of “freedom, pluralism, media independence, environment and self-censorship, legislative framework, transparency, infrastructure, penalties for press offences, existence of a state monopoly and other related factors.”

The RWBI reports that the regime in Ethiopia uses “terrorism charges to systematically silence the media.” Journalists are sentenced to long prison terms and the “anti-terrorism law” has been used to “hold journalists without trial for extended periods.” According to the RWBI, “there has been little improvement since the purges that led to the closure of six newspapers in 2014 and drove around 30 journalists into exile. Indeed, the state of emergency proclaimed in 2016 goes so far as to ban Ethiopians from looking at certain media outlets. Additionally, the Internet and social networks were often disconnected in 2016. Physical and verbal threats, arbitrary trials, and convictions are all used to silence the media.”

Freedom House Freedom of the Press 2017 (PHFP)

Ethiopia received a total score of 86/100 (0=Most Free, 100=Least Free) on the PHFP.

On the “legal environment” of the press, the score was 29/30. On “political environment”, the score was 38/40.

PHFP reported,

Ethiopia was the second-worst jailer of journalists in sub-Saharan Africa. Ethiopia’s media environment is one of the most restrictive in sub-Saharan Africa. The government of Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn continues to use the country’s harsh antiterrorism law and other legal measures to silence critical journalists and bloggers. As of December 2016, Ethiopia was detaining 16 journalists, making it the fifth-worst jailer of journalists in the world and the second-worst in sub-Saharan Africa, after Eritrea. In addition to the use of harsh laws, the government employs a variety of other strategies to maintain a stranglehold on the flow of information, including outright censorship of newspapers and the internet, arbitrary detention and intimidation of journalists and online writers, and heavy taxation on the publishing process.

What is the price of peace in Ethiopia?

Will Ethiopia go the way of peace thorugh atonement and reconciliation or take the path of civil war and bloodshed?

President John F. Kennedy warned that, “Those who make peaceful revolution impossible will make violent revolution inevitable.”

Nelson Mandela taught that the choice of violent revolution is exclusively in the hands of the oppressor and the oppressed merely imitate the oppressor in the choice of the means of struggle. Mandela explained (forward clip to 13:39 min.) in 2000:

The methods of political action which are used by the oppressed people are determined by the oppressor himself. If the oppressor uses dialogue, persuasion, talking to the other, the oppressed people will do precisely the same. But if the oppressor decides to tighten oppression and to resort to violence, what he is saying to the oppressed is if you want to change your method, your condition, do exactly what I am doing. So in many cases those people who are being condemned for violence are doing nothing else. They are replying, responding to what the oppressor is doing…. Generally speaking, it doesn’t mean that a person because a person believes that freedom comes through the barrel of a gun, that person is wrong. He is merely responding to the situation in which he and his community finds himself or herself. (Emphasis added.)

So, whether the future of Ethiopia will be decided by dialogue, persuasion and talking to each other or in a civil war is entirely in the hands of the T-TPLF.

My dream for Ethiopia is merely a reflection of Mandela’s dream for Africa: “I dream of an Africa which is in peace with itself. I dream of the realization of unity of Africa whereby its leaders, some of whom are highly competent and experienced, can unite in their efforts to improve and to solve the problems of Africa.”

Ethiopians united can never be defeated!!!

The time for peace, dialogue, persuasion and talking to each other in Ethiopia is NOW.

Or never!