Author’s Note: On May 18, 2020, I had an opportunity to make a virtual appearance (in Amharic, begins at minute 36:17- 1:22) before the Ethiopian Constitutional Inquiry Council and share my views on issues related to the postponement of the August 2020 national and regional elections because of the Covid-19 crisis. My purpose in appearing before the Council was to share my knowledge, insights and experience in American constitutional law in addressing the issues before the Council. I am not a stranger to the Ethiopian Constitution. I have written numerous commentaries on it over the past decade and half.

To have an informed conversation about contemporary constitutional issues, it is important for all Ethiopians, especially the so-called elites dabbling and meddling in politics, to have basic familiarity with our constitutional history and the great historical constitutions of the world. With due respect to all African countries, I wish to emphasize that Ethiopia is not a creation of European colonial domination though I am first to acknowledge their machinations and designs to subjugate Ethiopia. Ethiopians have a rich millennia-old civilization and a strong tradition of rule of law and centuries-old system of laws, institutions and norms.

The belief in the supremacy and primacy of the rule of law is so deep in Ethiopia, a proverb says the divine power of the law could stop not only humans but also a flooding river: “Be hig amlak sibal enkwan sew weraj wonz yiqomal.” A critical understanding of our constitutional history will help us gain insight into our current problems, avoid repeating mistakes and chart a clear course for the future.

In successive short commentaries to appear in the coming days, I shall expand on my testimony and answers before the Council and expound on constitutional interpretation. In Part I, I offer an overview based on primary constitutional sources. I invite my readers to examine them to broaden their understanding.

Part I — Understanding constitutionalism and constitutional law

Most people who talk about constitutions in America or Ethiopia have barely read their respective constitutions. Studies show, “Americans know literally nothing about the Constitution.” I suspect that may be equally true for Ethiopians. It is not only the average citizens but also most of the elites who suffer from constitutional literacy or a deficit of constitutional knowledge and understanding in both countries. As a result, extremist elements and the willfully ignorant in America and Ethiopia are often heard blathering uninformed and reckless public pronouncements which subvert constitutional governance into a game of fully loaded Russian roulette.

Generically, a constitution is a legal document that sets out the basic principles and organization of government, specifies the scope and limitations of governmental powers and provides for a scheme of civil liberties. Beyond these basic attributes, there are many different types of constitutions: written and unwritten, republican and monarchical, presidential and parliamentary, federal and unitary, liberal-democratic and socialist and so on. Some constitutions are written in “majestic generalities” and others like ordinary legislation with minute details. Some like the U.S. constitution are short (4,500 words) and others like India’s have exceedingly long (145 thousand words). Some constitutions are interpreted by courts (e.g. judicial review in the U.S.) and a legislative body (e.g. Ethiopia) in others. Some constitutions are driven by ideals of liberty and equality and others by narrow ideology. Most constitutions are secular but there are some theocratic constitutions founded on religious precepts.

In most constitutions, the phrase “supreme law of the land” is used to signify that the constitution is the foundation and ultimate source of legal authority in the society. All government legislation, regulations and rules must conform to the constitution and conflicting laws are deemed invalid. All institutions and leaders are sworn to uphold and defend the constitution. Constitutions are drafted to endure for generations and reflect the consensus of diverse and competing interests in society. They are amended only by extraordinary means because they anchor the foundations of society.

Understanding the constitution of a given society goes beyond textual or semantic analysis of the words. It requires a broader understanding of the society’s history, political struggles and challenges, the diversity of views and perspectives as well as the shared expectations and aspirations of the people.

Constitutional origins

Most constitutions of the world share similar values, aspirations and even substantive textual language. That is because constitution drafting is an eclectic process and draws from diverse historical and contemporary sources.

Most modern constitutions could be traced to the legal systems of classical antiquity. The Constitution of the Roman Republic consisted of informal and unwritten ideas about separation of powers, checks and balances, vetoes, term limits, impeachments. That constitution created legislative chambers and determined rights of citizenship. The Athenian Constitution (Areopagite constitution) consisting of two parts, described the constitutional and legal codes on citizenship, magistrates, and the courts, among other things. Many modern constitutions trace their roots to classical antiquity and modern Western constitutions after the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648 establishing the modern state system.

The Magna Carta (Great Charter) (1215) is a unique constitutional document unlike any other preceding it. It was drafted by the ruled and imposed on the rulers. It was a bold effort to subjugate rulers to the rule of law and aimed to create a binding political contract between subjects and kings. (See my commentary “A Magna Carta for Ethiopia”.) The unwritten Manden Charter (1235) of the great African kingdom of Mali is touted by some as being the first constitutional document to recognize human rights. It aims to promote social peace in diversity, the inviolability of the human being, education, the integrity of the motherland, food security, the abolition of slavery, and freedom of expression and trade. The English “Bill of Rights” (1689), the French “Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen” (1789) and the U.S. Constitution of 1787 with its amendments are inspirational sources for the majority of world constitutions.

Ethiopia’s constitutional history

Most African countries, which gained their independence after 1960, did not have constitutional history before colonialism. Many post-independence African constitutions were drafted with the heavy influence of their former colonial masters. Other African countries which considered themselves “revolutionary” opted to follow the constitutional path of the communist-bloc countries.

Uniquely, Ethiopia has a significant constitutional history dating back to the Middle Ages. The Fetha Nagast (Law of the Kings), compiled around 1240 AD, was Ethiopia’s constitution until a modern one was drafted in 1931. The first part of the Fetha Negast deals with ecclesiastical matters and church hierarchy. The second part covers a variety of secular matters including liberty, slavery, partnership, lease, property rights and other similar things.

The 1931 Constitution replaced the Fetha Negast and represents the first modern constitution of Ethiopia. That constitution deals with succession to the throne, prerogatives of the emperor, rights recognized by the emperor, deliberative chambers of the empire, jurisdiction of courts and functions of ministers.

The 1955 Revised Constitution of Ethiopia consisting of 131 articles was a radical departure from previous conceptions of government and royal authority. It incorporated ideas about separation of powers between three branches of government. However, the king still retained ultimate power including appointment of ministers, senators and judges. Interestingly, Chapter III of that Constitution (“Rights and Duties of the People) could be described as a virtual carbon copy of the American Bill of Rights and other amendments to the U.S. Constitution:

1987 Constitution of Ethiopia, drafted by the military Derg socialist regime, consisted of 119 articles. It created a “National Shengo” (assembly) as the highest organ of state power with members were elected to five-year terms. The president elected by the National Shengo along with ministers appointed by same exercised executive powers. That constitution mimicked constitutions of the communist bloc countries of the time with the ruling party exercising monopoly power in the name of the working people and peasanty.

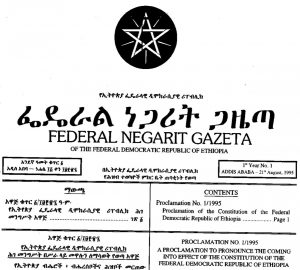

The current 1995 Constitution consisting of 106 articles provides for a parliamentary federal government of nine ethnically-based regions. It creates a dual legislative body of the House of Peoples’ Representatives and the House of Federation and a ceremonial presidency. This constitution has some interesting provisions. Article 13 specifies that these rights and freedoms will be interpreted according to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and other international instruments adopted by Ethiopia. The document further guarantees that all Ethiopian languages will enjoy equal state recognition, although Amharic is specified as the working language of the federal government. Under Chapter III “HUMAN RIGHTS” are listed the following liberties which virtually replicate the American Bill of Rights.

What a constitution is not

In the current discussion and debate over the constitutional authority to postpone the August 2020 national and regional election because of COVID-19, I am amused by the lack of substantive knowledge, shallow understanding of constitutional law and dogmatism of those who proclaim, “After September 30, 2020, there is no government in Ethiopia. It is a free for all. Anyone can establish their own governments.”

The choice is not between a duly established constitutional order and the anarchy of the mob presided over by those thirsty for power. The choice is between a constitutional government that can protect liberty the in terrorem rule of the mob. A wise American jurist writing about American civil liberties warned against converting the constitution into a suicide pact of total anarchy.

Part II- Constitutional interpretation…

Understanding, Interpreting and Applying the Ethiopian Constitution During the Covid-19 Pandemic (Part I- Constitutionalism and Constitutional History))

Posted in Al Mariam's Commentaries By almariam On May 25, 2020Author’s Note: On May 18, 2020, I had an opportunity to make a virtual appearance (in Amharic, begins at minute 36:17- 1:22) before the Ethiopian Constitutional Inquiry Council and share my views on issues related to the postponement of the August 2020 national and regional elections because of the Covid-19 crisis. My purpose in appearing before the Council was to share my knowledge, insights and experience in American constitutional law in addressing the issues before the Council. I am not a stranger to the Ethiopian Constitution. I have written numerous commentaries on it over the past decade and half.

To have an informed conversation about contemporary constitutional issues, it is important for all Ethiopians, especially the so-called elites dabbling and meddling in politics, to have basic familiarity with our constitutional history and the great historical constitutions of the world. With due respect to all African countries, I wish to emphasize that Ethiopia is not a creation of European colonial domination though I am first to acknowledge their machinations and designs to subjugate Ethiopia. Ethiopians have a rich millennia-old civilization and a strong tradition of rule of law and centuries-old system of laws, institutions and norms.

The belief in the supremacy and primacy of the rule of law is so deep in Ethiopia, a proverb says the divine power of the law could stop not only humans but also a flooding river: “Be hig amlak sibal enkwan sew weraj wonz yiqomal.” A critical understanding of our constitutional history will help us gain insight into our current problems, avoid repeating mistakes and chart a clear course for the future.

In successive short commentaries to appear in the coming days, I shall expand on my testimony and answers before the Council and expound on constitutional interpretation. In Part I, I offer an overview based on primary constitutional sources. I invite my readers to examine them to broaden their understanding.

Part I — Understanding constitutionalism and constitutional law

Most people who talk about constitutions in America or Ethiopia have barely read their respective constitutions. Studies show, “Americans know literally nothing about the Constitution.” I suspect that may be equally true for Ethiopians. It is not only the average citizens but also most of the elites who suffer from constitutional literacy or a deficit of constitutional knowledge and understanding in both countries. As a result, extremist elements and the willfully ignorant in America and Ethiopia are often heard blathering uninformed and reckless public pronouncements which subvert constitutional governance into a game of fully loaded Russian roulette.

Generically, a constitution is a legal document that sets out the basic principles and organization of government, specifies the scope and limitations of governmental powers and provides for a scheme of civil liberties. Beyond these basic attributes, there are many different types of constitutions: written and unwritten, republican and monarchical, presidential and parliamentary, federal and unitary, liberal-democratic and socialist and so on. Some constitutions are written in “majestic generalities” and others like ordinary legislation with minute details. Some like the U.S. constitution are short (4,500 words) and others like India’s have exceedingly long (145 thousand words). Some constitutions are interpreted by courts (e.g. judicial review in the U.S.) and a legislative body (e.g. Ethiopia) in others. Some constitutions are driven by ideals of liberty and equality and others by narrow ideology. Most constitutions are secular but there are some theocratic constitutions founded on religious precepts.

In most constitutions, the phrase “supreme law of the land” is used to signify that the constitution is the foundation and ultimate source of legal authority in the society. All government legislation, regulations and rules must conform to the constitution and conflicting laws are deemed invalid. All institutions and leaders are sworn to uphold and defend the constitution. Constitutions are drafted to endure for generations and reflect the consensus of diverse and competing interests in society. They are amended only by extraordinary means because they anchor the foundations of society.

Understanding the constitution of a given society goes beyond textual or semantic analysis of the words. It requires a broader understanding of the society’s history, political struggles and challenges, the diversity of views and perspectives as well as the shared expectations and aspirations of the people.

Constitutional origins

Most constitutions of the world share similar values, aspirations and even substantive textual language. That is because constitution drafting is an eclectic process and draws from diverse historical and contemporary sources.

Most modern constitutions could be traced to the legal systems of classical antiquity. The Constitution of the Roman Republic consisted of informal and unwritten ideas about separation of powers, checks and balances, vetoes, term limits, impeachments. That constitution created legislative chambers and determined rights of citizenship. The Athenian Constitution (Areopagite constitution) consisting of two parts, described the constitutional and legal codes on citizenship, magistrates, and the courts, among other things. Many modern constitutions trace their roots to classical antiquity and modern Western constitutions after the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648 establishing the modern state system.

The Magna Carta (Great Charter) (1215) is a unique constitutional document unlike any other preceding it. It was drafted by the ruled and imposed on the rulers. It was a bold effort to subjugate rulers to the rule of law and aimed to create a binding political contract between subjects and kings. (See my commentary “A Magna Carta for Ethiopia”.) The unwritten Manden Charter (1235) of the great African kingdom of Mali is touted by some as being the first constitutional document to recognize human rights. It aims to promote social peace in diversity, the inviolability of the human being, education, the integrity of the motherland, food security, the abolition of slavery, and freedom of expression and trade. The English “Bill of Rights” (1689), the French “Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen” (1789) and the U.S. Constitution of 1787 with its amendments are inspirational sources for the majority of world constitutions.

Ethiopia’s constitutional history

Most African countries, which gained their independence after 1960, did not have constitutional history before colonialism. Many post-independence African constitutions were drafted with the heavy influence of their former colonial masters. Other African countries which considered themselves “revolutionary” opted to follow the constitutional path of the communist-bloc countries.

Uniquely, Ethiopia has a significant constitutional history dating back to the Middle Ages. The Fetha Nagast (Law of the Kings), compiled around 1240 AD, was Ethiopia’s constitution until a modern one was drafted in 1931. The first part of the Fetha Negast deals with ecclesiastical matters and church hierarchy. The second part covers a variety of secular matters including liberty, slavery, partnership, lease, property rights and other similar things.

The 1931 Constitution replaced the Fetha Negast and represents the first modern constitution of Ethiopia. That constitution deals with succession to the throne, prerogatives of the emperor, rights recognized by the emperor, deliberative chambers of the empire, jurisdiction of courts and functions of ministers.

The 1955 Revised Constitution of Ethiopia consisting of 131 articles was a radical departure from previous conceptions of government and royal authority. It incorporated ideas about separation of powers between three branches of government. However, the king still retained ultimate power including appointment of ministers, senators and judges. Interestingly, Chapter III of that Constitution (“Rights and Duties of the People) could be described as a virtual carbon copy of the American Bill of Rights and other amendments to the U.S. Constitution:

1987 Constitution of Ethiopia, drafted by the military Derg socialist regime, consisted of 119 articles. It created a “National Shengo” (assembly) as the highest organ of state power with members were elected to five-year terms. The president elected by the National Shengo along with ministers appointed by same exercised executive powers. That constitution mimicked constitutions of the communist bloc countries of the time with the ruling party exercising monopoly power in the name of the working people and peasanty.

The current 1995 Constitution consisting of 106 articles provides for a parliamentary federal government of nine ethnically-based regions. It creates a dual legislative body of the House of Peoples’ Representatives and the House of Federation and a ceremonial presidency. This constitution has some interesting provisions. Article 13 specifies that these rights and freedoms will be interpreted according to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and other international instruments adopted by Ethiopia. The document further guarantees that all Ethiopian languages will enjoy equal state recognition, although Amharic is specified as the working language of the federal government. Under Chapter III “HUMAN RIGHTS” are listed the following liberties which virtually replicate the American Bill of Rights.

What a constitution is not

In the current discussion and debate over the constitutional authority to postpone the August 2020 national and regional election because of COVID-19, I am amused by the lack of substantive knowledge, shallow understanding of constitutional law and dogmatism of those who proclaim, “After September 30, 2020, there is no government in Ethiopia. It is a free for all. Anyone can establish their own governments.”

The choice is not between a duly established constitutional order and the anarchy of the mob presided over by those thirsty for power. The choice is between a constitutional government that can protect liberty the in terrorem rule of the mob. A wise American jurist writing about American civil liberties warned against converting the constitution into a suicide pact of total anarchy.

Part II- Constitutional interpretation…

Share this:

Related Posts