I am celebrating the 800th anniversary of the Magna Carta Libertatum or the Great Charter of English Liberties.

I am celebrating the 800th anniversary of the Magna Carta Libertatum or the Great Charter of English Liberties.

Whoa! Hold it! I understand your question!

Why is a guy born in Africa (Ethiopia) now living in America celebrating a document written by a bunch of disgruntled and rebellious English barons quarrelling with a feudal monarch over taxes and restoration of their feudal privileges in Medieval England 800 years ago?

No, I do not like feudalism or monarchies. I grew up in feudal Ethiopia. I saw wretchedness, decadence and decay. The first government I ever knew was a monarchy. A swift stroke of the socialist sickle put that monarchy to eternal rest. For me, feudalism and monarchies are quaint anachronisms. I recall reading Karl Marx describing feudalism as the cradle of capitalism. In 1974, the impetuous and feckless junior officers in the Ethiopian military thought they could make a beeline to socialism from feudalism on the wings of martial law.

I am certainly not celebrating the Magna Carta because King John was a philosopher king. John was the consummate scoundrel. He was treacherous, traitorous, greedy and cruel. John was the kind of royal villain who “can smile as he murdered”. They said, “Hell itself is defiled by the fouler presence of King John.”

John was a vindictive tyrant. He arrested, detained and jailed his subjects at will. He exacted outrageous taxes to fill his coffers, sate his greed and wage war so he could enrich himself even more. His “scutage” tax (payment by a feudal landowner to be excused from military service or provide a knight) on the barons and “amercements” (fines) were elaborate extortion schemes.

John was so greedy that he dispossessed his subjects of their land, horses, carts, corn and wood without legal process. He used the Royal Forests as a major source of revenue and made it the citadel of corruption in his reign. He literally sold justice. Since the royal system of justice had complete jurisdiction over all matters in the kingdom, litigants were required to pay the monarch fees. Depending on the state of his cash flow at a particular moment, John would regularly sell legal rights and privileges to the highest bidder. John surrounded himself with mercenary thugs who fought his wars. He meddled in the affairs of religion. He was a power hungry power monger.

If my description of King John sounds like the average African dictator or thugtator of the 21st Century, the similarities are not that far-fetched. Today, from one end of Africa to the other, African dictator’s arrest, jail, harass and intimidate their opposition at will. African dictators use their kangaroo courts to persecute their opponents, subvert justice and even sell it to the highest bidder out in the open. They dispossess their poorest citizens of their forested ancestral lands, and hand over millions of hectares to foreign “investors” literally for pennies, which in turn burn down the forests to establish their commercial farms. They massacre their citizens who oppose them without raising arms. They jail, torture and exile their political opposition. They steal hundreds of millions of dollars from their people every year and fatten their foreign bank accounts. They meddle in religion and promote communal strife to cling to power. They are warmongers visiting death and destruction on their people. They commit crimes against humanity and genocide. At least two African “heads of state” have been indicted by the Prosecutor for the International Criminal Court. Like King John, African dictators “can smile as they murder” but they can also murder as they smile. ‘Tis true, Hell itself is defiled by the fouler presence of African dictators and thugtators.

Why am I celebrating the English Magna Carta?

To answer my own question, I have to go back some fifty years when I was a teenager in Ethiopia. I was a bookish type. I was very fortunate to have access to the great works of world literature and philosophy. I was quite familiar with the American literati of the 1960s. I also read popular works of fiction in Amharic.

I was most fascinated by the law. From a very young age, I was exposed to the world of litigation. I tagged along to observe court proceedings in the high courts in Addis Ababa and other courts in outlying areas. I remember vividly the legal scribes sitting under makeshift kiosks on the side streets outside the court compounds cranking out pleadings in exquisite Amharic penmanship with a Bic ballpoint pen. I enjoyed listening to silver-tongued lawyers and discerning judges talking and arguing points of law, particularly procedure, and not just in the courtroom. The eloquence of diction, cogency of arguments and spellbinding oratory of some of the lawyers and the razor sharp questions and incisive wit of the judges back then left a lifelong impression on me. They were great role models for me.

I read the Ethiopian Penal and Civil Codes in Amharic in bits and pieces, especially after listening to the lawyers and judges arguing about them. I especially liked criminal and civil procedure (sine sirat). The civil procedure code (Fitha Beher) was less than 245 pages bound in a small volume. The criminal procedure code was a mere 69 pages appended to the penal code. Neither was hard reading at all.

I was most fascinated by legal arguments over violations of procedural rules. Did the police investigate the alleged crime the right way? Was the arrest made on probable cause? Did the police preserve the evidence properly? Were the documents presented in a civil case properly authenticated? Is there sufficient basis to grant an injunction (Mageja)?

I still have my original collection of Ethiopian Codes to this day, one-half century later (see picture above). I now know that the criminal and civil procedural rules in the Codes were highly advanced even by today’s standards. True, oxidative degradation (aging) has taken a toll on my one-half century volumes. The paper is turning yellow and the glue on the spine of those volumes dried out and separated long ago; but I still peruse the Codes from time to time to marvel at how modern and advanced those procedures were.

Thirty years later, I had my chance to stand up for one of the greatest procedural protections of the American people in the California Supreme Court, the right against self-incrimination guaranteed in the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. As I walked the steps of that Court in Sacramento, CA for oral argument, I looked up at the imposing Ionic columns and for a brief moment remembered the great lawyers and judges in my childhood, and I smiled.

There was also H.I.M. Haile Selassie’s 1955 Revised Ethiopian Constitution. I never witnessed a constitutional argument in any case I observed in court, or any discussion of it outside of court. I occasionally heard learned judges and lawyers referring to “The Constitution” (Hige Mengist) from time to time, but none of their discussions registered or resonated in my mind.

As I studied that Constitution over the years, I became fascinated by the uncanny similarity of Chapter III to the American Bill of Rights. Chapter III could be described as the “Ethiopian Bill of Rights”. H.I.M. Haile Selassie’s adoption of such broad liberties for his subjects even in principle testifies to some irrepressible modernizing impulse he cherished at the core of his extreme political conservatism as a monarch. Yet, few enjoyed those constitutional liberties. Like most monarchs in history, H.I.M. outlived his usefulness.

I would wager to say Chapter III of the 1955 Revised Constitution of Ethiopia, with a few exceptions, is a virtual carbon copy of the American Bill of Rights and other amendments to the U.S. Constitution:

No one shall be denied the equal protection of the laws… No one within the Empire may be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law… No one may be deprived of his property except… by judicial procedures established by law… Ethiopian subjects shall have the right to assemble peaceably… No one may be arrested without a warrant issued by a court… Every arrested person shall be brought before the judicial authority within forty-eight hours of his arrest… In all criminal prosecutions the accused… shall have the right to a speedy trial and to be confronted with the witnesses against him, to have compulsory process… for obtaining witnesses in his favor at the expense of the Government and to have the assistance of a counsel for his defense [at government expense]. (It was not until 1963 that poor defendants in the United States got the right to government-appointed counsel in state criminal prosecutions, 8 years after it was guaranteed in the Imperial Constitution.) No person accused of and arrested for a crime shall be presumed guilty until so proved…. No one shall be punished twice for the same offence… No one shall be subjected to cruel and inhuman punishment… All persons and all private domiciles shall be exempt from unlawful searches and seizures… no one shall have the right to bring suit against the Emperor… No one within the Empire may be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law… The present revised Constitution… shall be the supreme law of the Empire…

The 1994 Ethiopian Constitution of the Tigrean Peoples Liberation Front (TPLF) is equally beneficent in words with its grant of liberties and freedoms. Under Chapter III “HUMAN RIGHTS” are listed the following liberties which virtually replicate the American Bill of Rights:

No one shall be deprived of his liberty except in accordance with such procedures as are laid down by law…. arrested or detained without being charged or convicted of a crime except in accordance with [due process]… Everyone shall have the right not to be subjected to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. Anyone arrested on criminal charges shall have the right to be informed promptly and in detail… of the nature and cause of the charge against him. Everyone shall have the right to keep silent and be warned promptly [and] that any statement he may make may be used in evidence against him. Everyone shall have the right to be brought before a court of law within 48 hours after his arrest. Everyone shall be entitled to an inalienable right of habeas corpus… Anyone arrested shall have the right to be released on bail. Everyone charged with an offence shall be entitled to a public hearing before an ordinary court of law without undue delay… Everyone charged with an offence shall be adequately informed in writing of the charges brought against him. Everyone charged with an offence shall have the right to defend himself through legal assistance of his own choosing and to have free legal assistance assigned to him by the government… [The] Constitution is the supreme law of the land….

The TPLF copied and pasted much of the American Bill of Rights into its constitution and promptly shredded it into pieces.

Where did H.I.M. Haile Selassie get his ideas about civil liberties and personal freedoms in the 1955 Revised Ethiopian Constitution?

Where did the Tigrean Peoples Liberation Front get its ideas about civil liberties and personal freedoms in its 1994 Constitution?

There is no question that H.I.M. Haile Selassie adopted the bulk of the American Bill of Rights right down to the phraseology as highlighted above.

There is also no question the Tigrean Peoples Liberation Front got its ideas about civil liberties and personal freedoms from the 1955 Revised Ethiopian Constitution.

So, the $64 thousand dollar question is: Where did the Americans get many of their ideas about important individual liberties and freedoms?

They got it from the Magna Carta. The enumerated liberties in the American Bill of Rights (the first ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution) dealing with freedom of petition (1st amendment), due process of law (5th and 14th amendments) which covers a whole slew of individual liberties, taking and just compensation (5th amendment), neutral magistrate (4th amendment), no excessive bails and fines (8th amendment), speedy public trials, confrontation of accusers, jury trial and impartial jury (6th amendment), supreme law of the land (Art. VI), writ of habeas corpus (Article I, Section IX), as well as freedom of travel and of privacy and other rights have their origins in the Magna Carta.

There lies my answer to my question. I am celebrating the Magna Carta because a good part our DNA for constitutional liberties and freedoms as Ethiopians trace its lineage to the Magna Carta. This fact may come as a surprise to some; but it is undeniable that the genotype of Ethiopian constitutional liberties carries with it the inherited instructions of the genetic code of the Magna Carta. However, I do not believe that heritage or lineage is unique to Ethiopia. The phenotype of every modern constitution that aspires and pledges to protect individual liberties may be different, but all can trace their genotypes directly to the Magna Carta.

What is Magna Carta?

The Magna Carta was the first legal document drafted by the ruled and imposed on the rulers. It is the first bold effort by the ruled to subjugate their rulers to the rule of law. It is the first effort undertaken to create a binding political contract between the rulers and the ruled, with the ruled writing the rules and securing for themselves and their posterity specific written guarantees of liberties and property protections. Of course, the document was tailored for English baron of freeholders against the exercise of royal arbitrary power.

There have been great legal codes before the Magna Carta beginning with the Ten Commandments. The Code of Justinian assembled collections of laws and legal interpretations of the Roman jurists. The Romans also made the law accessible to the plebeians by recording it in the Twelve Tables and posting it in the Roman Forum so that the plebeians are aware of their rights and protect themselves against abuse of power by the patricians. Solon’s Laws aimed to resolve conflict between the landed aristocracy and peasantry in ancient Athens. Solon’s Laws made it possible for any Athenian, not just a wronged party, to initiate a lawsuit. It also established an appellate process for review of the decisions of the magistrates to a court of the citizens at large. The Hammurabic Code of ancient Babylon consisted of 282 laws dealing with a whole range of issues including household and family matters, civil liability and even military service. That Code is today remembered for its draconian punishment of “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth”.

None of the legal documents preceding the Magna Carta were predicated on the principle of the rule of law. None of the laws originated in the sovereignty of the common people nor were they enacted with their consent. The common people had little say in the making of the laws that were imposed upon them. They were expected to obey and follow the laws and live out their miserable lives in quiet desperation. The commoners never dared to impose limits on the powers of their rulers.

Prior to the Magna Carta, King John and his royal predecessors had ruled using the principle of vis et voluntas (“force and will”). John did whatever he wanted because he believed as the king he was above the law and accountable to no earthly power (save perhaps the Holy See). It was a generally accepted fact of medieval English politics that English monarchs should rule in accordance with the prevailing social customs and the common law (judgment and decrees of the courts) aided by the able counsel of the leading members of the kingdom. John’s predecessor Henry II in fact had introduced functional legal procedures which provided protections against deprivation of property without legal process.

The question was what to do if the king disregarded his own laws, the laws of his predecessors, ignored custom and simply refused to be bound by a judicial decree or anything else?

Such was the problem the barons had with King John in the years preceding 1215. John was dismissive and oppressive of the barons. He waged war on them. He sent bailiffs to jail them without evidence or proof of wrongdoing. He demanded feudal payments and taxes from them. He refused to comply with his own laws and shunned the existing legal process.

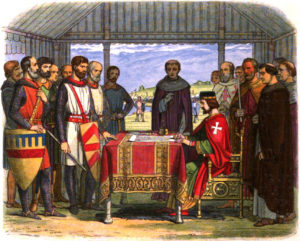

The barons wanted restraints on John’s arbitrary powers. They wanted him to abide by his own laws and the customs of the land. In June 1215, a group of angry armed barons showed up at Runnymede, a water-meadow alongside the River Thames, not far from London to “discuss” their grievances with King John. They were actually there to deliver an ultimatum to John: Stop your tyrannical ways or prepare to deal with a rebellion and most likely civil war.

John was in no position to negotiate. He had recently suffered an ignominious defeat following his invasion of France. The barons bore the financial burdens of paying for John’s mercenary army by paying “scutage”. They had no interest in John’s feud with the French king and would not support him. John had lashed out against the barons for their refusal to support his military adventures. John’s negotiating position had also been weakened by his ongoing problems with Pope Innocent III in Rome as early as 1208. His attempts to interfere in the appointment of bishops and meddle in the church’s financial affairs earned him a papal excommunication in 1209.

The rebellious barons who showed up at Runnymede in June 1215 were not happy campers. A month earlier, they had taken control of London and felt they had a strong negotiating hand. They had their Articles of the Barons drafted and all they needed was John’s signature. There was not much left for John to wheel and deal. The “negotiations” concluded on June 15, 1215 when King John reluctantly affixed his royal seal on the Magna Carta. John averted a civil war and made peace with his rebellious barons and regained their allegiance.

Although John signed the Magna Carta, he had no intention of upholding its terms despite his express agreement to do so “in good faith and without any evil intention” (Cl. 63).

Within weeks, the Magna Carta agreement was unravelling. John was particularly bothered by the provision dealing with implementation of the Magna Carta. He found clause 61, the security clause, particularly odious. In that clause, he felt he had given away the royal store of power. He had conceded that “the barons shall choose any twenty-five barons of the realm as they wish, who with all their might are to observe, maintain and cause to be observed the peace and liberties which we have granted”. He had effectively brought himself under baronial supervision and monitoring. Clause 61 was a clever move by the barons because they knew John was a snake in the grass.

John did not disappoint. He sent messengers to the Pope in the summer of 1215 requesting annulment of the Magna Carta. The barons struck back by refusing to give up the city of London unless and until John implemented the Magna Carta. In August 1215, Pope Innocent III issued a “papal bull” (an official letter with a seal “bulla”) declaring the Magna Carta “illegal, unjust, harmful to royal rights and shameful to the English people”, and “null and void of all validity forever”.

In September 1215, civil war broke out between King John and his barons. As usual, John enlisted his army of mercenaries to fight the barons. The barons in turn invited the heir to the French throne to come and become king. The French invaded England in 1216. John died of dysentery during that war.

Henry III succeeded John to the throne at age 9. In November 1216, a revised version of the Magna Carta was issued to regain the loyalty and support of the barons. In 1217, yet another version of the Magna Carta was granted after the expulsion of the French. When Henry reached the age of 18, he issued a significantly revised version which was enrolled on the statute book by King Edward I in 1297.

What is in the Magna Carta of 1215?

The Magna Carta is a document of extraordinary insight, foresight and breadth in terms of its articulation of “English liberties.”

It covers a variety of issues ranging from methods of lodging specific grievances regarding land ownership to the regulation of the justice system, taxes (“scutage” and “socage” [periodic payments for using land], and removal of fish from various rivers and standardization of various weights and measures and so on.

The most notable clauses (Cl.) of the Magna Carta spell out the nature of “English liberties” and resonate to the present day through multitudes of modern constitutions and international human rights treaties and conventions.

In the 1215 Magna Carta, King John agreed to recognize and accept a whole slew of liberties guaranteed to his subjects (barons) that are stunning by the standards of any age. Specifically, he agreed to

- observe the Charter and the liberties set forth therein of his “own free will with good faith and [to bind his] heirs forever” (Cl.1);

- impose “no scutage (taxes) unless by the common council of our kingdom (Cl. 12);

- that “Common Pleas [ordinary lawsuits] [so that they] shall not follow our court, but shall be held in a fixed place” (Cl. 17);

- exempt “A free-man [from being] amerced [given an arbitrary fine] for a small offence… (Cl. 20);

- prohibit his “sheriffs, constables, coroners, [and] bailiffs [from] holding

- pleas of [which should be dealt with by] our Crown” (Cl. 24);

- prohibit his “constables and bailiffs [from] taking the corn or other goods of any one, without instantly paying money for them” (Cl. 28); or “tak[ing] the horses or carts of any free-man without the consent of the said free-man (Cl. 29); or “tak[ing] another man’s wood, for our castles or other uses” (Cl. 31);

• terminate use of the ‘writ of præcipe [order to show cause] by which a free-man may lose his court [right of trial in his own lord’s court]” (Cl. 34).

• prohibit the practice in which a “ bailiff shall put any man to his law, upon his own simple affirmation, without credible witnesses produced for that purpose” (Cl. 38);

- stop the practice of “seizing, imprisoning, dispossessing, outlawing, condemning or committing to prison any free man except by the legal

• judgment of his peers, or by the laws of the land” (Cl. 39);

- not to “sell, deny, or delay right or justice” (Cl. 40);

- guarantee that it “shall be lawful to any person to go out of our kingdom, and to return, safely and securely (Cl. 42);

- appoint only “justiciaries, constables, sheriffs, or bailiffs [unless they] know the laws of the land, and are well disposed to observe them” (Cl. 45);

- compensate and make “immediate” restitution to those who have been “disseised [wrongfully removed from possession of property] or dispossessed by us, without a legal verdict of their peers, of their lands, castles, liberties, or rights” (Cl. 52);

- make restitution of “all fines that have been made by us unjustly, or contrary to the laws of the land; and all amercements [fines] that have been imposed unjustly, or contrary to the laws of the land” (Cl. 55);

- agreed to the appointment of “twenty-five barons [elected freely] who shall with their whole power, observe, keep, and cause to be observed, the peace and liberties which we have granted to them [in the Magna Carta] (Cl. 61).

The Magna Carta also included un-libertarian terms. It provided that, “no man shall be apprehended or imprisoned on the appeal of a woman, for the death of any other man except her husband” (Cl. 54). A widow could not be “compelled to marry, so long as she wishes to remain without a husband. But she must give security that she will not marry without royal consent (Cl. 8). Six hundred years later, the British philosopher John Stuart Mills wrote, “I consider it presumption in anyone to pretend to decide what women are or are not, can or cannot be, by natural constitution. They have always hitherto been kept, as far as regards spontaneous development, in so unnatural a state, that their nature cannot but have been greatly distorted and disguised…” American women got the constitutional right to vote in 1920. There are still countries in the world in the second decade of the 21st Century where women do not have the right to vote.

The Magna Carta also included a streak of the millennia-old bigotry against Jews. It provided, “If anyone has borrowed anything from the Jews and die before that debt be paid, the debt shall pay no interest so long as his heir shall be under age… And if any one shall die indebted to the Jews, his wife shall have her dower and shall pay nothing of that debt…” (Cls. 10, 11.)

Although the 1215 Magna Carta contained 63 clauses when it was first granted, only a few remain part of English law today. In 1969, the Statute Law (Repeals) Act repealed almost all of the 1225 Magna Carta, except Clauses 1, 9, 29. It has also been superseded by the Human Rights Act of 1998.

The legacy of the Magna Carta as I see it

Learned scholars, lawyers, judges and others will continue to argue about the relevance and significance of the Magna Carta for another 800 years. Did the Magna Carta give all persons in the kingdom or just the “free barons” the right to justice and a fair trial? Did it have any relevance to the unfree peasants (“villeins”) who had to apply to their own lords for justice? Did the Magna Carta guarantee the right to trial by jury? Establish the supremacy of the principle of the rule of law? Institutionalize the due process of law? Did it establish for the very first time a constitutional framework (social contract) between government and citizens? Make practical the idea of individual liberty? Institutionalize the principle of the law of the land to which all (including kings, prime ministers, presidents, congresses, parliaments, etc.,) must submit?

Despite scholarly disagreements, there is substantial consensus that the Magna Carta inspired the framers of the American Constitution (1787) and the drafters of the American Bill of Rights [first ten amendments] (1791) in their quintessential pursuit to limit the arbitrary exercise of governmental power. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights [UDHR] (1948), which has been signed by virtually every country from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe also reflects the text and spirit of the Magna Carta. When Eleanor Roosevelt chaired the committee that drafted the UDHR, she dreamt of a “common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations” with respect to equality, dignity and rights. I agree with her. I do not believe there is Ethiopian “rights”, American “rights”, English “rights”, Chinese “rights”, Egyptian “rights”… I believe there is only human rights.

For me, a dyed-in-the-wool and unapologetic Ethiopian- American constitutional lawyer and scholar, the Magna Carta has enormous symbolic appeal. I understand the Magna Carta as a quintessentially procedural legal document predicated on the twin principles of government accountability and transparency. Those who exercise power shall be held accountable under the supreme law of the land for their actions and omissions by a set of rules and standards. The relationship between the rulers and the ruled must be strictly regulated by a set of clear procedures. No ruler shall have the power to deprive any citizen of life liberty or property without due process of law. I believe the Magna Carta is the first constitutional document in human history to put the brakes on the arbitrary exercise of power and shield individual liberty from the vagaries and capriciousness of those corrupted by power.

William Gladstone who served as British Prime Minister on four separate occasions in the 19th Century, mindful of the Magna Carta observed, “As the British Constitution is the most subtle organism which has proceeded from the womb and the long gestation of progressive history, so the American Constitution is, so far as I can see, the most wonderful work ever struck off at a given time by the brain and purpose of man.” ‘Tis true that imperfect Constitution which turned a blind eye to slavery, is, undoubtedly, a work of extraordinary collective genius.

My view of liberty is a very simple one. I believe liberty predates government. I do not believe government can “grant” rights and freedoms to its citizens. Government, being the collective invention of citizens, exists only to protect the lives, liberties and properties of its citizens.

I have this wacky way of explaining my views on the relationship between government and citizens. I regard government as a watchdog (almost literally) for its masters, the people. (Pardon me if I sound like I am maligning man’s and woman’s best friend with my descriptive metaphor. ) The only function of this watchdog is to protect the lives, liberties and properties of its masters. This watchdog is naturally treacherous and must be watched at all times with eagle eyes and extreme vigilance by its masters. This watchdog has an inbred and ineradicable trait of always turning against its masters unless it is held tightly on a very short chain leash. The constitution is the chain leash on the “government dog”. The shorter the leash, the better and safer it is for the dog’s masters. Thomas Jefferson aptly observed, “When government fears the people, there is liberty. When the people fear the government, there is tyranny.” The government exists to serve the people, not the other way around. The masters of the dog should never fear the dog.

That is why I believe all government officials, leaders, institutions and anyone exercising power should be chained at all times with the “supreme law” of the land, placed under eternal vigilance and held strictly accountable for their actions and omissions. James Madison, one of the foremost framers of the American Constitution wrote, “If men were angels, no government would be necessary.” I would say if governments did not degenerate into demons, men and women could bring out their best and aspire to be angels.

I wholeheartedly agree with John Adams, the second president of the United States who observed, “There is danger from all men [and women]. The only maxim of a free government ought to be to trust no man [or woman] living with power to endanger the public liberty.”

President Dwight D. Eisenhower warned, “The clearest way to show what the rule of law means to us in everyday life is to recall what has happened when there is no rule of law.” Could he have been foretelling the present fate of Africa?

On July 28, 2014, President Obama told a town hall meeting of Young African Leaders, “Regardless of the resources a country possesses, regardless of how talented the people are, if you do not have a basic system of rule of law, of respect for civil rights and human rights, if you do not give people a credible, legitimate way to work through the political process to express their aspirations, if you don’t respect basic freedom of speech and freedom of assembly … it is very rare for a country to succeed.”

Ethiopia needs to succeed as a nation and as a people. Africa needs to succeed as a continent. Today, Ethiopia is in its end stage of becoming a completely failed state. So are many other African countries. I doubt there is a single, not one, African state that would not collapse within days (not weeks) but for Western charity and loans. Contemporary African regimes exist because they are bankrolled by the tax dollars of the Western countries. That is such a bitter pill to swallow!

Over the past five years, cynicism and pessimism have whittled down my hopes and dreams for the rule of law and a peaceful transition to multiparty democracy in Africa. Every day I ask myself, “Is there any hope for Africa?” For Ethiopia? Does Africa’s destiny hang in the balance between the audacity of hope and the rapacity of despair? Is Africa condemned to a future of civil wars, genocides, anarchy, lawlessness and crimes against humanity? Does Africa’s best hope hang on the strings attached to its multilateral loans and aid? Will Africa be buried under a mountain of international debt while predatory foreign investors officiate at its funeral? Is Africa doomed to become the permanent object of charity, sympathy and pity for the rest of the world? Is Africa floating on a turbulent sea of hope or drowning in an ocean of despair? Is there something buried deeply in the African ethos (character), logos (logic of the African mind), pathos (spirit/soul) and bathos (African narrative of the trivial into the sublime) that makes Africans extremely susceptible to the triple deadly cancers of brutality, despotism and corruption? Is Africa the infernal stage of Dante’s “divine comedy”?: “Abandon all hope, you who enter [live] here [in Africa].”

I am sure there will be some among my readership who would question and even criticize me for joyfully celebrating the Magna Carta. After all, it is a document of white people. (I have got to tell the truth!) It is the founding document of the wicked colonial oppressors and the rest of it. The Magna Carta could not possibly have relevance to Black, Brown, Yellow and, yes, Green people. With the exception of Green people, I ask the rest to look at their own constitutions. I would like to ask them where the liberties enshrined in their dusty constitutions originated. I would be glad to know which one of their liberties they are willing to surrender to their governments.

Elie Weisel said, “Just as man cannot live without dreams, he cannot live without hope. If dreams reflect the past, hope summons the future.” So I have chosen to dream about the path of hope – the rule of law administered through a competent independent judiciary to promote freedom, justice and equality– for Ethiopia and the African continent and forswear the path of despair. It is not easy to hope and dream when an entire continent is enveloped and trapped in a long night of dictatorship and oppression. It is in such melancholy state that I find myself reflecting on the words of Henry Francis Lyte:

Swift to its close ebbs out life’s little day;

Earth’s joys grow dim, its glories pass away;

Change and decay in all around I see:

O thou who changest not, abide with me!

I must confess to my readers the great sadness I feel as I conclude this joyful commentary on the Magna Carta.

I am deeply, deeply pained by the irony that I can freely celebrate and cherish an English charter of liberties written 800 years ago which is not even law today, yet I cannot do the same for the Ethiopian Constitution written only twenty years ago to usher a new era of freedom, justice and equality because it is not worth the paper it is written on!

Whoa! Hold it! I understand your question!

Why is a guy born in Africa (Ethiopia) now living in America celebrating a document written by a bunch of disgruntled and rebellious English barons quarrelling with a feudal monarch over taxes and restoration of their feudal privileges in Medieval England 800 years ago?

No, I do not like feudalism or monarchies. I grew up in feudal Ethiopia. I saw wretchedness, decadence and decay. The first government I ever knew was a monarchy. A swift stroke of the socialist sickle put that monarchy to eternal rest. For me, feudalism and monarchies are quaint anachronisms. I recall reading Karl Marx describing feudalism as the cradle of capitalism. In 1974, the impetuous and feckless junior officers in the Ethiopian military thought they could make a beeline to socialism from feudalism on the wings of martial law.

I am certainly not celebrating the Magna Carta because King John was a philosopher king. John was the consummate scoundrel. He was treacherous, traitorous, greedy and cruel. John was the kind of royal villain who “can smile as he murdered”. They said, “Hell itself is defiled by the fouler presence of King John.”

John was a vindictive tyrant. He arrested, detained and jailed his subjects at will. He exacted outrageous taxes to fill his coffers, sate his greed and wage war so he could enrich himself even more. His “scutage” tax (payment by a feudal landowner to be excused from military service or provide a knight) on the barons and “amercements” (fines) were elaborate extortion schemes.

John was so greedy that he dispossessed his subjects of their land, horses, carts, corn and wood without legal process. He used the Royal Forests as a major source of revenue and made it the citadel of corruption in his reign. He literally sold justice. Since the royal system of justice had complete jurisdiction over all matters in the kingdom, litigants were required to pay the monarch fees. Depending on the state of his cash flow at a particular moment, John would regularly sell legal rights and privileges to the highest bidder. John surrounded himself with mercenary thugs who fought his wars. He meddled in the affairs of religion. He was a power hungry power monger.

If my description of King John sounds like the average African dictator or thugtator of the 21st Century, the similarities are not that far-fetched. Today, from one end of Africa to the other, African dictator’s arrest, jail, harass and intimidate their opposition at will. African dictators use their kangaroo courts to persecute their opponents, subvert justice and even sell it to the highest bidder out in the open. They dispossess their poorest citizens of their forested ancestral lands, and hand over millions of hectares to foreign “investors” literally for pennies, which in turn burn down the forests to establish their commercial farms. They massacre their citizens who oppose them without raising arms. They jail, torture and exile their political opposition. They steal hundreds of millions of dollars from their people every year and fatten their foreign bank accounts. They meddle in religion and promote communal strife to cling to power. They are warmongers visiting death and destruction on their people. They commit crimes against humanity and genocide. At least two African “heads of state” have been indicted by the Prosecutor for the International Criminal Court. Like King John, African dictators “can smile as they murder” but they can also murder as they smile. ‘Tis true, Hell itself is defiled by the fouler presence of African dictators and thugtators.

Why am I celebrating the English Magna Carta?

To answer my own question, I have to go back some fifty years when I was a teenager in Ethiopia. I was a bookish type. I was very fortunate to have access to the great works of world literature and philosophy. I was quite familiar with the American literati of the 1960s. I also read popular works of fiction in Amharic.

I was most fascinated by the law. From a very young age, I was exposed to the world of litigation. I tagged along to observe court proceedings in the high courts in Addis Ababa and other courts in outlying areas. I remember vividly the legal scribes sitting under makeshift kiosks on the side streets outside the court compounds cranking out pleadings in exquisite Amharic penmanship with a Bic ballpoint pen. I enjoyed listening to silver-tongued lawyers and discerning judges talking and arguing points of law, particularly procedure, and not just in the courtroom. The eloquence of diction, cogency of arguments and spellbinding oratory of some of the lawyers and the razor sharp questions and incisive wit of the judges back then left a lifelong impression on me. They were great role models for me.

I read the Ethiopian Penal and Civil Codes in Amharic in bits and pieces, especially after listening to the lawyers and judges arguing about them. I especially liked criminal and civil procedure (sine sirat). The civil procedure code (Fitha Beher) was less than 245 pages bound in a small volume. The criminal procedure code was a mere 69 pages appended to the penal code. Neither was hard reading at all.

I was most fascinated by legal arguments over violations of procedural rules. Did the police investigate the alleged crime the right way? Was the arrest made on probable cause? Did the police preserve the evidence properly? Were the documents presented in a civil case properly authenticated? Is there sufficient basis to grant an injunction (Mageja)?

I still have my original collection of Ethiopian Codes to this day, one-half century later (see picture above). I now know that the criminal and civil procedural rules in the Codes were highly advanced even by today’s standards. True, oxidative degradation (aging) has taken a toll on my one-half century volumes. The paper is turning yellow and the glue on the spine of those volumes dried out and separated long ago; but I still peruse the Codes from time to time to marvel at how modern and advanced those procedures were.

Thirty years later, I had my chance to stand up for one of the greatest procedural protections of the American people in the California Supreme Court, the right against self-incrimination guaranteed in the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. As I walked the steps of that Court in Sacramento, CA for oral argument, I looked up at the imposing Ionic columns and for a brief moment remembered the great lawyers and judges in my childhood, and I smiled.

There was also H.I.M. Haile Selassie’s 1955 Revised Ethiopian Constitution. I never witnessed a constitutional argument in any case I observed in court, or any discussion of it outside of court. I occasionally heard learned judges and lawyers referring to “The Constitution” (Hige Mengist) from time to time, but none of their discussions registered or resonated in my mind.

As I studied that Constitution over the years, I became fascinated by the uncanny similarity of Chapter III to the American Bill of Rights. Chapter III could be described as the “Ethiopian Bill of Rights”. H.I.M. Haile Selassie’s adoption of such broad liberties for his subjects even in principle testifies to some irrepressible modernizing impulse he cherished at the core of his extreme political conservatism as a monarch. Yet, few enjoyed those constitutional liberties. Like most monarchs in history, H.I.M. outlived his usefulness.

I would wager to say Chapter III of the 1955 Revised Constitution of Ethiopia, with a few exceptions, is a virtual carbon copy of the American Bill of Rights and other amendments to the U.S. Constitution:

No one shall be denied the equal protection of the laws… No one within the Empire may be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law… No one may be deprived of his property except… by judicial procedures established by law… Ethiopian subjects shall have the right to assemble peaceably… No one may be arrested without a warrant issued by a court… Every arrested person shall be brought before the judicial authority within forty-eight hours of his arrest… In all criminal prosecutions the accused… shall have the right to a speedy trial and to be confronted with the witnesses against him, to have compulsory process… for obtaining witnesses in his favor at the expense of the Government and to have the assistance of a counsel for his defense [at government expense]. (It was not until 1963 that poor defendants in the United States got the right to government-appointed counsel in state criminal prosecutions, 8 years after it was guaranteed in the Imperial Constitution.) No person accused of and arrested for a crime shall be presumed guilty until so proved…. No one shall be punished twice for the same offence… No one shall be subjected to cruel and inhuman punishment… All persons and all private domiciles shall be exempt from unlawful searches and seizures… no one shall have the right to bring suit against the Emperor… No one within the Empire may be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law… The present revised Constitution… shall be the supreme law of the Empire…

The 1994 Ethiopian Constitution of the Tigrean Peoples Liberation Front (TPLF) is equally beneficent in words with its grant of liberties and freedoms. Under Chapter III “HUMAN RIGHTS” are listed the following liberties which virtually replicate the American Bill of Rights:

No one shall be deprived of his liberty except in accordance with such procedures as are laid down by law…. arrested or detained without being charged or convicted of a crime except in accordance with [due process]… Everyone shall have the right not to be subjected to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. Anyone arrested on criminal charges shall have the right to be informed promptly and in detail… of the nature and cause of the charge against him. Everyone shall have the right to keep silent and be warned promptly [and] that any statement he may make may be used in evidence against him. Everyone shall have the right to be brought before a court of law within 48 hours after his arrest. Everyone shall be entitled to an inalienable right of habeas corpus… Anyone arrested shall have the right to be released on bail. Everyone charged with an offence shall be entitled to a public hearing before an ordinary court of law without undue delay… Everyone charged with an offence shall be adequately informed in writing of the charges brought against him. Everyone charged with an offence shall have the right to defend himself through legal assistance of his own choosing and to have free legal assistance assigned to him by the government… [The] Constitution is the supreme law of the land….

The TPLF copied and pasted much of the American Bill of Rights into its constitution and promptly shredded it into pieces.

Where did H.I.M. Haile Selassie get his ideas about civil liberties and personal freedoms in the 1955 Revised Ethiopian Constitution?

Where did the Tigrean Peoples Liberation Front get its ideas about civil liberties and personal freedoms in its 1994 Constitution?

There is no question that H.I.M. Haile Selassie adopted the bulk of the American Bill of Rights right down to the phraseology as highlighted above.

There is also no question the Tigrean Peoples Liberation Front got its ideas about civil liberties and personal freedoms from the 1955 Revised Ethiopian Constitution.

So, the $64 thousand dollar question is: Where did the Americans get many of their ideas about important individual liberties and freedoms?

They got it from the Magna Carta. The enumerated liberties in the American Bill of Rights (the first ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution) dealing with freedom of petition (1st amendment), due process of law (5th and 14th amendments) which covers a whole slew of individual liberties, taking and just compensation (5th amendment), neutral magistrate (4th amendment), no excessive bails and fines (8th amendment), speedy public trials, confrontation of accusers, jury trial and impartial jury (6th amendment), supreme law of the land (Art. VI), writ of habeas corpus (Article I, Section IX), as well as freedom of travel and of privacy and other rights have their origins in the Magna Carta.

There lies my answer to my question. I am celebrating the Magna Carta because a good part our DNA for constitutional liberties and freedoms as Ethiopians trace its lineage to the Magna Carta. This fact may come as a surprise to some; but it is undeniable that the genotype of Ethiopian constitutional liberties carries with it the inherited instructions of the genetic code of the Magna Carta. However, I do not believe that heritage or lineage is unique to Ethiopia. The phenotype of every modern constitution that aspires and pledges to protect individual liberties may be different, but all can trace their genotypes directly to the Magna Carta.

What is Magna Carta?

The Magna Carta was the first legal document drafted by the ruled and imposed on the rulers. It is the first bold effort by the ruled to subjugate their rulers to the rule of law. It is the first effort undertaken to create a binding political contract between the rulers and the ruled, with the ruled writing the rules and securing for themselves and their posterity specific written guarantees of liberties and property protections. Of course, the document was tailored for English baron of freeholders against the exercise of royal arbitrary power.

There have been great legal codes before the Magna Carta beginning with the Ten Commandments. The Code of Justinian assembled collections of laws and legal interpretations of the Roman jurists. The Romans also made the law accessible to the plebeians by recording it in the Twelve Tables and posting it in the Roman Forum so that the plebeians are aware of their rights and protect themselves against abuse of power by the patricians. Solon’s Laws aimed to resolve conflict between the landed aristocracy and peasantry in ancient Athens. Solon’s Laws made it possible for any Athenian, not just a wronged party, to initiate a lawsuit. It also established an appellate process for review of the decisions of the magistrates to a court of the citizens at large. The Hammurabic Code of ancient Babylon consisted of 282 laws dealing with a whole range of issues including household and family matters, civil liability and even military service. That Code is today remembered for its draconian punishment of “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth”.

None of the legal documents preceding the Magna Carta were predicated on the principle of the rule of law. None of the laws originated in the sovereignty of the common people nor were they enacted with their consent. The common people had little say in the making of the laws that were imposed upon them. They were expected to obey and follow the laws and live out their miserable lives in quiet desperation. The commoners never dared to impose limits on the powers of their rulers.

Prior to the Magna Carta, King John and his royal predecessors had ruled using the principle of vis et voluntas (“force and will”). John did whatever he wanted because he believed as the king he was above the law and accountable to no earthly power (save perhaps the Holy See). It was a generally accepted fact of medieval English politics that English monarchs should rule in accordance with the prevailing social customs and the common law (judgment and decrees of the courts) aided by the able counsel of the leading members of the kingdom. John’s predecessor Henry II in fact had introduced functional legal procedures which provided protections against deprivation of property without legal process.

The question was what to do if the king disregarded his own laws, the laws of his predecessors, ignored custom and simply refused to be bound by a judicial decree or anything else?

Such was the problem the barons had with King John in the years preceding 1215. John was dismissive and oppressive of the barons. He waged war on them. He sent bailiffs to jail them without evidence or proof of wrongdoing. He demanded feudal payments and taxes from them. He refused to comply with his own laws and shunned the existing legal process.

The barons wanted restraints on John’s arbitrary powers. They wanted him to abide by his own laws and the customs of the land. In June 1215, a group of angry armed barons showed up at Runnymede, a water-meadow alongside the River Thames, not far from London to “discuss” their grievances with King John. They were actually there to deliver an ultimatum to John: Stop your tyrannical ways or prepare to deal with a rebellion and most likely civil war.

John was in no position to negotiate. He had recently suffered an ignominious defeat following his invasion of France. The barons bore the financial burdens of paying for John’s mercenary army by paying “scutage”. They had no interest in John’s feud with the French king and would not support him. John had lashed out against the barons for their refusal to support his military adventures. John’s negotiating position had also been weakened by his ongoing problems with Pope Innocent III in Rome as early as 1208. His attempts to interfere in the appointment of bishops and meddle in the church’s financial affairs earned him a papal excommunication in 1209.

The rebellious barons who showed up at Runnymede in June 1215 were not happy campers. A month earlier, they had taken control of London and felt they had a strong negotiating hand. They had their Articles of the Barons drafted and all they needed was John’s signature. There was not much left for John to wheel and deal. The “negotiations” concluded on June 15, 1215 when King John reluctantly affixed his royal seal on the Magna Carta. John averted a civil war and made peace with his rebellious barons and regained their allegiance.

Although John signed the Magna Carta, he had no intention of upholding its terms despite his express agreement to do so “in good faith and without any evil intention” (Cl. 63).

Within weeks, the Magna Carta agreement was unravelling. John was particularly bothered by the provision dealing with implementation of the Magna Carta. He found clause 61, the security clause, particularly odious. In that clause, he felt he had given away the royal store of power. He had conceded that “the barons shall choose any twenty-five barons of the realm as they wish, who with all their might are to observe, maintain and cause to be observed the peace and liberties which we have granted”. He had effectively brought himself under baronial supervision and monitoring. Clause 61 was a clever move by the barons because they knew John was a snake in the grass.

John did not disappoint. He sent messengers to the Pope in the summer of 1215 requesting annulment of the Magna Carta. The barons struck back by refusing to give up the city of London unless and until John implemented the Magna Carta. In August 1215, Pope Innocent III issued a “papal bull” (an official letter with a seal “bulla”) declaring the Magna Carta “illegal, unjust, harmful to royal rights and shameful to the English people”, and “null and void of all validity forever”.

In September 1215, civil war broke out between King John and his barons. As usual, John enlisted his army of mercenaries to fight the barons. The barons in turn invited the heir to the French throne to come and become king. The French invaded England in 1216. John died of dysentery during that war.

Henry III succeeded John to the throne at age 9. In November 1216, a revised version of the Magna Carta was issued to regain the loyalty and support of the barons. In 1217, yet another version of the Magna Carta was granted after the expulsion of the French. When Henry reached the age of 18, he issued a significantly revised version which was enrolled on the statute book by King Edward I in 1297.

What is in the Magna Carta of 1215?

The Magna Carta is a document of extraordinary insight, foresight and breadth in terms of its articulation of “English liberties.”

It covers a variety of issues ranging from methods of lodging specific grievances regarding land ownership to the regulation of the justice system, taxes (“scutage” and “socage” [periodic payments for using land], and removal of fish from various rivers and standardization of various weights and measures and so on.

The most notable clauses (Cl.) of the Magna Carta spell out the nature of “English liberties” and resonate to the present day through multitudes of modern constitutions and international human rights treaties and conventions.

In the 1215 Magna Carta, King John agreed to recognize and accept a whole slew of liberties guaranteed to his subjects (barons) that are stunning by the standards of any age. Specifically, he agreed to

• terminate use of the ‘writ of præcipe [order to show cause] by which a free-man may lose his court [right of trial in his own lord’s court]” (Cl. 34).

• prohibit the practice in which a “ bailiff shall put any man to his law, upon his own simple affirmation, without credible witnesses produced for that purpose” (Cl. 38);

• judgment of his peers, or by the laws of the land” (Cl. 39);

The Magna Carta also included un-libertarian terms. It provided that, “no man shall be apprehended or imprisoned on the appeal of a woman, for the death of any other man except her husband” (Cl. 54). A widow could not be “compelled to marry, so long as she wishes to remain without a husband. But she must give security that she will not marry without royal consent (Cl. 8). Six hundred years later, the British philosopher John Stuart Mills wrote, “I consider it presumption in anyone to pretend to decide what women are or are not, can or cannot be, by natural constitution. They have always hitherto been kept, as far as regards spontaneous development, in so unnatural a state, that their nature cannot but have been greatly distorted and disguised…” American women got the constitutional right to vote in 1920. There are still countries in the world in the second decade of the 21st Century where women do not have the right to vote.

The Magna Carta also included a streak of the millennia-old bigotry against Jews. It provided, “If anyone has borrowed anything from the Jews and die before that debt be paid, the debt shall pay no interest so long as his heir shall be under age… And if any one shall die indebted to the Jews, his wife shall have her dower and shall pay nothing of that debt…” (Cls. 10, 11.)

Although the 1215 Magna Carta contained 63 clauses when it was first granted, only a few remain part of English law today. In 1969, the Statute Law (Repeals) Act repealed almost all of the 1225 Magna Carta, except Clauses 1, 9, 29. It has also been superseded by the Human Rights Act of 1998.

The legacy of the Magna Carta as I see it

Learned scholars, lawyers, judges and others will continue to argue about the relevance and significance of the Magna Carta for another 800 years. Did the Magna Carta give all persons in the kingdom or just the “free barons” the right to justice and a fair trial? Did it have any relevance to the unfree peasants (“villeins”) who had to apply to their own lords for justice? Did the Magna Carta guarantee the right to trial by jury? Establish the supremacy of the principle of the rule of law? Institutionalize the due process of law? Did it establish for the very first time a constitutional framework (social contract) between government and citizens? Make practical the idea of individual liberty? Institutionalize the principle of the law of the land to which all (including kings, prime ministers, presidents, congresses, parliaments, etc.,) must submit?

Despite scholarly disagreements, there is substantial consensus that the Magna Carta inspired the framers of the American Constitution (1787) and the drafters of the American Bill of Rights [first ten amendments] (1791) in their quintessential pursuit to limit the arbitrary exercise of governmental power. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights [UDHR] (1948), which has been signed by virtually every country from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe also reflects the text and spirit of the Magna Carta. When Eleanor Roosevelt chaired the committee that drafted the UDHR, she dreamt of a “common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations” with respect to equality, dignity and rights. I agree with her. I do not believe there is Ethiopian “rights”, American “rights”, English “rights”, Chinese “rights”, Egyptian “rights”… I believe there is only human rights.

For me, a dyed-in-the-wool and unapologetic Ethiopian- American constitutional lawyer and scholar, the Magna Carta has enormous symbolic appeal. I understand the Magna Carta as a quintessentially procedural legal document predicated on the twin principles of government accountability and transparency. Those who exercise power shall be held accountable under the supreme law of the land for their actions and omissions by a set of rules and standards. The relationship between the rulers and the ruled must be strictly regulated by a set of clear procedures. No ruler shall have the power to deprive any citizen of life liberty or property without due process of law. I believe the Magna Carta is the first constitutional document in human history to put the brakes on the arbitrary exercise of power and shield individual liberty from the vagaries and capriciousness of those corrupted by power.

William Gladstone who served as British Prime Minister on four separate occasions in the 19th Century, mindful of the Magna Carta observed, “As the British Constitution is the most subtle organism which has proceeded from the womb and the long gestation of progressive history, so the American Constitution is, so far as I can see, the most wonderful work ever struck off at a given time by the brain and purpose of man.” ‘Tis true that imperfect Constitution which turned a blind eye to slavery, is, undoubtedly, a work of extraordinary collective genius.

My view of liberty is a very simple one. I believe liberty predates government. I do not believe government can “grant” rights and freedoms to its citizens. Government, being the collective invention of citizens, exists only to protect the lives, liberties and properties of its citizens.

I have this wacky way of explaining my views on the relationship between government and citizens. I regard government as a watchdog (almost literally) for its masters, the people. (Pardon me if I sound like I am maligning man’s and woman’s best friend with my descriptive metaphor. ) The only function of this watchdog is to protect the lives, liberties and properties of its masters. This watchdog is naturally treacherous and must be watched at all times with eagle eyes and extreme vigilance by its masters. This watchdog has an inbred and ineradicable trait of always turning against its masters unless it is held tightly on a very short chain leash. The constitution is the chain leash on the “government dog”. The shorter the leash, the better and safer it is for the dog’s masters. Thomas Jefferson aptly observed, “When government fears the people, there is liberty. When the people fear the government, there is tyranny.” The government exists to serve the people, not the other way around. The masters of the dog should never fear the dog.

That is why I believe all government officials, leaders, institutions and anyone exercising power should be chained at all times with the “supreme law” of the land, placed under eternal vigilance and held strictly accountable for their actions and omissions. James Madison, one of the foremost framers of the American Constitution wrote, “If men were angels, no government would be necessary.” I would say if governments did not degenerate into demons, men and women could bring out their best and aspire to be angels.

I wholeheartedly agree with John Adams, the second president of the United States who observed, “There is danger from all men [and women]. The only maxim of a free government ought to be to trust no man [or woman] living with power to endanger the public liberty.”

President Dwight D. Eisenhower warned, “The clearest way to show what the rule of law means to us in everyday life is to recall what has happened when there is no rule of law.” Could he have been foretelling the present fate of Africa?

On July 28, 2014, President Obama told a town hall meeting of Young African Leaders, “Regardless of the resources a country possesses, regardless of how talented the people are, if you do not have a basic system of rule of law, of respect for civil rights and human rights, if you do not give people a credible, legitimate way to work through the political process to express their aspirations, if you don’t respect basic freedom of speech and freedom of assembly … it is very rare for a country to succeed.”

Ethiopia needs to succeed as a nation and as a people. Africa needs to succeed as a continent. Today, Ethiopia is in its end stage of becoming a completely failed state. So are many other African countries. I doubt there is a single, not one, African state that would not collapse within days (not weeks) but for Western charity and loans. Contemporary African regimes exist because they are bankrolled by the tax dollars of the Western countries. That is such a bitter pill to swallow!

Over the past five years, cynicism and pessimism have whittled down my hopes and dreams for the rule of law and a peaceful transition to multiparty democracy in Africa. Every day I ask myself, “Is there any hope for Africa?” For Ethiopia? Does Africa’s destiny hang in the balance between the audacity of hope and the rapacity of despair? Is Africa condemned to a future of civil wars, genocides, anarchy, lawlessness and crimes against humanity? Does Africa’s best hope hang on the strings attached to its multilateral loans and aid? Will Africa be buried under a mountain of international debt while predatory foreign investors officiate at its funeral? Is Africa doomed to become the permanent object of charity, sympathy and pity for the rest of the world? Is Africa floating on a turbulent sea of hope or drowning in an ocean of despair? Is there something buried deeply in the African ethos (character), logos (logic of the African mind), pathos (spirit/soul) and bathos (African narrative of the trivial into the sublime) that makes Africans extremely susceptible to the triple deadly cancers of brutality, despotism and corruption? Is Africa the infernal stage of Dante’s “divine comedy”?: “Abandon all hope, you who enter [live] here [in Africa].”

I am sure there will be some among my readership who would question and even criticize me for joyfully celebrating the Magna Carta. After all, it is a document of white people. (I have got to tell the truth!) It is the founding document of the wicked colonial oppressors and the rest of it. The Magna Carta could not possibly have relevance to Black, Brown, Yellow and, yes, Green people. With the exception of Green people, I ask the rest to look at their own constitutions. I would like to ask them where the liberties enshrined in their dusty constitutions originated. I would be glad to know which one of their liberties they are willing to surrender to their governments.

Elie Weisel said, “Just as man cannot live without dreams, he cannot live without hope. If dreams reflect the past, hope summons the future.” So I have chosen to dream about the path of hope – the rule of law administered through a competent independent judiciary to promote freedom, justice and equality– for Ethiopia and the African continent and forswear the path of despair. It is not easy to hope and dream when an entire continent is enveloped and trapped in a long night of dictatorship and oppression. It is in such melancholy state that I find myself reflecting on the words of Henry Francis Lyte:

Swift to its close ebbs out life’s little day;

Earth’s joys grow dim, its glories pass away;

Change and decay in all around I see:

O thou who changest not, abide with me!

I must confess to my readers the great sadness I feel as I conclude this joyful commentary on the Magna Carta.

I am deeply, deeply pained by the irony that I can freely celebrate and cherish an English charter of liberties written 800 years ago which is not even law today, yet I cannot do the same for the Ethiopian Constitution written only twenty years ago to usher a new era of freedom, justice and equality because it is not worth the paper it is written on!

Share this: